Japonisme: A Passion for Japan

Japonisme: A Passion for Japan

French author Philippe Burty (1830–90) coined the term Japonisme in 1872 to describe the new fervor for all things Japanese, following Japan’s opening to international trade after a prolonged period of isolation from the West. The increased visibility of Japanese art and design overseas profoundly affected European and North American audiences as ceramics, ukiyo-e woodblock prints, metalwork, lacquerware, fans, and textiles flooded Western markets. Japonisme permeated fine and decorative arts, interior design, and graphic arts. Artists such as Vincent van Gogh (1853–90) and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) were deeply inspired by Japanese art. American silver manufacturers including Tiffany & Company and the Gorham Manufacturing Company were determined to create metalwork as fine as Japan’s. English potteries took heed of Japanese designs to create a plethora of new patterns.

The first world’s fair to feature Japanese art took place in London in 1862. Japan’s official participation in an international exposition occurred in Paris in 1867, followed by Vienna in 1873, and Philadelphia in 1876. These expositions exposed millions of people to Japanese art, craft, design, and architecture. Japanese art dealers, such as Hiromichi Shugio (1853–1927) in New York, Bunkio Matsuki (1867–1940) in Boston, and Tadamasa Hayashi (1853–1906) in Paris, helped introduce Japanese arts to American and European clienteles. Prominent English designer Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) traveled to Japan in 1876, later publishing his influential book Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufacturers (1882). Art critics and home journals of the era regularly published articles addressing how to decorate one’s home in a Japanese-inspired style. Collectors eagerly purchased authentic Japanese goods and Western interpretations of them.

The first world’s fair to feature Japanese art took place in London in 1862. Japan’s official participation in an international exposition occurred in Paris in 1867, followed by Vienna in 1873, and Philadelphia in 1876. These expositions exposed millions of people to Japanese art, craft, design, and architecture. Japanese art dealers, such as Hiromichi Shugio (1853–1927) in New York, Bunkio Matsuki (1867–1940) in Boston, and Tadamasa Hayashi (1853–1906) in Paris, helped introduce Japanese arts to American and European clienteles. Prominent English designer Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) traveled to Japan in 1876, later publishing his influential book Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufacturers (1882). Art critics and home journals of the era regularly published articles addressing how to decorate one’s home in a Japanese-inspired style. Collectors eagerly purchased authentic Japanese goods and Western interpretations of them.

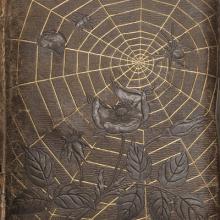

Western decorative arts manufacturers adopted Japanese motifs, such as asymmetry and imagery inspired by the natural world, including insects—from butterflies and dragonflies to black flies. The spider and its web now adorned everything from silver plate to wallpaper and framed portraits. Birds and sea creatures, such as cranes, owls, and carp were introduced as decorative motifs. Western artists looked at familiar trees and changing foliage in a new light—from cherry blossoms to autumn maple leaves, and bamboo. A variety of flowers found new meaning, including peonies, wisteria, and irises. The intriguing decorative lexicon of Japan also included ocean waves, clouds, lightning bolts, and cracked ice.

This exhibition features American and European decorative arts from the 1870s–90s, when Japonisme reached its peak in popularity. Rather than directly copying, Western artists drew freely from Japanese ornament reinterpreting objects ranging from sterling silver flatware and holloware to colorful ceramic plates and vessels. Designs on Japanesque lamps, fire screens, and book covers are among the many everyday items that also feature imaginative imagery, all of which reflect an early and remarkable example of international cultural exchange between Japan and the West.

[image]

Dragon vase c. 1880s

Royal Worcester

Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England

earthenware, glaze

Courtesy of Brian D. Coleman

L2022.0404.007

© 2022 by San Francisco Airport Commission. All rights reserved.