International Terminal

Block 0003 1987

various makers

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

L2025.0301.001

Early AIDS Activism

HIV/AIDS was shrouded in mystery during the early 1980s at the onset of the epidemic. Initially classified as gay-related immune deficiency (GRID) by medical professionals, the first cases in the United States appeared primarily in gay men from communities in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Symptoms often began with purple lesions attributed to Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), a rare skin cancer that could progress into pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) or another fatal illness. NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt co-founder Cleve Jones recalled, “By 1984, San Francisco had become ‘Ground Zero of the Plague’ as Time magazine famously called it. People died fast then. One day you would see someone who looked fine. A month later he looked bad. Two weeks later you’d see his name in the obituaries.”

In 1981, Bobbi Campbell (1952–84), the sixteenth person diagnosed with KS in San Francisco, proclaimed in The Sentinel, “I have ‘gay cancer’…I’m writing because I have a determination to live. You do too—don’t you?” Campbell, an activist and registered nurse, refused to be labeled a victim. He fought alongside fellow activists to develop self-empowerment and a collective voice among people living with the disease, co-founding the National Association of People with AIDS in 1983. That August, Campbell and his partner Bobby Hilliard appeared on the cover of Newsweek, titled “Gay America: Sex, Politics, and the Impact of AIDS”—introducing mainstream America to the epidemic. The panel on block 0003 that bears Campbell’s name was made by activist and artist Gilbert Baker (1951–2017), co-creator of the Rainbow Flag. This block was one of five hung from former mayor Dianne Feinstein’s (1933–2023) office during the San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Day Parade and Celebration in June 1987, the first public display of the Quilt.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt on the Mayor’s Balcony,

San Francisco City Hall 1987

Marc Geller

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

R2025.0301.012.20

Block 2908 1993

various makers

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

L2025.0301.002

The AIDS Memorial Quilt Grows

The first large-scale display of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt was scheduled to correspond with the 1987 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. To make their October deadline, volunteers worked quickly with paint, permanent marker, felt letters, and names and designs cut from scraps of fabric. The Quilt grew exponentially as awareness of the NAMES Project spread and panels were shipped to San Francisco by mail. One maker from Maryland used buttons to spell her mother’s name, Margaret Janick Emmitt (1931–85), and honor her eclectic personality. Another maker from Atlanta used handprints stamped from paint in remembrance of Lee Charles Leathers (c. 1958–92), a close friend he had met through an HIV/AIDS support group.

By 1989, more than fifty-nine thousand Americans from all walks of life had died of AIDS-related illnesses. Yet popular stigmas still attributed HIV/AIDS to the LGBTQ community and to intravenous drug users. Tennis star, author, and human rights activist Arthur Robert Ashe, Jr. (1943–93) was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988. Five years earlier, he had received a blood transfusion during a heart operation that was likely contaminated with the HIV virus. The first Black male athlete to win the US Open, the Australian Open, and the Wimbledon singles championship, he created the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS after publicly revealing his diagnosis in 1992, advocating for education, health care reform, and access to treatment.

![“The Cordova Curve” [Inaugural AIDS Memorial Quilt display on the National Mall] 1987 Marc Geller Washington, DC Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial](/sites/default/files/inline-images/02a-aids-memorial-quilt-sfom.jpg)

“The Cordova Curve” [Inaugural AIDS Memorial Quilt display on the National Mall] 1987

Marc Geller

Washington, DC

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

R2025.0301.012.03

Block 3315 1994

various makers

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

L2025.0301.003

AIDS Activism and the Media

In 1982, activist, author, and singer-songwriter Michael Callen (1955–93) co-wrote “We Know Who We Are” for the New York Native with fellow activist and author Richard Berkowitz (b. 1955), controversially warning gay men about research that linked sexual activity and AIDS. The following year, Callen and Berkowitz authored How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach—now considered the first guide to safe sex. At a time when many people living with AIDS were abandoned by friends and family due to public hysteria that surrounded the epidemic, Callen was bravely outspoken about his diagnosis and work. Shortly before passing, Callen performed his song Love Don’t Need a Reason, an AIDS rights movement anthem, at the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation.

Randy Shilts (1951–94) was an investigative journalist who covered the AIDS epidemic as it unfolded from the start. The first openly gay reporter hired by the San Francisco Chronicle, he focused on local and national issues that surrounded HIV/AIDS with an unrelenting style and personal dedication that invited backlash. Shilts’ book, And the Band Played On, was acclaimed for humanizing people living with AIDS. Yet it was surrounded by controversy, most notably in his misidentification of Gaëtan Dugas (1953–84) as “Patient Zero.” Shilts strove to eradicate homophobia through journalism and stated, “I feel that prejudice in our society is born less out of malice than out of ignorance, and that if you just inform people…you can do more to erase prejudice than any other kind of action.”

The AIDS Memorial Quilt on the Ellipse 1988

Marcel Miranda III (1956–2009)

Washington, DC

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

R2025.0301.012.06

Block 5788 2008

various makers

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

L2025.0301.013

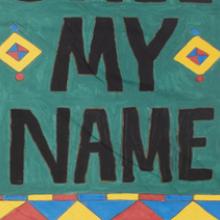

Quilting and “Call My Name”

The AIDS Memorial Quilt is rooted in the American tradition of quilting, bringing people together to exchange conversation as they sew. When he envisioned the Quilt in 1985, Cleve Jones (b. 1954) stated, “I imagined families sharing stories of their loved ones as they cut and sewed the fabric. It could be therapy, I hoped, for a community that was increasingly paralyzed by grief and rage and powerlessness.” Panel makers have attested to the Quilt’s emotional healing through the communal and familial support they receive. To memorialize the lives of those lost to AIDS, makers often sew paintings, clothing, photographs, letters, and other personal items directly onto panels. To capture their own voices, many people living with HIV/AIDS make or assist with their panels. When necessary, these very personal memorials are completed by friends and family.

In 2003, the NAMES Project initiated “Call My Name” to reflect the changing dynamic of the epidemic and its disproportionate impact on people of color. Through focused panel making and displays, “Call My Name” raises awareness of the negative effects that stigma and prejudice have on prevention and treatment. In 2004, AIDS-related illnesses were the leading cause of death for African American women between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-four. While modern medicine has drastically slowed death rates, in 2021, Black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States faced a one-in-three lifetime risk of acquiring HIV. The following year, Latinx gay, bisexual, and other MSM accounted for more new HIV infections than in any other ethnic group in the country. That summer, the National AIDS Memorial and Southern AIDS Coalition launched “Change the Pattern,” a tour of Quilt panels that honored Black and Brown lives.

For information on how to make and submit a panel to the AIDS Memorial Quilt, please visit aidsmemorial.org

Pete Martinez sewing the Quilt 1991

Theresa DiMenno

San Francisco

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

R2025.0301.012.16

Block 5961 2013

various makers

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

L2025.0301.005

Quilt Activism and ACT UP

In 1986, a National Academy of Sciences report characterized the federal government’s response to the AIDS crisis as “woefully inadequate.” The report urged former president Ronald Reagan (1911–2004), who had largely ignored the epidemic, to “take a strong leadership role in the effort against AIDS and HIV.” Gert McMullin (b. 1955), an original NAMES Project volunteer and the current caretaker of the Quilt at the National AIDS Memorial, explained one of their founding objectives: to move activism beyond statistics and “lay our dead down in front of our nation’s capital for all the world to see.” Each Quilt panel measures three-by-six feet—a size envisioned to approximate a human grave—to visually and powerfully illustrate the personal dimension of those lost to AIDS.

The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) is one of the most influential activist groups represented in the Quilt. Often seen demonstrating beneath banners and signs emblazoned with the pink triangle and “Silence=Death” call to action, ACT UP members employ confrontational tactics and direct action in their efforts to end the AIDS epidemic. On October 11, 1988, fifteen-hundred ACT UP members descended on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) headquarters in Rockville, Maryland, to “Seize Control of the FDA,” their first national demonstration. Within a year, the FDA agreed to speed development of AIDS medications and had modified clinical trial methods, making potentially lifesaving, experimental drugs available to people living with HIV/AIDS.

Gert McMullin sewing at the NAMES Project workshop 1996

San Francisco

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

R2025.0301.012.15

Block 6022 2023

various makers

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

L2025.0301.006

Activism and Art

AIDS activist Roger Gail Lyon (1948–84) was one of the first San Franciscans to die from an AIDS-related illness. Just one year prior, Lyon testified before Congress on funding for AIDS research: “I came here today with the hope that this administration would do everything possible, make every resource available… this is not a political issue. This is a health issue. This is not a gay issue. This is a human issue…I came here today in the hope that my epitaph would not read that I died of red tape.” Discrimination against the LGBTQ community and people living with HIV/AIDS stalled medical research and the epidemic spread with little hope in sight. Today, advances in medicine allow people who have access to treatment to effectively manage the disease. However, HIV/AIDS continues to devastate communities with inadequate resources.

Artist, writer, and activist David Wojnarowicz (1954–92) exhibited his first paintings in New York’s East Village in 1982; two years later, he was shown in forty international exhibitions. After his partner, photographer Peter Hujar (1934–87), died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987, Wojnarowicz increasingly focused on the epidemic through multiple media, including a Quilt panel for Hujar. In 1988, Wojnarowicz was diagnosed with AIDS and joined the activist group ACT UP with his partner, social worker Tom Rauffenbart (1945–2019). Inspired by Wojnarowicz, ACT UP led the “Ashes Action” in 1992, throwing the cremated remains of friends lost to AIDS onto the White House lawn. During the second “Ashes Action” in 1996, Rauffenbart cast Wojnarowicz’s remains over the president’s fence alongside demonstrators with the ashes of others.

Two mourners at the AIDS Memorial Quilt 1988

Richard Lord

Washington, DC

Courtesy of the National AIDS Memorial

R2025.0301.012.05