International Terminal

Ancient intersection of the Via Appia and Via Ardentina viewed at the second milestone outside the Porta Capena 1756

Le Antichità Romane II (The Antiquities of Rome, Vol. 2), Plate II

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano Veneto 1720 – 1778 Rome)

etching on laid paper

15.75 x 25 in

L2016.2101.010

![[detail] Ancient intersection of the Via Appia and Via Ardentina viewed at the second milestone outside the Porta Capena 1756 Le Antichità Romane II (The Antiquities of Rome, Vol. 2), Plate II Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano 1720 – 1778 Rome) etching on laid paper 15.75 x 25 in L2016.2101.010 detail Ancient intersection of the Via Appia and Via Ardentina viewed at the second milestone outside the Porta Capena 1756 Le Antichità Romane II (The Antiquities of Rome, Vol. 2), Plate II Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano 1720 – 1778 Rome) etching on laid paper 15.75 x 25 in L2016.2101.010](/sites/default/files/inline-images/01_detail_roads_to_rome.jpg) After nearly a decade of careful study, Giovanni Battista Piranesi produced Le Antichità Romane (1756)—a four-volume work of 250 plates documenting and championing Rome’s architectural heritage. While recent excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum inspired widespread interest in ancient architecture, many of Rome’s great ruins had not yet been properly excavated, with many still plundered for cheap building materials.

After nearly a decade of careful study, Giovanni Battista Piranesi produced Le Antichità Romane (1756)—a four-volume work of 250 plates documenting and championing Rome’s architectural heritage. While recent excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum inspired widespread interest in ancient architecture, many of Rome’s great ruins had not yet been properly excavated, with many still plundered for cheap building materials.

In this imaginary view—veduta ideata—Piranesi fills the roadside with a wild assortment of gravestones, busts, tombs, and mausoleums, variously decorated with Latin inscriptions and Egyptian hieroglyphics, and sprouting with vegetation. Piranesi includes milestone markers for both the Via Appia (center of composition) and Via Ardentina (in shadows, at right of composition), with the two historic roads converging near a pile of ruined sculpture in the foreground at right. While the monuments are out of scale with one another, they dwarf the people occupying the roadway, communicating the magnitude and enduring grandeur of ancient Rome to its mid-18th century visitors.

Colosseum and Arch of Constantine c. 1650

Viviano Codazzi (Bergamo 1606 – 1670 Rome)

figures by Michelangelo Cerquozzi (Rome, 1602 – 1660)

oil on canvas

56 x 77 in

L2016.2101.025

![[detail] Colosseum and Arch of Constantine c. 1650 Viviano Codazzi (Bergamo 1606 – 1670 Rome) figures by Michelangelo Cerquozzi (Rome, 1602 – 1660) oil on canvas 56 x 77 in L2016.2101.025 detail Colosseum and Arch of Constantine c. 1650 Viviano Codazzi (Bergamo 1606 – 1670 Rome) figures by Michelangelo Cerquozzi (Rome, 1602 – 1660) oil on canvas 56 x 77 in L2016.2101.025](/sites/default/files/inline-images/02_detail_roads_to_rome.jpg) Born in Bergamo in 1606, painter Viviano Codazzi reached Naples by the 1620s, where he demonstrated remarkable skill with quadratura—architectural perspective. Despite working in Naples until moving to Rome in 1647, Codazzi did not adopt the flamboyant mannerisms characteristic of Neapolitan, high-Baroque painting. Instead, Codazzi pursued an illusionistic realism, employing his skills of perspective, architectural rendering, and strong lighting to create a picture of a very real place, even if the viewpoint was impossible and the details inaccurate.

Born in Bergamo in 1606, painter Viviano Codazzi reached Naples by the 1620s, where he demonstrated remarkable skill with quadratura—architectural perspective. Despite working in Naples until moving to Rome in 1647, Codazzi did not adopt the flamboyant mannerisms characteristic of Neapolitan, high-Baroque painting. Instead, Codazzi pursued an illusionistic realism, employing his skills of perspective, architectural rendering, and strong lighting to create a picture of a very real place, even if the viewpoint was impossible and the details inaccurate.

Codazzi’s body of work largely consists of medium-size architectural paintings. This large, impressive picture of the Colosseum is characteristic of the painter’s mature work of the 1650s. The highly realized figure group is by Michelangelo Cerquozzi (1602–60) of the Roman Bamboccianti painters, with whom Codazzi collaborated on many pictures. Luciano Ascanio (1621–1706), whose work is also on exhibition, was among Codazzi’s most dedicated students, and Codazzi’s son, Niccolò, was also an accomplished painter

Arch of Titus c. 1830

maker unknown

rosso antico, nero antico

14.5 x 10.5 x 4.75 in

L2016.2101.057

![[detail] Arch of Titus c. 1830 maker unknown rosso antico, nero antico 14.5 x 10.5 x 4.75 in L2016.2101.057 detail Arch of Titus c. 1830 maker unknown rosso antico, nero antico 14.5 x 10.5 x 4.75 in L2016.2101.057](/sites/default/files/inline-images/03_detail_roads_to_rome.jpg) This unusual, highly realized model of the Arch of Titus was carved shortly after the monument’s restoration in 1823 by architect Giuseppe Valadier (1762–1839), who used contrasting colors of marbles to differentiate between original and restored portions. Valadier incorporated smooth columns farthest from the opening in contrast with the monument’s original fluted columns. One side features the original dedication to Titus in Roman square capitals, while opposite, Valadier’s work was referenced in a new inscription: (THIS) MONUMENT, REMARKABLE IN TERMS OF BOTH RELIGION AND ART; HAD WEAKENED FROM AGE; PIUS THE SEVENTH, SUPREME PONTIFF; BY NEW WORKS ON THE MODEL OF THE ANCIENT EXEMPLAR; ORDERED IT REINFORCED AND PRESERVED; IN THE 24TH YEAR OF HIS SACRED RULERSHIP.

This unusual, highly realized model of the Arch of Titus was carved shortly after the monument’s restoration in 1823 by architect Giuseppe Valadier (1762–1839), who used contrasting colors of marbles to differentiate between original and restored portions. Valadier incorporated smooth columns farthest from the opening in contrast with the monument’s original fluted columns. One side features the original dedication to Titus in Roman square capitals, while opposite, Valadier’s work was referenced in a new inscription: (THIS) MONUMENT, REMARKABLE IN TERMS OF BOTH RELIGION AND ART; HAD WEAKENED FROM AGE; PIUS THE SEVENTH, SUPREME PONTIFF; BY NEW WORKS ON THE MODEL OF THE ANCIENT EXEMPLAR; ORDERED IT REINFORCED AND PRESERVED; IN THE 24TH YEAR OF HIS SACRED RULERSHIP.

This model was crafted from nero antico originally quarried on Greece’s Peloponnese peninsula, then a Roman colony, in the time of Augustus in the early 1st century CE. Shipped to Rome, the stone formed part of the city’s architectural fabric. Serial sackings led to the destruction of many of the city’s monuments. Early in the 19th century, a piece of that rubble was re-worked into this architectural souvenir.

Varia Marci Ricci Pictoris Praestantissimi Experimenti; No. 9 and No. 10 from set of twenty plates 1730

Marco Ricci (Belluno 1676 – 1729 Venice)

etchings on laid paper

16.75 x 12 in

L2016.2101.013, .016

Venetian painter Marco Ricci’s posthumously printed set of twenty etched landscapes—Varia Marci Ricci Pictoris Praestantissimi Experimenti—was introduced in 1730, ten years prior to the arrival of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–78) to Rome. Piranesi was certainly aware of Ricci’s series before embarking on his own career as an etcher of Roman views. This pair of etchings, like Ricci’s most significant paintings, depicts ruins in particularly elegant and picturesque compositions. The scenes unfold on both sides of a great arch set to the middle distance. The figures inhabiting the pictures appear at ease with the tumbled-down antiquity that surrounds them.

Venetian painter Marco Ricci’s posthumously printed set of twenty etched landscapes—Varia Marci Ricci Pictoris Praestantissimi Experimenti—was introduced in 1730, ten years prior to the arrival of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–78) to Rome. Piranesi was certainly aware of Ricci’s series before embarking on his own career as an etcher of Roman views. This pair of etchings, like Ricci’s most significant paintings, depicts ruins in particularly elegant and picturesque compositions. The scenes unfold on both sides of a great arch set to the middle distance. The figures inhabiting the pictures appear at ease with the tumbled-down antiquity that surrounds them.

For all the gentility and elegance of these compositions, it may come as a surprise that their creator was a murderer and a suicide victim. Early in his life, Ricci killed a gondolier while fleeing Venice just ahead of the law. At life’s end, he determined to die like a knight, refusing sustenance, laid out in the costume of a cavalieri, with a rapier by his side.

Temple of Castor and Pollux c. 1860

maker unknown

brecciated giallo antico, nero antico

30 x 14 x 5.5 in

L2016.2101.053

Temple of Vespasian and Titus c. 1860

maker unknown

brecciated giallo antico, nero antico

29.5 x 10 x 10 in

L2016.2101.048

The Temple of Castor and Pollux in Rome’s Forum was constructed in 484 BCE where, in the previous decade, the twin sons of Jupiter and Leda were said to have announced their victory after aiding the Romans in the legendary Battle of Lake Regillus. During the Republican period (approximately 500 BCE to 30 BCE), the temple was the site of an annual cavalry parade commemorating the victory, and it was also used as a secret meeting place for the Roman Senate. It later housed the office for weights and measures and served as the Treasury for Imperial Rome.

The Temple of Castor and Pollux in Rome’s Forum was constructed in 484 BCE where, in the previous decade, the twin sons of Jupiter and Leda were said to have announced their victory after aiding the Romans in the legendary Battle of Lake Regillus. During the Republican period (approximately 500 BCE to 30 BCE), the temple was the site of an annual cavalry parade commemorating the victory, and it was also used as a secret meeting place for the Roman Senate. It later housed the office for weights and measures and served as the Treasury for Imperial Rome.

The temple originally included eight columns on its short sides and eleven on its long sides, with an interior chamber paved with mosaics. It stood fifty feet tall with a twelve-foot entablature. The temple fell into ruin in the 4th century, and by the 15th century, only the present three columns remained.

Miniatures of both the Temple of Vespasian and Titus and the Temple of Castor and Pollux were popular with visitors to these familiar ruins in Rome’s Forum. The earliest versions date to the first part of the 19th century, when archaeological excavations of these temples revealed much of their current forms. Thus, while we consider these places as ancient, it was their novelty that spurred the production of souvenirs.

Replicas fashioned in this period are typically smaller, and less exactingly turned out than those carved earlier. The stone for these models was quarried in western Tunisia at the height of the Roman Empire two thousand years ago and incorporated into the city’s ancient architecture. After Rome’s fall, it undoubtedly formed part of the city’s rubble and was eventually scavenged by an opportunistic scarpellino—stone carver.

Claude-Joseph Vernet, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, and Charles-Louis Clérisseau at the Great Baths, Hadrian’s Villa c. 1752

Claude-Joseph Vernet (Avignon 1714 – 1789 Paris)

brown ink, wash and body color on laid paper

9.5 x 13.5 in

L2016.2101.037

Giovanni Piranesi’s 1799 biography provides an account of the master printmaker’s visit a half-century earlier to Hadrian’s Villa. Two French painters joined him—Charles-Louis Clérisseau (1721–1820), then a young man fresh to Rome, and Claude-Joseph Vernet, a bit older, and on the verge of being recalled to Paris by King Louis XV for a project that would distinguish him as one of the great landscape painters of the 18th century.

Giovanni Piranesi’s 1799 biography provides an account of the master printmaker’s visit a half-century earlier to Hadrian’s Villa. Two French painters joined him—Charles-Louis Clérisseau (1721–1820), then a young man fresh to Rome, and Claude-Joseph Vernet, a bit older, and on the verge of being recalled to Paris by King Louis XV for a project that would distinguish him as one of the great landscape painters of the 18th century.

Vernet’s drawing depicts the three men gathered within an arched niche. One stands and the other two are seated, engrossed in sketching the scene before them. On the ruin’s roof are two more men. Perhaps they accompanied the artists. Perhaps they are figments, provided by the artist for scale or compositional balance. A light fold down the center of this sheet is revealed by a thin line of ink gathered to the bottom of the crease, indicating that Vernet, more than 250 years ago, folded this lovely ink drawing a few minutes before it was fully dry. Perhaps it was time for this band of artists to be on their way.

Arch of Constantine c. 1820

Wilhelm Hopfgarten (Berlin 1779 – 1860 Rome) and Benjamin Ludwig Jollage (Berlin 1781 – 1837 Rome)

gilded bronze, Carrara marble base

13.5 x 10.75 x 6.25 in

L2016.2101.003

The Arch of Constantine spans the route taken by triumphant emperors returning from battle to Rome. The monument commemorates the victory by Constantine I over rival Maxentius in 312 CE after God allegedly promised the emperor’s soldiers victory if the sign of the cross was made on their shields. Although somewhat vague, and perhaps purposefully so, the monument’s inscription celebrating “blessed Augustus…inspired by the divine” may be the first public reference to Constantine’s conversion to Christianity.

The Arch of Constantine spans the route taken by triumphant emperors returning from battle to Rome. The monument commemorates the victory by Constantine I over rival Maxentius in 312 CE after God allegedly promised the emperor’s soldiers victory if the sign of the cross was made on their shields. Although somewhat vague, and perhaps purposefully so, the monument’s inscription celebrating “blessed Augustus…inspired by the divine” may be the first public reference to Constantine’s conversion to Christianity.

The Arch of Constantine was constructed with spolia—the remains of earlier buildings. Eight statues depict captured enemies and were probably taken from the Forum of Trajan. Many of the friezes originally decorated monuments to emperors Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius. The monument’s detached columns, three archways, and an inscribed panel above the central archway were modeled on the Arch of Septimius Severus, erected a century earlier in Rome’s Forum.

By the 1820s, the Roman bronze foundry of Prussian émigrés Wilhelm Hopfgarten and Benjamin Ludwig Jollage was a well-known source for souvenir architectural models of Rome’s ancient monuments. Their detailed design and high level of execution set the standard for this sort of work in Rome until the mid-19th century. While most of the firm’s models were made as mementos for Grand Tourists, others were made for the Papacy and as gifts for foreign dignitaries.

The Arch of Constantine was one of the firm’s earliest subjects. As with other monuments from ancient Rome, Hopfgarten and Jollage chose to portray the Arch of Constantine not as it existed circa 1820, but as it was originally designed. Thus, their model is topped by monumental statues of a four-horse chariot, its driver (Constantine, presumably), and accompanying riders of the Imperial Cavalry. While scholars debate the precise rendition of the sculptural group, these figures certainly occupied the Arch’s roof until pulled down during one of Rome’s serial sackings.

Capriccio View of Ancient Roman Monuments c. 1755

Giovanni Paolo Panini (Piacenza 1691 – 1765 Rome)

oil on canvas

31 x 43 in

L2016.2101.085

By the mid-18th century, Giovanni Paolo Panini, Rome’s most successful painter of the city’s ancient architectural ruins, oversaw a thriving workshop of artists, whose production of the master’s pictures was prolific. It appears Panini was more or less directly involved in each picture; and almost certainly sketched the broad outline of canvases prior to his painters setting to work. According to art historian Ferdinando Arisi (1920–2013), one of the foremost authorities on Panini, the present painting is wholly by Panini.

By the mid-18th century, Giovanni Paolo Panini, Rome’s most successful painter of the city’s ancient architectural ruins, oversaw a thriving workshop of artists, whose production of the master’s pictures was prolific. It appears Panini was more or less directly involved in each picture; and almost certainly sketched the broad outline of canvases prior to his painters setting to work. According to art historian Ferdinando Arisi (1920–2013), one of the foremost authorities on Panini, the present painting is wholly by Panini.

This highly realized capriccio view includes a variety of antique monuments, albeit in a completely imaginary and picturesque juxtaposition to each other. From left to right are the Porticus Octaviae, Farnese Hercules, Colosseum, Pyramid of Caius Cestius, Arch of Constantine, and Trajan’s Column. Interestingly, Panini and his studio produced another half dozen paintings of this view. Each canvas is a different dimension and proportion with slightly different details—more figures or fewer—and one even omits Trajan’s Column.

Four Rivers Fountain c. 1675

unidentified Roman sculptor

cast bronze

52 x 26 x 23 in

L2016.2101.059

It was spring, 1647, in Rome, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), Europe’s greatest Baroque architect and sculptor, was on a losing streak. Commissioned in 1638 by his patron Pope Urban VIII to design a pair of flanking bell towers for Saint Peter’s Basilica, the work had structurally failed and was removed after 1642. In 1644, Urban VIII died, and the new Pope, Innocent X, sought out new talent for the impressive works he had in mind.

It was spring, 1647, in Rome, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), Europe’s greatest Baroque architect and sculptor, was on a losing streak. Commissioned in 1638 by his patron Pope Urban VIII to design a pair of flanking bell towers for Saint Peter’s Basilica, the work had structurally failed and was removed after 1642. In 1644, Urban VIII died, and the new Pope, Innocent X, sought out new talent for the impressive works he had in mind.

Chief among these was a new fountain planned for Rome’s Piazza Navona. Pope Innocent X asked several leading architects for proposals, but not Bernini, and appeared to have accepted a plan by Francesco Borromini (1599–1667), Bernini’s fiercest rival. Accounts have this as a low point for the artist. Yet, through the connivance of the Pope’s intimates, it was arranged for Bernini to make a silver model of his proposal and have it placed along the Pope’s path as he made his way to dinner. Seeing it, the Pope understood the subversion afoot, yet famously warned “… he who desires not to use Bernini’s designs, must take care not to see them.”

The Four Rivers Fountain, unveiled June 12, 1651, features four colossal carved figures personifying the world’s four great then-known rivers—the Ganges, Danube, Nile, and Rio de la Plata. These are perched on carved travertine rockwork, which supports the Obelisk of Domitian, brought from Egypt in the 1st century CE. The assemblage, animated by rushing, churning, roaring waterworks, is one of the great fountains of the world.

In addition to that silver model now lost, which won him the commission, Bernini’s studio produced at least two additional models of the fountain in wood and terra-cotta as part of the design process. After the fountain was completed, at least two additional models were commissioned of Bernini. One of these, in marble, has not been located. Another, in gilded bronze, is in the collection of the Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid. This model, skillfully cast in bronze, patinated, and with a textured finish, appears to date from the last part of the 17th century. Its base—rockwork, figures, and ornament—is original, while the obelisk and basin are modern replacements.

Micromosaic table top c. 1865

Cesare Roccheggiani (active mid- to late 19th century)

glass micromosaic, rosso antico, further malachite frame in Belgian black marble base

26 x 1.5 in

L2016.2101.034

No micromosaic studio was more prolific—and very few more accomplished—than that led by Cesare Roccheggiani, who opened a shop on Rome’s Via Condotti in 1874. By 1900, the shop expanded to include three addresses and offered a wide range of decorative arts. This tabletop includes eight highly realized views of Rome’s most famous ancient monuments arranged around a circular image of Saint Peter’s Square. This design, also including the stylized Greek Key border, rosso antico trim, and malachite frame, is characteristic of Roccheggiani’s work. The use of imported Belgian black marble for the ground was widespread in this period.

No micromosaic studio was more prolific—and very few more accomplished—than that led by Cesare Roccheggiani, who opened a shop on Rome’s Via Condotti in 1874. By 1900, the shop expanded to include three addresses and offered a wide range of decorative arts. This tabletop includes eight highly realized views of Rome’s most famous ancient monuments arranged around a circular image of Saint Peter’s Square. This design, also including the stylized Greek Key border, rosso antico trim, and malachite frame, is characteristic of Roccheggiani’s work. The use of imported Belgian black marble for the ground was widespread in this period.

This tabletop dates to the period between the late 1850s (when the gas lamps visible adjacent to the obelisk in the Square were installed) and 1883 (when the pair of bell towers visible atop the Pantheon were demolished). Tourists often purchased these tabletops without bases, which were built by cabinetmakers in their home countries. Most bases were low and Roman or Neoclassical in inspiration. This tabletop was discovered in the Philippines, on a base made of bamboo.

Porta Santa, Saint Peter’s Basilica 17th century

maker unknown

molded plaster on wood base

35 x 23.75 x 10.5 in

L2016.2101.020

This highly detailed model is finished on either side, representing both the exterior and interior facades of one of the world’s most famous doorways, the Porta Santa of Saint Peter’s Basilica. In a tradition dating to the 15th century, Holy Doors—immense doors located in Rome’s four patriarchal churches—are ceremoniously opened by the Pope during the Church’s Jubilee years, currently every quarter-century.

This highly detailed model is finished on either side, representing both the exterior and interior facades of one of the world’s most famous doorways, the Porta Santa of Saint Peter’s Basilica. In a tradition dating to the 15th century, Holy Doors—immense doors located in Rome’s four patriarchal churches—are ceremoniously opened by the Pope during the Church’s Jubilee years, currently every quarter-century.

In 1609, Pope Paul V appointed Carlo Maderno (1556–1629) as architect of Saint Peter’s. Michelangelo (1475–1564) had held this post from 1549 until his death, and set in motion much of the Basilica’s design. Maderno oversaw the completion of Michelangelo’s work, and, famously, modified the master’s plans. The palatial facade fronting Saint Peter’s Square, completed in 1612, is largely Maderno’s design. Other work still remained; in anticipation of the Jubilee year of 1625, Maderno turned his attention to the Basilica’s Porta Santa, which was fitted within the monumental doorway at the right-hand side along the portico.

Francesco Borromini (1599–1667) arrived in Rome in 1619 and was employed as a decorative sculptor on Maderno’s work at Saint Peter’s. By 1621, the future architect and enfant terrible of Rome’s Baroque era demonstrated sufficient talent to be placed in a position of some authority in the design and building of the Porta Santa. Borromini was likely responsible for the design of the doorway and certainly in charge of the carving of the brooding angel above its exterior. This type of distinctive, slightly ominous cherub recurs in many of the architect’s subsequent buildings.

Variations between the model and the executed work are subtle, primarily involving disparities in the type, proportions, arrangement, and sizes of decorative elements. Likely, this object was created as a presentation model for proposed changes to the Porta Santa. Most of the artifact is original, while the columns and molding at the top of the arch are modern replacements.

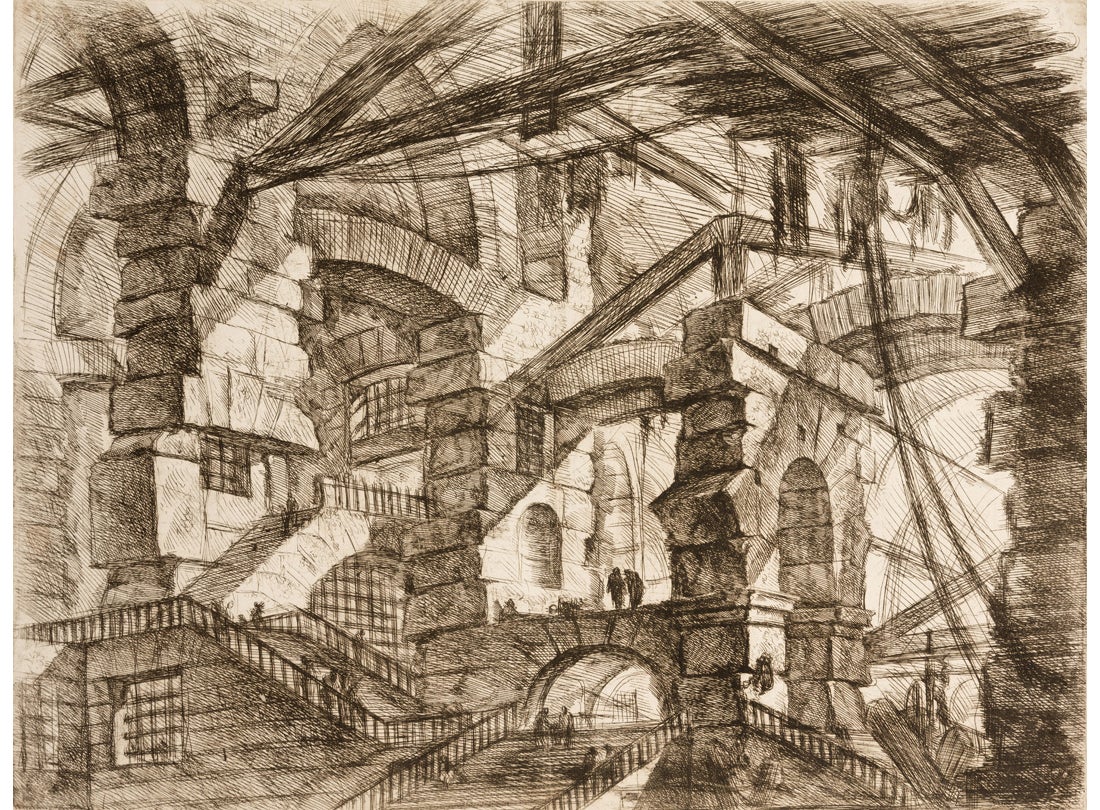

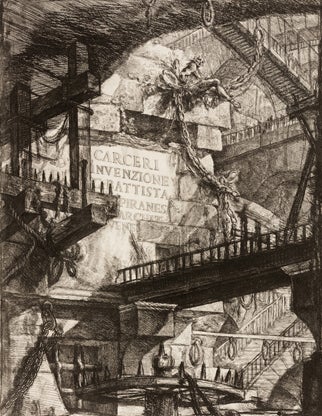

Plate XIV: The Gothic Arch 1749-50

Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons); 1st Edition; 14 Plates

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano Veneto 1720 – 1778 Rome)

etching on laid paper

15.75 x 21 in

L2016.2101.072

“I need to produce great ideas, and I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe, I would be mad enough to undertake it.”

—Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano Veneto 1720 – 1778 Rome)

Giovanni Battista Piranesi and the Carceri d’Invenzione

![Portrait of G.B. Piranesi in imitation of an antique bust 1750; Francesco Polanzani (Noale 1700 – 1783 Venice); Opere Varie di Architettura, prospettive, grotteschi; antichità; invetate, ed incise da Giambattista Piranesi Architetto Veneziano]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/12a_piranesi_roads_to_rome.jpg) Giovanni Battista Piranesi arrived in Rome in 1740 at the age of twenty as a draftsman in the entourage of the Venetian ambassador to Pope Benedict XIV. Trained as an architect and with experience designing theatrical backdrops, we know from his own account that he was motivated by a desire to “learn from those august relics which still remain of ancient Roman majesty and magnificence, the most perfect there is of Architecture.” At the time, recent archaeological excavations in Italy were fueling a feverish interest in Rome’s antiquity, and the city was the primary destination of those travelling on the Grand Tour. Like other visitors, Piranesi was thoroughly seduced by his environment and became a lifelong champion of Rome’s art and architecture.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi arrived in Rome in 1740 at the age of twenty as a draftsman in the entourage of the Venetian ambassador to Pope Benedict XIV. Trained as an architect and with experience designing theatrical backdrops, we know from his own account that he was motivated by a desire to “learn from those august relics which still remain of ancient Roman majesty and magnificence, the most perfect there is of Architecture.” At the time, recent archaeological excavations in Italy were fueling a feverish interest in Rome’s antiquity, and the city was the primary destination of those travelling on the Grand Tour. Like other visitors, Piranesi was thoroughly seduced by his environment and became a lifelong champion of Rome’s art and architecture.

Upon his arrival, Piranesi focused his attention on the printmaking business in the hopes of finding employment. After a brief and unhappy internship with Rome’s then-preeminent etcher, Giuseppe Vasi (1710 – 82), Piranesi began producing his own views of the city, or vedute, which were popular with tourists wishing to return home with a souvenir of Rome’s antiquity. Piranesi developed the veduta as an interpretive instrument in his archaeological study of Rome’s ruins, ultimately producing more than one thousand distinct etchings.

While today, Piranesi is remembered as a graphic artist, it should not be forgotten that he was, as well, an architect, furniture designer, dealer in classical antiquities, historian, and importantly, among the very first architectural preservationists. Without Piranesi, and the eloquent argument of his etchings testifying to the importance of the city’s ancient ruins, Rome would now be a very different, much diminished place.

In 1749–50, Piranesi produced a series of fourteen etchings that focused exclusively on the enclosed interiors of prisons. Unlike many of his later vedute produced with specific appeal to the Grand Tourist, these dark and foreboding scenes are the fullest expressions of Piranesi’s vivid and macabre imagination. The fantastic perspectives bear no resemblance to the cramped spaces of Rome’s prisons at that time. Perhaps owing to his training in theatrical design, these views appear more as grand and menacing stage sets. Vast and cavernous, with lofty arches rising to imperceptible heights, they simultaneously evoke limitless space and claustrophobic oppression. Piranesi returned to this series again and again, reworking the existing plates and adding two more to produce a second edition of sixteen darker and more detailed etchings in 1760, retitled Carceri d’Invenzione—imaginary prisons. They feature additional bridges, platforms, and a variety of elements—ropes, wheels, spikes, and hooks—that make the prison look like one hellish mechanism.

In 1749–50, Piranesi produced a series of fourteen etchings that focused exclusively on the enclosed interiors of prisons. Unlike many of his later vedute produced with specific appeal to the Grand Tourist, these dark and foreboding scenes are the fullest expressions of Piranesi’s vivid and macabre imagination. The fantastic perspectives bear no resemblance to the cramped spaces of Rome’s prisons at that time. Perhaps owing to his training in theatrical design, these views appear more as grand and menacing stage sets. Vast and cavernous, with lofty arches rising to imperceptible heights, they simultaneously evoke limitless space and claustrophobic oppression. Piranesi returned to this series again and again, reworking the existing plates and adding two more to produce a second edition of sixteen darker and more detailed etchings in 1760, retitled Carceri d’Invenzione—imaginary prisons. They feature additional bridges, platforms, and a variety of elements—ropes, wheels, spikes, and hooks—that make the prison look like one hellish mechanism.

![Plate IX: The Giant Wheel 1760; Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons); 2nd Edition; 16 Plates; Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano Veneto 1720 – 1778 Rome); etching on laid paper; 21.75 x 16 in; L2016.2101.073]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/12c_piranesi_roads_to_rome.jpg) Piranesi’s technique was highly original, relying on the rapid sketch rather than the finished drawing. His pictorial approach defied the conventional linear approach to the medium, earning the scorn of Vasi, who dismissed the newcomer as too much of a painter to ever become an etcher. But contemporaries admired the freshness of Piranesi’s compositions, praising his draftsmanship and his powers of improvisation on the plate itself. Piranesi’s hand-drawn effect resulted from first etching with a stylus on waxed copper plates, and then burnishing away sharper lines while the plate was set in an acid bath. This series displays the artist’s remarkable ability to convey light penetrating from above, with darkening shadows falling upon vaulted walls that recede in the distance.

Piranesi’s technique was highly original, relying on the rapid sketch rather than the finished drawing. His pictorial approach defied the conventional linear approach to the medium, earning the scorn of Vasi, who dismissed the newcomer as too much of a painter to ever become an etcher. But contemporaries admired the freshness of Piranesi’s compositions, praising his draftsmanship and his powers of improvisation on the plate itself. Piranesi’s hand-drawn effect resulted from first etching with a stylus on waxed copper plates, and then burnishing away sharper lines while the plate was set in an acid bath. This series displays the artist’s remarkable ability to convey light penetrating from above, with darkening shadows falling upon vaulted walls that recede in the distance.

![Plate VI: The Smoking Fire 1749-50; Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons); 1st Edition; 14 Plates; Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano Veneto 1720 – 1778 Rome); etching on laid paper; 21.25 x 15.75 in; L2016.2101.081]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/12d_piranesi_roads_to_rome.jpg) Piranesi’s carceri reflect his fascination with and understanding of the subterranean world in and around his adopted city—the buried cisterns of Castel Gandolfo, the underground vaults of Hadrian’s Villa, and the catacombs along the Appian Way. While he unites and grounds his interiors with a real architectural vocabulary, he purposely employs disorientating invention. Piranesi freely rearranges planes to suit his compositions—cables from pulleys draw improbable lines (Plate VI: The Smoking Fire); a circular opening is inexplicably placed over a grilled doorway to an open space (Plate IX: The Giant Wheel); and beams intersect interior walls with no clear structural function (Plate XIV: The Gothic Arch). As with Piranesi’s exterior views of Rome’s ruins, the scale of his imagined interiors is exaggerated by diminutive figures occupying stairwells and platforms, apparently free to move about, but clearly trapped within an overbearing architecture.

Piranesi’s carceri reflect his fascination with and understanding of the subterranean world in and around his adopted city—the buried cisterns of Castel Gandolfo, the underground vaults of Hadrian’s Villa, and the catacombs along the Appian Way. While he unites and grounds his interiors with a real architectural vocabulary, he purposely employs disorientating invention. Piranesi freely rearranges planes to suit his compositions—cables from pulleys draw improbable lines (Plate VI: The Smoking Fire); a circular opening is inexplicably placed over a grilled doorway to an open space (Plate IX: The Giant Wheel); and beams intersect interior walls with no clear structural function (Plate XIV: The Gothic Arch). As with Piranesi’s exterior views of Rome’s ruins, the scale of his imagined interiors is exaggerated by diminutive figures occupying stairwells and platforms, apparently free to move about, but clearly trapped within an overbearing architecture.

![Plate XV: The Pier with a Lamp 1749-50; Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons); 1st Edition; 14 Plates; Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano Veneto 1720 – 1778 Rome); etching on laid paper; 16 x 21.5 in; L2016.2101.069]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/12e__piranesi_roads_to_rome.jpg) These images resonated with successive generations of viewers and their impact is widespread and lasting. The unnerving terror and awe they convey inspired work by the Romanticists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, including, quite directly, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Pit and the Pendulum (1842). The dystopian vision of Piranesi’s vast interiors is evident in the underground city of filmmaker Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and echoes in the paintings of early 20th century Surrealists. And one can hardly imagine the trick perspectives rendered by M. C. Escher (1898–1972) without the precursor of Piranesi’s impossible arrangements of stairwells. Just as the artist’s vedute of Rome’s ancient architecture continue to inform our perspective of the Eternal City, so too do these prisons of his invention remain with us—an imagined universe that has become real in our collective subconscious.

These images resonated with successive generations of viewers and their impact is widespread and lasting. The unnerving terror and awe they convey inspired work by the Romanticists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, including, quite directly, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Pit and the Pendulum (1842). The dystopian vision of Piranesi’s vast interiors is evident in the underground city of filmmaker Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and echoes in the paintings of early 20th century Surrealists. And one can hardly imagine the trick perspectives rendered by M. C. Escher (1898–1972) without the precursor of Piranesi’s impossible arrangements of stairwells. Just as the artist’s vedute of Rome’s ancient architecture continue to inform our perspective of the Eternal City, so too do these prisons of his invention remain with us—an imagined universe that has become real in our collective subconscious.