International Terminal

![Mayflower [and] Galatea, the start 1886](/sites/default/files/07_america%27s_cup_sfom.jpg)

![Volunteer turning S.H. [i.e. Sandy Hook] Lightship, Sept. 27 1887](/sites/default/files/08_america%27s_cup_sfom.jpg)

![The start [Vigilant and Valkyrie II] 1893](/sites/default/files/09_america%27s_cup_sfom.jpg)

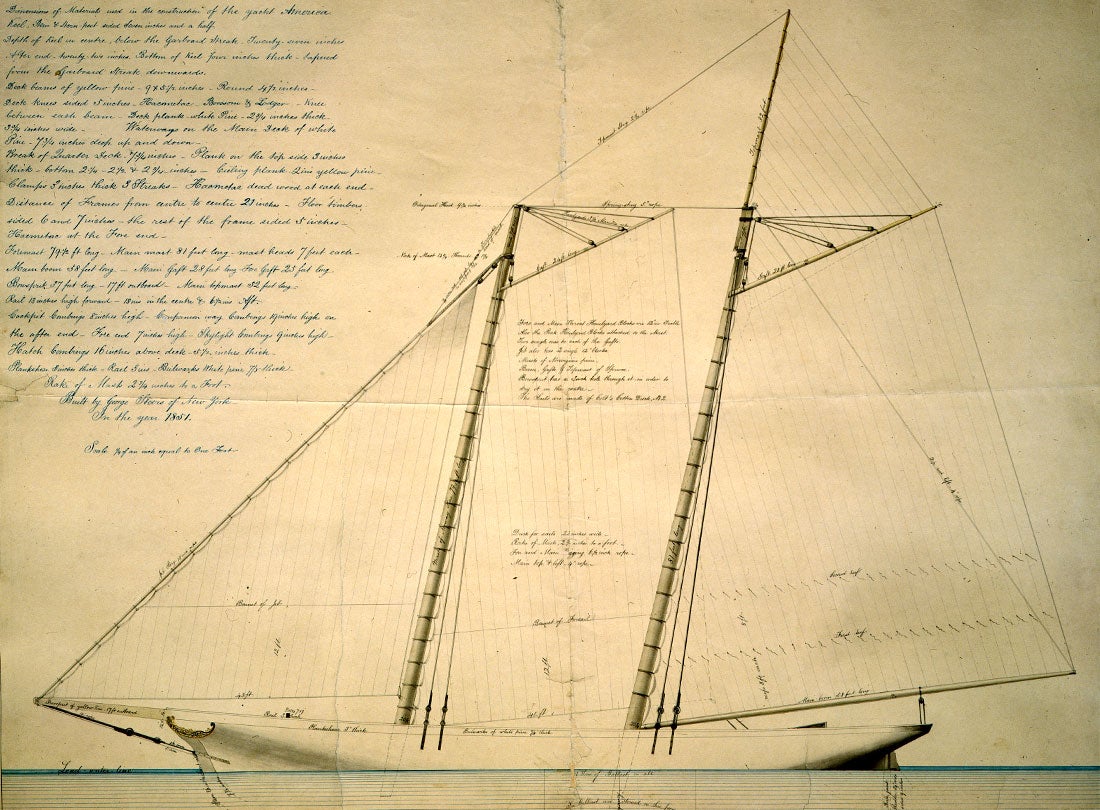

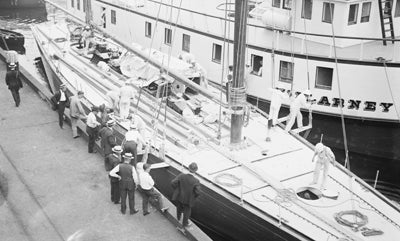

Rigging and sail plan for America October 31st, 1851

Scale ¼”=1’

Drawn by John F. Sherman

paper, ink, watercolor

Mystic Seaport

1979.22

L2013.1801.020

1851: America and the Race for the Hundred-Sovereign Cup

It is no coincidence that the origins of America’s Cup competition coincide with the first world’s fair, London’s Great Exhibition in 1851. A showcase for the greatest industrial achievements of the day, the event attracted the attention of Commodore John Cox Stevens of the recently established New York Yacht Club, who commissioned a yacht to sail to England and demonstrate America’s prowess at both shipbuilding and sailing.

The schooner, fittingly named America, was modeled on the highly successful pilot boats that navigated New York’s busy harbor. A stark contrast to the “cod’s head and mackerel tail” shape that typified British yachts, America had a long, sharp bow and a blunted stern. Her masts were sharply raked and rigged with taut cotton duck sailcloth, which stretched less than the flax sails used by the British, providing more power in varying wind conditions.

Upon crossing the Atlantic, America’s unusual appearance made an immediate impression, with one British sailor declaring, “If she’s all right, then we’re all wrong.” Stevens found no takers for his audacious challenge—a race against any yacht for the astronomical stakes of £10,000, nearly 1.5 million dollars in today’s value. After a scolding by the British press for demonstrating a lack of honor and courage, The Royal Yacht Squadron extended an invitation to America for a race against their fleet at the club’s annual fifty-three-nautical mile race around the Isle of Wight. The winner received no cash prize, but would take ownership of the club’s trophy, which had been commissioned just three years earlier.

The race began at 10:00 am with a standing start for all parties. After steadily working her way through a crowded field of sixteen yachts, America took the lead less than two hours into the race and never relinquished it. Halfway through the course, she led by two-and-a-half miles. Proving fast even in the periodically light winds, she extended her lead over all but one, finishing ahead of the far smaller cutter Aurora by approximately eight minutes.

While America was the beneficiary of some confusing course instructions, and several competitors dropped out due to mishaps, her victory was largely attributed to several factors extending beyond luck: the boat’s technical superiority; excellent sailing by Captain Dick Brown and his eighteen-man crew; and perhaps most importantly, efficient management by an ambitious syndicate, led by Stevens, whose sole focus was to demonstrate that America was the fastest yacht on the seas.

The Cup

The trophy won by America was neither extraordinary nor was it an actual cup. It was an ornately decorated bottomless ewer crafted from sterling silver. When commissioned by the Royal Yacht Squadron in 1848, it was simply referred to as the club’s “Hundred-Sovereign Cup,” indicating its cost. The victors at Cowes mistakenly called it the “Hundred-Guinea Cup,” while the American press referenced it as “The Queen’s Cup.” The trophy was ultimately renamed “America’s Cup” when donated by the syndicate to the New York Yacht Club in 1857, although an early and affectionate term for the trophy by participants and public alike endures—“The Auld Mug.”

The trophy won by America was neither extraordinary nor was it an actual cup. It was an ornately decorated bottomless ewer crafted from sterling silver. When commissioned by the Royal Yacht Squadron in 1848, it was simply referred to as the club’s “Hundred-Sovereign Cup,” indicating its cost. The victors at Cowes mistakenly called it the “Hundred-Guinea Cup,” while the American press referenced it as “The Queen’s Cup.” The trophy was ultimately renamed “America’s Cup” when donated by the syndicate to the New York Yacht Club in 1857, although an early and affectionate term for the trophy by participants and public alike endures—“The Auld Mug.”

The America, Winning the match at Cowes for the Club Cup after 1851

lithograph by Oswald W. Brierly

Mystic Seaport

1975.187.2

R2013.1801.050

Detail from Finish—First International Race for America’s Cup August 8, 1870

oil on canvas painting by Samuel Colman (1832–1920)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

62.202

R2013.1807.001

1870: Magic defeats Cambria

“a liberal hearty welcome and the strictest fair play”

Although members of America’s syndicate had considered melting down the trophy to make souvenirs for themselves and their families, they decided on a more meaningful legacy. On July 8, 1857, the Cup was presented to the New York Yacht Club with a Deed of Gift establishing the trophy as “perpetually a Challenge Cup for friendly competition between foreign countries.” Three primary guidelines were established: official matches would be held between yacht clubs with the winning club taking possession of the Cup; after agreeing to match conditions, competitors would sail the course of the defender’s annual regatta; and the challenging club would grant six-months’ notice and declare the size and rig of its yacht so the defending club could sail a similar vessel.

The New York Yacht Club offered “a liberal, hearty welcome and the strictest fair play” in letters to yacht clubs in Britain, Canada, Belgium, Holland, and Russia, but no challengers came forth. The American Civil War of the 1860s essentially closed New York Harbor to pleasure sailing and the war exacerbated tensions with England, the presumed source of the most serious challenge for America’s Cup.

After the war’s conclusion in 1865, yachting competition resumed between the two nations and a challenge was eventually proposed and accepted. Englishman James Ashbury, the son of a railway carriage magnate, commissioned a large schooner and proposed a best-of-three series for ownership of the trophy on behalf of the Royal Thames Yacht Club. The New York Yacht Club accepted Ashbury’s challenge on the condition that he race against not one defender, but the Club’s fleet, just as America had raced against the entire Royal Yacht Squadron in 1851.

On August 8, 1870, New York’s inner harbor was crowded with Ashbury’s Cambria, seventeen defending yachts, and a fleet of more than fifty steamships carrying tens of thousands of curious spectators; many of them heavily intoxicated and wagering on the contest’s outcome. One reporter wrote, “the shores of Staten Island were like swarming cities.”

Cambria’s twelve feet of draft and enormous sails were not advantageous in the harbor’s narrow and shallow waters and she finished a distant tenth, more than forty minutes behind Magic, a much smaller centerboarder, and fourteen minutes behind fourth-place America, once again rigged as a sailing yacht and competing as a proud symbol of the nation’s technological prowess. Despite some grumbling about the crowded conditions, Ashbury gracefully accepted his defeat and promised to return shortly with a new yacht and a new challenge for the America’s Cup.

Saluting cannon from yacht Magic, used to warn spectators in crowded New York inner harbor course c. 1870

wood, bronze

Mystic Seaport

1954.394

L2013.1801.008.01-.02

Columbia c. 1871

photographer unknown

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

80.79.452

R2013.1801.026

1871: Columbia and Sappho defeat Livonia 4-1

Ashbury’s Second Challenge

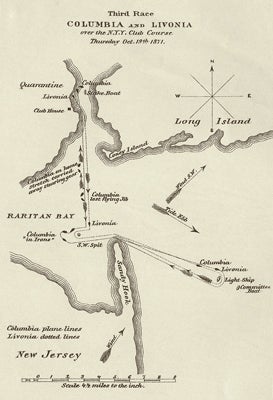

James Ashbury learned from his first challenge that the New York Yacht Club was prepared to interpret the Deed of Gift rules to its advantage in order to maintain possession of the Cup. After a protracted and acrimonious negotiation, the two parties agreed to sail one-on-one in a best-of-seven series, with the defender selected on each race day based on sailing conditions.

Ashbury argued for the race to be held in the open ocean off Newport, Rhode Island, where his British cutter with traditional deep hull was not disadvantaged against the American schooners with centerboards and shallower drafts. Unsurprisingly, the Club rejected this proposal, but agreed to sail three races on New York’s harbor course, three on the ocean off the coast of Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and if necessary, a final race on a course to be agreed upon.

Ashbury arrived with Livonia, twenty feet longer and carrying more than twice as much sail as her predecessor, Cambria. Of the New York Yacht Club’s four top schooners, Columbia was considered the Club’s best light-air boat and easily defeated the much larger challenger in low-wind conditions. Columbia won the second race amidst great controversy when Livonia was not properly instructed on how it should pass the mark in a course inexplicably shorter than had been announced. Although the committee rejected his protest, Ashbury considered the contest even.

Columbia lost the third race after becoming partially disabled in strong winds and limping across the finish line with a rigged emergency tiller. Sappho, the Club’s 135-foot schooner, was enlisted to continue the Club’s defense in strong winds and soundly thrashed Livonia in two consecutive races to retain the Cup by an official margin of four-to-one. Ashbury, however, considered the score three-to-two and declared his intent to continue racing. When no challengers appeared at the starting line on October 25, Ashbury claimed victory by default and demanded the Cup.

After returning to England empty-handed, Ashbury expressed outrage at the “unfair and unsportsmanlike proceedings” of the New York Yacht Club. The two parties continued a war of words in the press and returned trophies previously awarded to one another. Although neither Ashbury nor the Club was blameless in the dispute, many American newspaper editorials sympathized with the challenger. One journalist chided the New York Yacht Club for making “preparations so carefully as to leave Mr. Ashbury no chance whatsoever of winning.” In the Cup’s second defense, the idea of a “perpetual” contest with “friendly competition” between nations was already in jeopardy.

Course map from third race in second defense of America’s Cup 1874

The America Cup: A Nautical Poem by Hamilton Morton

G. P. Putnam and Sons, New York

paper, pigments, ink

Collection of Herreshoff Marine Museum/America’s Cup Hall of Fame

L2013.1802.013

“A stern chase and a long one – 1876. Countess of Dufferin, America, Grant, Madeleine” c. 1876

lithograph by Frederic S. Cozzens (1846–1928)

Mystic Seaport

1956.865

R2013.1801.051

1876: Madeleine defeats Countess of Dufferin 2-0

A Challenge “more courageous than wise”

The Ashbury affair strained relations between the British and American yachting communities and it was soon apparent that no new challenge would be issued. With both its membership and its finances sagging, the New York Yacht Club was happy to receive the challenge that eventually arrived in the spring of 1876, albeit from an unlikely source, Major Charles Gifford of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club of Toronto.

Gifford challenged with Countess of Dufferin, a yacht designed by Alexander Cuthbert that was essentially a larger, two-masted version of the fastest sloop on Lake Ontario. Unfortunately for Gifford, the translation was not successful. The yacht’s chances were further diminished by the hurried pace of her construction, poorly fit sails, and the lackadaisical manner in which her amateur crew approached the contest. Their only opportunity for much-needed training was during her passage down the St. Lawrence River to New York; a voyage described by onlookers as a relaxed cruise.

Despite Countess of Dufferin’s obvious shortcomings and a campaign that even a member of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club characterized as “more courageous than wise,” she was rumored to be fast and American journalists warned that American possession of the Cup was in peril. But when the challenger finally arrived for the race, she suffered by comparison to the defender and was derided as an unworthy challenger by many yachting critics.

The Club’s defender, Madeleine, who easily vanquished her competition in trials, was the antithesis of the Canadian challenger. She possessed a sleek and graceful form, was expertly handled by a professional crew, and proved remarkably fast on the water. Her sails were beautifully cut and her copper bottom burnished smooth with tallow.

Unsurprisingly, Countess of Dufferin was trounced in two consecutive races, and even lost to America, which was sailing alongside for sport twenty-five years after her victory at Cowes. Although it was easy for critics to ridicule an effort that seemed inadequate in many aspects, it is not inconceivable that the contest for the America’s Cup could have ended altogether if not for the Canadians stepping into the breach.

A Curious Entry

During the New York Yacht Club’s centennial regatta in the summer of 1876, a young yacht designer from Bristol, Rhode Island, appeared in a strange-looking vessel with two hulls and only twenty-five feet long. Nathanael G. Herreshoff’s Amaryllis easily defeated each of the larger yachts. But in an era that seemed to value an excess of both size and expense in all things, Herreshoff’s catamaran was simply too small and too inexpensive to be considered as an acceptable racing yacht, and the Club expressly prohibited any such vessel from competing for the Cup.

Patent model for Nat Herreshoff’s catamaran April 10, 1877

Nathanael Greene Herreshoff (1848–1938)

wood, wire

Collection of Herreshoff Marine Museum/America’s Cup Hall of Fame

L2013.1802.005

Mischief 1891

photograph by Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-5629

R2013.1805.004

1881: Mischief defeats Atalanta 2-0

Canada’s Second Challenge

Five years after Madeleine’s overwhelming victory over challenger Countess of Dufferin, the New York Yacht Club fielded another Canadian challenge, this time from a little-known yacht club one hundred miles east of Toronto. Alexander Cuthbert, designer of Canada’s previous challenger, entered Atalanta—a mere seventy feet long and the smallest challenger yet. Club members were pleased to answer the challenge with a similarly sized boat that would not result in a time allowance granted to the Canadians.

In the years between the two Canadian challenges, a series of fatal accidents had convinced many that the design of the shallow-draft “skimming dishes” sailed by Americans had become too extreme, proving unstable and dangerous in rough seas and heavy winds. New designs featured narrower hulls of greater depth, which were weighted with lead ballast and fitted with a centerboard to work through the hull’s keel. Thus began a trend toward a compromise between typically shallow-draft American schooners and the deep-keeled cutters favored by the British.

Financial setbacks delayed the completion of Atalanta, whose hasty construction resulted in a rough-surfaced hull. Her arrival was further delayed when she proved too wide for delivery down the Erie Canal and required towing on her side by a team of mules—an undignified journey that was ridiculed by American journalists.

Perhaps to escape accusations of interpreting the rules of deed to gain an unfair advantage, the New York Yacht Club declared that a single defender would race throughout the series. Three of the Club’s flag officers formed a syndicate to commission a yacht to specifically meet Cuthbert’s challenge, but their entry Pocahontas was surprised in her trials by Mischief; only the second iron yacht built in the United States and the first to be designed with scientific drawings rather than simply scaling up from a carved model.

Spinnakers, the ballooning sails favored by the British and previously banned at New York Yacht Club races, were allowed for the first time. Unfortunately for Atalanta, she was over-rigged for the windy conditions and mishandled by her mostly amateur crew in two blowout losses to Mischief. The press was merciless in their ridicule of the overmatched Canadians, with one reporter describing Atalanta “with sails that fitted like a Chatham Street suit of clothes, and bungled around the course by an alleged crew, who would have been overmatched in trying to handle a canal boat anchored in a fog.” Cuthbert, undeterred, announced his intention to challenge once again in the spring of 1882.

Hull line drawing from ship's plans for yacht Mischief 1881

Smith, A. Cary; Harlan & Hollingsworth Corp.

Mystic Seaport

SP.38.269

R2013.1801.053

Puritan at sea c. 1885

photographer unknown

Mystic Seaport

R2013.1801.028

1885: Puritan defeats Genesta 2-0

A New Deed and a “compromise sloop”

Despite Alexander Cuthbert’s intentions to launch a third Canadian campaign, the New York Yacht Club was reluctant to race against a twice-defeated challenger. The Club had the larger concern of the America’s Cup competition becoming diminished as a regional contest. A new Deed of Gift eliminated Cuthbert’s hopes for another challenge: participating clubs must conduct their races on salt water; the loser may not challenge again within two years; and challengers must sail to the event on their own hulls. Significantly, the new deed also formalized the decision that a single yacht would be designated to defend the Cup for the entire race series.

British yacht designer John Beavor-Webb, perhaps enticed by these new rules, presented a paired challenge from two of his clients for August and September of 1885. The New York Yacht Club agreed, but on the condition that the challenges be separated by a year’s time; Sir Richard Sutton’s Genesta was scheduled to challenge that fall and Lieutenant William Henn’s Galatea would return the following year for a challenge

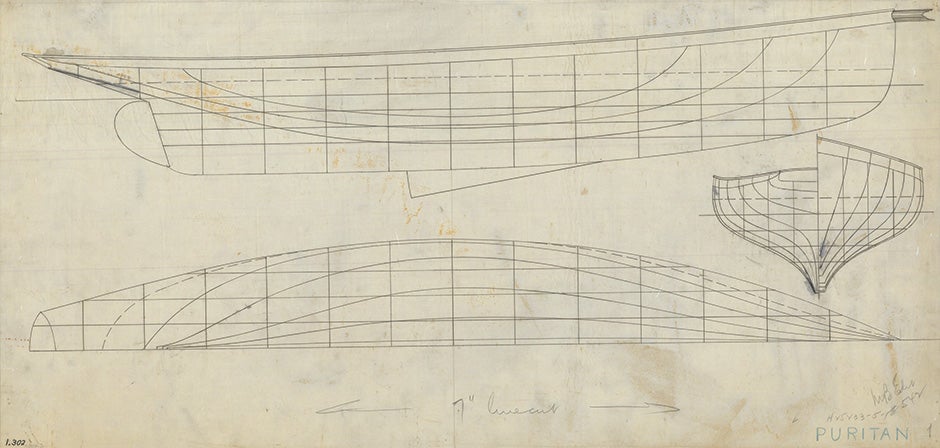

Hull line drawing from ships plans for yacht Puritan 1885

drawn by W. P. Stephens Mystic Seaport

SP.1.302

R2013.1801.054

Puritan was funded by Eastern member John Malcolm Forbes, managed by New York Yacht Club member Charles Paine, and most significantly, designed by Eastern’s young secretary, Edward Burgess. A sailor since his youth, Burgess was a professor of Entomology at Harvard prior to becoming a naval architect. A summer spent on the Isle of Wight resulted in an appreciation for the strengths of English cutters, which he applied scientifically to his ninety-four-foot “compromise sloop” that borrowed from both American and English traditions.

Burgess silenced detractors on either side of the Atlantic when Puritan won both races against her highly regarded challenger, but not before a remarkable display of sportsmanship on the part of Sutton. After being advised by the race committee to continue sailing after a foul by Puritan resulted in her being disabled, Sutton refused, explaining, “We want a race…we don’t want a walkover.” Such sportsmanship was rare in Gilded Age New York and Sutton was publicly praised for his honorable behavior and “graceful magnanimity.” It appeared as if the contest was again living up to its original proposal as a “friendly competition” between foreign nations.

Puritan crew on deck 1885

photographer unknown

Mystic Seaport

R2013.1801.029

Burgess silenced detractors on either side of the Atlantic when Puritan won both races against her highly regarded challenger, but not before a remarkable display of sportsmanship on the part of Sutton. After being advised by the race committee to continue sailing after a foul by Puritan resulted in her being disabled, Sutton refused, explaining, “We want a race…we don’t want a walkover.” Such sportsmanship was rare in Gilded Age New York and Sutton was publicly praised for his honorable behavior and “graceful magnanimity.” It appeared as if the contest was again living up to its original proposal as a “friendly competition” between foreign nations.

Mayflower [and] Galatea, the start 1886

photograph by John S. Johnson, Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-62418

R2013.1805.006

1886: Mayflower defeats Galatea 2-0

A Well-Appointed Challenger

The New York Yacht Club formally accepted William Henn’s challenge shortly after the 1885 match and commissioned Edward Burgess to design a new defender to compete against Galatea, which was six feet longer than the previous challenger. Mayflower was similar in design to her predecessor Puritan but with a longer and finer bow. Unlike Puritan, she failed miserably in her trials with a centerboard that would not lower properly and an incorrect sail trim, causing great concern in the public and the press. After corrections, however, she performed well and was selected to defend the Cup.

Galatea’s arrival in New York caused a sensation. Described as a “cruising man by temperament,” Henn and his wife made a leisurely Atlantic crossing in accommodations considered extravagant by any standards, but particularly for a yacht intended for racing. The salon below deck was furnished with fine furniture, linens, artwork, animal skin rugs, and a collection of potted plants that increased in number after the public learned of Mrs. Henn’s interest in horticulture. The couple also brought with them a menagerie of pets, including several dogs, a cat, a raccoon, and a monkey named Peggy who, according to press accounts, assisted the crew in a variety of tasks.

Henn’s easygoing manner and casual approach to training led to speculation that he was disguising the true speed of his challenger. The personal popularity of the Henns and rampant speculation about his yacht’s capabilities resulted in an unprecedented number of spectator boats crowding the harbor on race day. When the challenge began, however, Galatea proved no match for Mayflower and lost in consecutive races held in relatively poor winds and heavy fog. The only controversy arose when the New York Yacht Club rejected Henn’s request for a shorter course after becoming ill prior to the second race. Although Henn gracefully accepted the decision, the British press took exception to the exchange.

Despite his disappointment with the weather and the results, Henn countered criticism from abroad that the American yachtsmen were unsportsmanlike and the American press and public too hostile. He declared his treatment completely fair and cited his wife’s great pleasure with the visit. But Henn declined when asked if he would compete again, stating that the Royal Yacht Squadron “hardly thinks the game is worth the hunting.” Henn kept Galatea in New York Harbor and raced her in American waters during the 1887 season. Just prior to the Henns returning to England, Peggy the monkey died. She was wrapped in a Union Jack, carried by four skippers from nearby yachts, and given a proper burial at sea. The fate of the rest of the Henns’ menagerie is unknown.

Galatea, below deck c. 1886

photographer unknown

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

R2013.1801.030

Henn’s easygoing manner and casual approach to training led to speculation that he was disguising the true speed of his challenger. The personal popularity of the Henns and rampant speculation about his yacht’s capabilities resulted in an unprecedented number of spectator boats crowding the harbor on race day. When the challenge began, however, Galatea proved no match for Mayflower and lost in consecutive races held in relatively poor winds and heavy fog. The only controversy arose when the New York Yacht Club rejected Henn’s request for a shorter course after becoming ill prior to the second race. Although Henn gracefully accepted the decision, the British press took exception to the exchange.

Despite his disappointment with the weather and the results, Henn countered criticism from abroad that the American yachtsmen were unsportsmanlike and the American press and public too hostile. He declared his treatment completely fair and cited his wife’s great pleasure with the visit. But Henn declined when asked if he would compete again, stating that the Royal Yacht Squadron “hardly thinks the game is worth the hunting.” Henn kept Galatea in New York Harbor and raced her in American waters during the 1887 season. Just prior to the Henns returning to England, Peggy the monkey died. She was wrapped in a Union Jack, carried by four skippers from nearby yachts, and given a proper burial at sea. The fate of the rest of the Henns’ menagerie is unknown.

Volunteer turning S.H. [i.e. Sandy Hook] Lightship Sept. 27 1887

photograph by John S. Johnston, Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-21987

R2013.1805.008

1887: Volunteer defeats Thistle 2-0

Running Away from the Competition

Shortly after their successful defense against Lieutenant Henn’s Galatea, the New York Yacht Club received a new challenge from Scotland’s Royal Clyde Yacht Club. The challenger’s designer George Lennox Watson intended to keep the Americans guessing throughout the buildup to the Cup races. His creation was shrouded in secrecy and hidden in its shed during construction. Watson only revealed that her waterline length would be about that of Mayflower, the previous defender.

After extensive research on New York Harbor’s sailing conditions, Watson rigged his challenger, Thistle, with an extraordinary 9,000 square feet of sail to deal with the light winds he predicted. Watson’s prognosis also led him to reduce the lateral profile of Thistle’s keel to lessen her resistance in the water. Meanwhile, Edward Burgess was busy designing a defender for a third consecutive year. Larger and faster than his previous creations, Volunteer dominated the summer’s racing season and easily handled Mayflower in trials to win the right to defend the Cup.

When Thistle and Volunteer were finally viewed side-by-side, their similarities astonished observers. Thistle was wider than her predecessor Galatea, and only three feet narrower than her competitor. Both possessed the graceful bows of a clipper, and both possessed hulls that had been pared down from those of previous models. The primary difference remained the enduring traditions of both nations’ yachtsmen—centerboards and steering wheels for the Americans; deep keels and tillers for the British.

Unfortunately, scandal erupted when Thistle’s waterline was measured at nearly eighty-seven feet, longer than the promised eighty-five feet. Although the difference would certainly be compensated by time allowances, New York Yacht Club members expressed outrage and threatened to cancel the match, but relented when they discovered no evidence of bad faith on Watson’s part.

Despite the buildup, the races ended up disappointing those hoping for a spirited contest. Volunteer proved to be a magnificent performer. She was brilliantly managed by her owner General Charles Jackson Paine; expertly handled by Captain Hank Haff; and easily defeated Thistle in both races. Burgess and Paine returned to Boston where they were celebrated with a grand banquet at Faneuil Hall. Unable to attend, Oliver Wendell Holmes cabled his regrets, noting that Paine was the only general “I ever heard of whom made himself illustrious by running away from all his competitors.”

For his part, Watson nobly accepted responsibility for defeat. He believed he was excessive in whittling away Thistle’s undersides, leaving her vulnerable to sliding sideways under her colossal sails. Despite his public contrition, Thistle was considered one of the greatest challengers in the competition’s early history, and Watson’s ideas were successfully imitated and carried still further in the designs of the next generation of Cup contenders.

Half-hull models for defender Volunteer and challenger Thistle n. d. Sonny Hodgdon (b. 1922)

wood, paint, brass

Collection of Herreshoff Marine Museum/America’s Cup Hall of Fame

L2013.1802.031, .032

The start [Vigilant and Valkyrie II] 1893

photograph by Henry G. Peabody, Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-5420

R2013.1805.010

1893: Vigilant defeats Valkyrie II 3-0

“a vicious kind of yacht”

Harboring ill feelings from the dispute over Thistle’s dimensions, and wishing to rebuff a challenge that arrived on the same day that Volunteer had vanquished her foe, the New York Yacht Club created a third Deed of Gift to govern the Cup races. In addition to waterline length, challengers would now be required to provide the waterline beam, extreme beam, and the draft of their boats so American designers could better prepare for their opponent.

The Earl of Dunraven, an Irish lord, challenged on behalf of the Royal Yacht Squadron but withdrew when told by the New York Yacht Club that he could not rescind the new deed’s rules if he won. The Club’s claim that their written document provided absolute ownership of a trophy that had been purchased and awarded by the Royal Yacht Squadron further exacerbated longstanding tensions between New York’s wealthiest businessmen and the English aristocrats. After several failed attempts to negotiate the rules of deed, Dunraven relented and the Club accepted his challenge with Valkyrie II, a new yacht designed by George Watson.

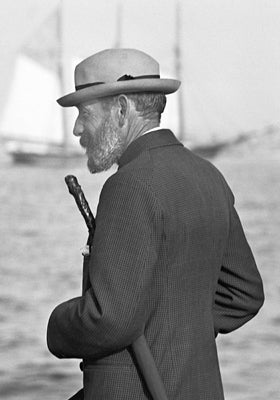

The defender was designed and built by the same man who frightened the New York Yacht Club rules committee nearly two decades earlier with his catamaran Amaryllis. Nathanael Herreshoff, along with his brother John, had revolutionized the boating world with a series of innovative steam yachts from their boatyard in Bristol, Rhode Island. Now, “Captain Nat” was creating radical new sailboats that looked nothing like what had gone before. Herreshoff’s Vigilant was a massive centerboard sloop with all-metal construction and unique fittings custom-crafted at the Herreshoff boat yard. At $100,000, she cost more than twice as much as Volunteer and required a crew of seventy compared to Volunteer’s thirty. Vigilant was described by one critic as a prototype for “a vicious kind of yacht, whose existence was more a curse than a blessing” due to her enormous size, her great cost, and the perceived danger of operating the 124-foot-long vessel with such shallow draft.

Indeed Herreshoff was the only man capable of helming Vigilant, which defeated a very fast Valkyrie II in consecutive races prior to giving the estimated crowd of 50,000 spectators the race of their lives. In the final contest, Vigilant chased down her competitor who suffered shredded spinnakers down the stretch, winning by just over two minutes—only forty seconds on corrected time. The New York Times called the contest “probably the greatest battle of sails that was ever fought.” The most exciting Cup race to date had left Lord Dunraven sputtering with excuses and accusations of foul play, but hopeful for success in another challenge.

Nathanael Greene Herreshoff, “The Wizard of Bristol” 1894

photograph by James Burton

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

B.1984.187.443

R2013.1801.031

Defender July 22, 1895

photograph by John S. Johnston, Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-33765

R2013.1805.012

1895: Defender defeats Valkyrie III 2-1

Controversy Returns to the Cup

When Lord Dunraven returned to challenge once again for the Cup, the New York Yacht Club decided to commission just one new defender, and Herreshoff’s new creation was called just that, Defender. To reduce her overall weight, Herreshoff employed aluminum on many parts that had been tobin bronze. And for the first time, the American representative was designed with a fin keel and no centerboard, a development that struck many of the country’s yachtsmen as heresy.

The trial races to confirm the defender were highly contentious. Previous defender Vigilant, newly refurbished with $50,000 by her owner and skippered by a brilliant young Scotsman named Charlie Barr, gave Herreshoff’s new boat several close races before Defender ultimately prevailed to win the Astor Cup and the right to defend against Valkyrie III.

Defender won her first America’s Cup race handily, but not without controversy. Dunraven protested that Defender was sailing at a lower waterline—thus longer in the water—than her pre-race measurement. After a delay to re-measure Defender, the committee rejected Dunraven’s claim and racing resumed amidst an enormous fleet with an estimated 60,000 spectators aboard more than 200 steamships and other vessels. A blundering spectator boat separated the two competitors at the starting line and when they converged, Valkyrie III’s long boom raked Defender’s deck and damaged her topmast shroud. Defender limped after her opponent and managed to finish just forty-seven seconds behind on corrected time.

After the committee ruled that Valkyrie III had fouled, the Americans offered to sail the race over, but Dunraven refused, claiming it was Defender who was at fault. He then declared his refusal to sail unless the course was cleared of the meddlesome spectators. Despite the committee’s efforts with a fleet of patrol boats, the problem persisted and Dunraven withdrew, leaving the Americans with a rather hollow victory and setting back Anglo-American yachting relations to the contentious days of James Ashbury’s challenges twenty-five years earlier.

Foxy old Hank and the Deer Isle boys

Defender was handled beautifully in her trials and in the Cup races by the “Deer Isle boys,” supremely talented sailors recruited from the small fishing community in Downeast Maine. This all-American crew, a first for defending crews that were previously composed mainly of Scandinavians, convincingly answered critics at home and abroad who felt America’s native-born sailors were not up to the task of defending the Cup. They were led by fifty-eight-year-old Henry Haff, who had served in the afterguard of earlier Cup winners Mischief and Mayflower and had previously captained Volunteer to victory against Thistle. In vanquishing this latest challenge, “foxy old Hank,” as he was called, became the oldest skipper to win the Cup and cemented his reputation as one of the greatest sailors of his generation.

Skipper Hank Haff at the wheel of Defender 1895

photographer unknown

Mystic Seaport

1951.12.13

R2013.1801.011

Columbia and Shamrock c. 1899

photograph by John S. Johnston, Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-62234

R2013.1805.013

1899: Columbia defeats Shamrock 3-0

Lipton’s challenge, and a mend in relations

With acrimony persisting from the 1895 challenge and an ongoing war-of-words in the press with the British yachting community, the New York Yacht Club was unsure when they could expect a new challenge. Beginning in April of 1897, rumors persisted of a challenge from the Marquis of Dufferin on behalf of Ireland’s Royal Ulster Yacht Club. Finally, on August 2, 1898, the Royal Ulster Yacht Club dramatically announced that the challenger was not Dufferin, but a much less aristocratic member, Sir Thomas Lipton.

Lipton, born to Irish parents in Scotland and reared in poverty, had briefly immigrated to the United States in his adolescence before returning to Scotland and becoming a grocery store magnate. Lipton’s tremendous wealth and fame were attributed to his mastery of what many consider to be the first merchandising campaign—luring previously unreached customers to purchase goods made affordable through his ownership of production chains, such as tea plantations in Ceylon and stockyards in the American Midwest. Although initiated as an “Irish challenge,” Shamrock was designed by Scotsman William Fife and she was built near London.

Meanwhile, a new defender was commissioned by a New York Yacht Club syndicate led by Commodore J. P. Morgan, who through his banking acquisitions had few peers in terms of wealth and power. Neither party showed any restraint in their pursuit of a winner, with Morgan’s syndicate spending an estimated quarter of a million dollars on Herreshoff’s Columbia, and Lipton spending perhaps twice that amount on Fife’s Shamrock.

More than a dozen U.S. Navy warships patrolled the harbor to prevent a repeat of the crowded conditions caused by spectator boats. Charlie Barr, who had lost in the previous Cup’s trial races, captained Columbia and handled her masterfully. Columbia won the first race by a large margin in less than ten knots of wind. Shamrock retired in the second race due to a broken topmast. The final race proved exciting, with Columbia leading by just seventeen seconds at the mark before beating back into twenty knots of wind and finishing more than six minutes ahead.

Although defeated, Lipton departed for England satisfied that publicity from his effort paid dividends, and he promised to challenge again in the first year of the new century. Through his great personal charm and sportsmanship, he had become the toast of New York and was given much of the credit for mending the tattered relations between the British and American yachting communities.

Sir Thomas Lipton aboard his yacht Erin 1899

photograph by James Burton

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

B.1984.187.445

R2013.1801.033

Shamrock II and Columbia maneuvering for the start Oct. 1, 1901

photograph by Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-21635

R2013.1805.015

1901: Columbia defeats Shamrock II 3-0

“close enough to speak to one another”

As promised, Lipton returned to challenge for the Cup in 1901, coaxing his old friend George Watson out of retirement to design his latest attempt at a “Cup-lifter.” Shamrock II was the first Cup yacht designed with the aid of a test tank, in which models were towed to help determine the most efficient form.

In trials to select a defender, Herreshoff’s Columbia, which had successfully defended the Cup two years earlier, competed against two very different opponents—Independence, an unorthodox scow-shaped yacht from Boston, and Herreshoff’s most recent creation, Constitution. Although Independence showed flashes of speed, her design proved too radical and poor construction doomed her performance.

Columbia, once again helmed by Charlie Barr, was hard-pressed by Constitution, arguably the fastest boat in the water and ably handled by her skipper, Uriah Rhodes. Barr, however, proved the difference maker. He handled Columbia “as a man would a bicycle,” taking chances that were considered highly dangerous and, although technically legal, reflected the rough-and-tumble tactics learned earlier during hard-fought contests against Captain Hank Haff. Columbia won all three races, but not without protest. On September 5, 1901, Barr earned the rare distinction of being disqualified from a race while being selected to defend the Cup.

The New York Yacht Club was wise to select the most aggressive captain, as the contest between Columbia and Shamrock II proved to be the closest to date. All three of the starts were hard fought and the challenger was first to the mark each time. Beating to windward, Barr sometimes had Columbia tacking twice as often as his opponent in an effort to gain every possible yard out of a windward shift or to secure a covering position on Shamrock II’s bow.

Prior to the start of the final race, both boats dueled for several minutes as neither wanted to go first and yield the more aggressive position. Finally, Columbia took off ahead in the nine-knot wind, but Shamrock gradually passed her and led by one minute at the mark. They then traded tacks for nearly an hour, with the crews described as “close enough to speak to one another.” Columbia, with forty-three seconds of allowance on handicap, never allowed Shamrock II to gain much separation and finished a mere two seconds behind, thus winning by forty-one seconds on corrected time in one of the most exciting finishes in Cup history. Despite Lipton’s second consecutive loss, he remained upbeat. Shamrock II had proved to be a fast boat indeed and the great sportsman, more popular than ever in the Cup’s host city, promised to return again with another challenger.

Life ring from America’s Cup defender Columbia 1899–1903

textile, cork, oil paint

Mystic Seaport

1947.965

L2013.1801.014

Reliance crossing the finish line August 25, 1903

photograph by Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-21776

R2013.1805.020

1903: Reliance defeats Shamrock III 3-0

Captain Nat’s magnificent “racing freak”

For his third challenge, Lipton returned to designer William Fife, who was assisted by the aging George Watson. After extensive tank testing, Shamrock III emerged as one of the most graceful Cup contenders yet produced—a beautifully proportioned form with a hull drawn down to the fin in the manner of full-bodied British racing cutters of previous generations. Remarkably, she was the first British challenger to use a wheel rather than the tiller that had been so sacred to British yachtsmen.

Meanwhile, Herreshoff was again called upon to design a defender capable of beating back Lipton’s challenge. Herreshoff kept the best elements from his previous creations while incorporating the radical, scow-like sections of Independence, which, despite her poor showing during the 1901 trials, had displayed flashes of remarkable speed. The result was Reliance, which at 144 feet long, 199 feet long at the top of her mast, and carrying more than 16,000 square feet of sail, was the biggest Cup defender ever built.

Herreshoff’s creation, even within the context of the increasingly extreme designs employed in Cup contenders, stood out among her peers with a dramatic fifty-four-foot overhang. She was condemned by critics on both sides of the Atlantic as “a racing freak,” unseaworthy, and too risky to be sailed in competition. She was crewed by sixty-four sailors. To control the massive craft, Herreshoff provided two steering wheels and an ingeniously designed hollow rudder that could be filled with water or pumped dry at the command of the helmsman. Reliance’s tremendous sail power was controlled by a unique system of sophisticated winches with ball bearings, automatic gears, and a host of other features never before seen in a yacht of any kind.

Predictably, Reliance overwhelmed her competitor in consecutive races. After a series of delays due to calms, fogs, and storms, Reliance completed her victory when she opened up such a lead that Shamrock III was forced to retire from the match. Lipton, dismissing praise for the beauty of his losing boat, declared, “I don’t want a beautiful boat. What I want is a boat to lift the Cup—a Reliance. Give me the homeliest boat that was ever designed, if she is as fast as Reliance.”

America’s Cup fatalities

America’s Cup racing experienced its first fatalities leading up to the 1903 match. At Weymouth, England, one sailor was knocked overboard and drowned after Shamrock III’s mast broke. Meanwhile, sailing in high winds and rough seas in her trials against Constitution and Reliance, three of Columbia’s crew went out on her bowsprit to set a jib topsail. After the yacht dipped into the heavy waves, her bow came up without one of the three sailors. After searching for more than an hour, the effort was abandoned.

Ship’s wheel from America’s Cup defender Reliance 1903

wood, brass

Mystic Seaport

1954.618

L2013.1801.015

Resolute and Shamrock IV, cutters at start of 5th race of the America’s Cup 1920

photograph by Morris Rosenfeld and Sons

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

1984.187.11282

R2013.1801.039

1920: Resolute defeats Shamrock IV 3-2

Sir Thomas’ “ugly duckling” and a Six-Year Layover

The great success of Herreshoff’s Reliance in the 1903 match caused a backlash against the increasingly large and dangerous racing yachts whose size was only governed by a designated waterline length of ninety feet. Herreshoff was aware that his engineering prowess had resulted in delicately built yachts capable of extraordinary speeds on the New York Yacht Club’s course, but not truly seaworthy. Indeed, Cup contenders were of little use beyond their competitions and were frequently scrapped shortly afterward.

After agreeing that the contenders would share waterline lengths of roughly seventy-five feet, The New York Yacht Club accepted Lipton’s fourth challenge for September 1914. Lipton’s earlier suggestion that he could care less about his boat’s appearance was confirmed when Shamrock IV was revealed to have a short bow, a squared off-stern, and was described by her own designer as “an ugly duckling.” Unsurprisingly, Herreshoff was working at an advantage while designing Resolute to conform to the standards for hull dimensions and sail allowance that he himself established, and the defender was awarded nearly seven minutes on handicap.

Shamrock IV was making her transatlantic voyage when she intercepted a German radio transmission announcing the start of what later became known as the World War I. Pausing at Bermuda, Shamrock IV traveled on to New York, where she remained a docked attraction for New Yorkers until the contest was finally resumed in 1920.

In the first race, Resolute built a lead of more than five minutes when her halyard broke and she became disabled. Shamrock IV completed the course and was awarded victory. Lipton, ever the sportsman, did not wish to win in that manner and offered to sail the race again, but the Club, perhaps aware of how this would be publicly received, refused. Although Lipton may have been dissatisfied by his victory over a crippled opponent, Shamrock IV’s victory in the second race gave him hope that he would finally take “the Auld Mug” back to its home.

Now needing only one win to secure the Cup, Shamrock IV gave Resolute a hard-fought race but was never able to shake the defender. For the first time in the event’s history, the competitors finished the course in exactly the same amount of time, with Resolute awarded victory due to the allowance granted. Seizing the momentum, the defender then took the series in convincing fashion, winning the last two races by considerable margins. Lipton, ever gracious in defeat, nonetheless was heartbroken at having come so close, and it was unclear if he would return to challenge again.

New Yorkers gather to gawk at Shamrock IV August 17, 1914

photograph by Bain News Service

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-B2-3194-4

R2013.1805.021

Interior of Enterprise, shown as efficiently equipped workshop with winches

and hand-me-downs inherited from Resolute, Vanitie, and Reliance 1930

photograph by Morris Rosenfeld and Sons

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

R2013.1801.043

1930: Enterprise defeats Shamrock V 4-0

“I canna win, I canna win”

Thomas Lipton, now eighty years old and much frailer, commissioned one more Shamrock for a final campaign in 1930. Contenders would now conform to the J-Class in the newly established Universal rules governing yacht design. Herreshoff developed and proposed the system, assigning alphabetical letters to indicate class specifications of size and displacement. J-Class boats were allowed waterline lengths of seventy-five to eighty-seven feet. Once again, the challenger was at a distinct disadvantage as the complicated formula was new to England, while the Americans had been operating with the system for several years.

In a stunning surge of boatbuilding, Americans produced four candidates of different lengths to determine the best possible defender. Enterprise, the smallest among her competitors, was a marvel of technological innovations and emerged as the strongest candidate. Designed by William Starling Burgess, son of the renowned designer of three consecutive Cup winners in the 1880s, Enterprise featured a lightweight duralumin mast and an ingeniously designed boom made with tracks and slides to optimize the shape of the mainsail.

Enterprise was financed, managed, and captained by Harold Vanderbilt, scion of one of America’s wealthiest families, whose father and uncle had financed earlier Cup defenders. A meticulous taskmaster, Vanderbilt left no detail unexamined in his approach to the contest. He assigned each crewmember to a station, with each identified by a number stitched onto their sweaters. Orders were given by number, not by name. Above and below deck, Enterprise was completely devoid of anything unrelated to function of the yacht. Eight of the twenty-six-man crew spent their entire time below, working the intricate system of winches in a yacht referred to as “that robust robot” and the “great box of clockwork.”

Shamrock V proved to be a fast yacht in trials and British hopes were high. Oddly, many American’s shared those sentiments. In what originated nearly eight decades earlier as the most nationalistic of contests, much of the country was rooting for the aging Lipton to finally realize his dream of “lifting the Cup” and returning it to its country of origin.

Unfortunately for Lipton and his many supporters, his fifth quest ended with familiar results. Enterprise won her four consecutive races with relative ease and as Lipton’s hopes were dashed, he was heard muttering dejectedly “I canna win, I canna win.” Ever gracious, Lipton became even more popular in his final defeat. Sympathy for Lipton even extended to Vanderbilt, who noted that his victory was “so tempered with sadness that it is almost hollow.” Before he left America for the last time, Lipton was feted at a grand banquet and awarded a magnificent trophy paid for by a public collection. Lipton died less than a year after returning home.

Interior of Enterprise, shown as efficiently equipped workshop with winches and hand-me-downs

inherited from Resolute, Vanitie, and Reliance 1930

photograph by Morris Rosenfeld and Sons

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

R2013.1801.043

Makeshift liquid compass from Shamrock V 1930

wood, metal, rope, sailcloth

Mystic Seaport

1975.210

L2013.1801.016

“This compass was used in 1930 aboard Sr. Thomas Lipton’s Shamrock V on her voyage home after losing the America’s Cup race to Enterprise. We encountered the center of a hurricane which washed the complete binnacle and regular compass overboard.”—Irving Johnson, First Mate, Shamrock V

Endeavour and Rainbow 1934

photograph from the Edwin Levick Collection

Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Virginia

122160

R2013.1806.006

1934: Rainbow defeats Endeavour 4-2

A New Challenger

With the death of Thomas Lipton, the task of challenging for the Cup fell to one of the few who could afford spending several hundred thousand dollars on a yacht in the midst of the Great Depression. Sir Thomas Sopwith, who had made his fortune as a pioneer in the airline industry, was also an accomplished skipper and was credited with engineering a number of racing yacht innovations. In 1934, he challenged with Endeavour on behalf of the Royal Yacht Squadron.

Harold Vanderbilt’s Rainbow, named to inspire optimism during terrible economic times, was made on the cheap relative to earlier defenders. She was commissioned only because her predecessor Enterprise did not comply with the new regulations required under a complicated ratings formula. To reduce costs, Vanderbilt pilfered much of the equipment and hardware from Enterprise and borrowed expensive sails from one of his competitors. Nonetheless, she proved remarkably fast in trials, and her crew of professionals—many carried over from Enterprise—had no peers. She was favored to keep the Cup.

In a stunning development, the challenger won the first two races by narrow margins. Midway through the third race, Rainbow trailed by more than six minutes and Vanderbilt was in real danger of becoming the first American to lose the Cup. In subsiding winds, a disheartened Vanderbilt turned the helm over to his tactician, Sherman Hoyt.

With extensive racing experience in England, Hoyt knew Sopwith’s tendency to cover a competitor regardless of distance to the mark. In a brilliant bluff executed in hazy conditions, he steered to the wind causing the sails to shudder. True to form, Sopwith followed suit to keep between the defender and the finish line. Endeavour then ran into a calm patch, was forced to tack, and suddenly found itself chasing Rainbow, whose navigator knew the precise location of the finish line. Rainbow won the third race by nearly three and a half minutes.

Rainbow won again in the fourth race, narrowly and amidst great controversy when Sopwith’s protest flag was dismissed for having been raised too late. Perhaps unnerved, Sopwith lost the next race by a large margin. Fierce maneuvering at the start of the sixth race resulted in both captains raising protest flags they later refused to pursue. After a hard-fought tacking duel, the two yachts battled to a close finish, with Rainbow securing a better angle and racing across the line less than a minute ahead of her challenger. Sopwith felt he did not receive “a square deal” and declared he would not race again for the Cup. He was neither the first challenger to utter such a declaration, nor the first to have a change of heart.

Rainbow interior, crew at dinner 1934

photograph by Morris Rosenfeld and Sons

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

1984.187.69428F

R2013.1801.044

Ranger on the wind 1937

photograph by Morris Rosenfeld and Sons

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection

1984.187.80511F

R2013.1801.045

1937: Ranger defeats Endeavour II 4-0

The end of an era

Predictably, Thomas Sopwith reversed course and decided to try once more to bring the Cup home to its country of origin. He turned again to Charles Nicholson, who designed and built just about the largest boat allowed under the rules governing J-Class yachts—Endeavour II.

To design a new defender, Harold Vanderbilt approached both his longtime ally Starling Burgess and the brilliant, young, largely self-taught designer Olin Stephens, who with his brother Rod, had gained fame for creating a series of highly successful day sailers and the celebrated trans-Atlantic race winner Dorade. Burgess and Stephens agreed to work together on a contender and embarked on a series of experiments with tank testing to determine the best model.

Vanderbilt, unable to raise the necessary funds from the large syndicate he had assembled, personally financed his $500,000 creation, Ranger. With her flattened stern and bulbous stem, Ranger was criticized as a particularly ugly yacht. But those same defining features made her incredibly fast on the water, and in action, she seemed to have no weaknesses. When Nicholson viewed Ranger in drydock, he recognized her as the most revolutionary advance in design in half a century.

Vanderbilt, wishing to avoid the controversial starts of the previous Cup contest, began the first two races conservatively. Behind at the start of both, Ranger won the races by seventeen and eighteen-and-a-half minutes respectively. Annoyed at the praise heaped on Sopwith for winning the starts, Vanderbilt reverted to a more aggressive style, winning the starts of races four and five, and then apparently pulling back a bit to keep the races from being too uncompetitive. Regardless, Ranger had clearly demonstrated her superiority and is considered by many to be one of the greatest yachts in the event’s history.

The duel between Ranger and Endeavour II was the last America’s Cup competition held between the magnificent J-Class yachts. The Second World War soon dominated the lives of competitors on either side of the Atlantic and within a few years, Ranger and all but three of the other ten J’s were scrapped to make war material. The war and its aftermath caused a twenty-year hiatus for the America’s Cup races, which only resumed after economies recovered, and then, only between boats far smaller than those that had raced in the previous sixteen defenses. In 1956, a new deed was produced that established the twelve-meter class, which at approximately forty-five feet of waterline length were roughly half as long as the magnificent yachts designed by Herreshoff at the turn of the twentieth century.

Ranger’s afterguard in a relaxed moment: Owner/Skipper Harold Vanderbilt at the wheel; Navigator Zena Bliss and Mrs. Gertrude Vanderbilt seated; rigging specialist Rod Stephens with accordion; and Ranger’s co-designer Olin Stephens with arms crossed 1937

photographer unknown

Mystic Seaport, Rosenfeld Collection, image acquired in honor of Franz Schneider

1984.187.81770F

R2013.1801.047

Detail of painting, America c. 1855

Oil on canvas by James E. Buttersworth (1817–94)

Mystic Seaport

1949.3175

R2013.1801.048

America: 1851–1945

The yacht for which the America’s Cup was named has a long and colorful history. She achieved international fame by beating the fastest yachts of the Royal Yacht Squadron around the Isle of Wight in 1851. Ten days after winning, her owners from the New York Yacht Club unsentimentally sold her to a British nobleman. She raced under her new name Camilla for nearly a decade before her eventual sale to the Confederate States of America and a brief career as the blockade runner CSS Memphis. After being scuttled in 1862, the Union raised, repaired, and renamed her USS America, and she served in the blockading squadron at Charleston, South Carolina.

After the war, USS America served as a training ship at the U.S. Naval Academy, then located in Newport, Rhode Island. She raced again in the first defense of the Cup in 1870 in New York Harbor, where despite her age, she finished a respectable fourth place and ahead of the British challenger, Cambria. In 1873, the Navy sold her to former Civil War General Benjamin Butler of Boston, who had her rebuilt and refitted for competitive sailing.

After the general’s death in 1893, she fell into disrepair while berthed in Marblehead, Massachusetts. She eventually attracted the interest of some merchants who wished to use her as a common cargo ship between Cape Verde and New Bedford, Massachusetts. A group of patriotic Americans from Boston’s Eastern Yacht Club purchased a replacement ship for the merchants, restored America, and “sold” her back to the U.S. Navy for one dollar in 1921.

The Navy intermittently used America as a stationary training vessel and for exhibition at the Annapolis Naval Yard, but she was neglected and again fell into disrepair. In 1940, she was hauled out for restoration, but work was halted the next year following the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. On March 29, 1942, a blizzard dumped heavy snows and collapsed the shed where America was stored, damaging the historic yacht beyond repair. She was finally scrapped in 1945.

Benjamin Butler’s America, rebuilt, refitted, and repainted c. 1890

photograph by Detroit Publishing Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

LC-D4-22643

R2013.1805.001

Mess table from America mid to late 19th century

Solar, E. M. & Co., New Haven, CT

walnut, mahogany, bronze, brass, glass

Mystic Seaport

1975.187.21

L2013.1801.001

This mess table from America features drop leaves, a brass gimbaled lamp, and even a small freshwater tank. It may have been aboard the famous and well-appointed schooner during her historic races in 1851, or added by her eventual owner Benjamin Butler in the 1870s.

![Mayflower [and] Galatea, the start 1886](https://www.sfomuseum.org/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/07_americas_cup.jpg?itok=g8e3ReIO)

![Volunteer turning S.H. [i.e. Sandy Hook] Lightship, Sept. 27 1887](https://www.sfomuseum.org/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/08_americas_cup.jpg?itok=8XANxhzF)

![The start [Vigilant and Valkyrie II] 1893](https://www.sfomuseum.org/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/09_americas_cup.jpg?itok=DAZpZBmA)