Terminal 2

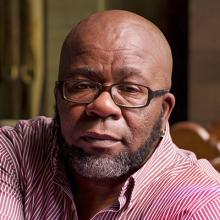

Grace, 56, Boston, MA 2013

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.001

I always felt more like girls, like women. Even when I was watching movies or television shows or reading books, the female characters were the ones that I identified with just sort of instinctively. So I knew I was born male, but I certainly was a feminine boy growing up, a gender queer boy, and was harassed and bullied and got a lot of negative attention because of that. I was assumed to be gay from the earliest get go as well, even though it wasn't talked about then in the ’60s. So, I was called all the names associated with that: sissy, faggot, fairy, all of that.

I didn't feel like I was transsexual. I didn't have that profound sense of body dysphoria that lots of transsexuals report, even though there were things that I wanted to change. So the way I understood that and was able to express that in the ’80s was maybe what we would now call gender queer. That term wasn't used then, but I lived in another gender space. I just was living in this third gender space. I didn't see it as on my way to anything. I've been lucky to have people in my life who have been supportive of me and my journey, wherever that would lead me. So it was less about giving me guidance on a specific path and more about people who have said, "Your identity's evolving, and that's a wonderful thing, and we encourage you to explore that and go with that."

I still see myself as on a journey. When I received an award a few years ago at a conference I said, "In the ’60s they called me a sissy. In the ’70s they called me a faggot. In the ’80s I was a queen. In the ’90s I was transgender. In the 2000s I was a woman, and now I'm just Grace."

Preston, 52, East Haven, CT 2016

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.002

As far back as I could remember, I've always felt like a boy. I'm the oldest of three siblings, and for a lot of years I identified as a lesbian. Back then I didn't know the word “transgender," you know. And then when I explained how I felt to somebody, they said, "Oh, transgender," and I'm like, "What does that mean?" So that's how I got to identify as transgender. When I was younger and I looked in the mirror, I saw a boy. And I remember when I came out to my parents, my mother was like, "I always knew that there was something a little different," but she didn't know what. I was born in 1964, so my parents, being born and raised down south, they had no idea whether it was transgender or gay or lesbian or anything. And so now we know what it is.

In fact, I never thought that I would actually transition while my parents were alive. I thought, “Well, it's gonna break their hearts.” That was what I was putting on myself. Even though they’ve always been the most open-minded people. But there was something about coming out as transgender to them, I was like, “Shoot, what's my mother gonna say to this?” And so I remember my partner and I, we went up and I had made an appointment with my mom and dad. I said, "I'm coming up on Saturday, please be around.” It was like two weeks prior to me coming. So for two weeks my mother was a wreck, like, "What, are you dying? What's going on? You never call and say, ‘Well, I’m coming,’ you know, you just appear.” So, we get up there, and I start crying before I can even say any words. My mother's like, “Oh my God, what's going on?” As soon as I finally got it out, then I started apologizing, you know. But my father gets up, and he comes down and kneels on the floor in front of me. He said, “That is the bravest thing that anybody could ever do.” And, of course, now I’m crying all over again, and that's when my mother said, "I knew that there was something, but I never could quite put my finger on it.”

It was fairly easy coming out to family members. I mean, most family members were like, “Well we were just waiting for you to tell us.” My mother had made a similar comment to me, and I remember feeling angry for a little bit because I was like, “But if you knew, why didn’t you say something?” I was feeling like I went through all this heartache, all these years of trying to figure it out and people knew? Like, nobody gave me a clue. Everybody was waiting for me to tell them, you know. It was crazy. It was a crazy moment, but a good one.

Hank, 76, and Samm, 67, North Little Rock, AR 2015

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.003

Samm: Hank didn’t know she was a girl until she was around eleven or twelve. She was always the boy in the family. If it was Thanksgiving, Mom and the girls cooked dinner while she and Dad went hunting. Her mother even customized her clothes. Every Easter, everybody got new blue jeans and yellow T-shirts. The girls got those blue jeans that zipped up the side, but Hank always got the fly front. The girls got a regular plain yellow T-shirt but Hank’s mother would create a pocket on hers so that it would be just like her dad’s.

Hank: But they didn’t call me “he” or “him,” they just called me Hank.

Samm: They knew that Hank was different from her sisters and Hank’s dad was excited, I guess, about having this “boy,” and Hank’s mom didn’t object. Her father would put her in boxing matches with older boys and he was really proud. Once in a while some relatives would show up and say to her dad, “Hey, you are going to make that girl funny.” And Dick would tell them to mind their own business and leave Hank alone. And that was simply it.

Hank: It was a lot like in the olden days, you know, there were a lot of people around like me and people just expected us to become “unmarried aunts” or “fancy boys” and nobody ever confronted you with it. My father would say things like, “Oh, this one will never get married.” If I heard him say that today I would say, “Oh, he’s telling them I am gay.” Only I didn’t have those words for it back then.

But when I was twelve, my parents decided that it was time for me to be a girl. This was a very strenuous thing for me because, of course, I didn’t want to be a girl. They started trying to work me into being a girl but by then my identity was already set. I was totally me. I always say, “I’m just Hank. I’m not he, I’m not she, I’m just Hank. I’m who I’ve always been.” But my father and mother decided that for my birthday they should give me some girl perfume. Perfume wasn’t something that I was familiar with. Of course, my sisters had perfume but that was for girls! And so, I was broken hearted. I mean, they could have cut me with a knife and hurt me less than saying, “Okay, now you are going to be like a girl.” Later on, when I was twenty-one, I went into the military, which took me away from them and everybody.

Samm: But there were points in the military that were very difficult. She ended up being investigated for homosexuality and examined psychiatrically, and the army ended up putting it in writing that “while she had a pretty face, she was very masculine.”

Hank: I loved the military, but I thought there was no future there for me because of the stress of the investigation. I finally went to my superior and said, “Either you are going to stop the investigation on me or you are going to charge me on something, because I can’t go on like this.” It was a very traumatic experience for me.

Samm: Eventually they brought it to conclusion and they added up all of their evidence to find that they didn’t have a thing on her.

Hank and I have been together forty-four years. We met after her time in the military, through some Chicago lesbians I had met. They threw a party every Friday night and one of those nights someone said, “There are some really fine dykes up in Western Michigan.” And then somebody said, “Road trip!” And thirty hours later, there we were in Kalamazoo. And so I found this one in Western Michigan. She was different from anybody I have ever met in my whole life and I knew that she would be in my life for the rest of my life. There was this immediate connection that would always be there. The way we are today, we started out that way.

Sky, 64, and Mike, 55, Palm Springs, CA 2017

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.004

Mike: Well, it’s not terribly complicated. I have always identified on the masculine spectrum and have used the words FTM, trans man, gay man, male to identify myself. Before I transitioned, I was with a woman in a butch/femme lesbian relationship. I identified as a leather dyke back then, and was definitely butch. In October of 1990, I went to a conference, heard of female-to-male, which I didn’t even know was possible, and went through an identity crisis. I started testosterone in February of 1991. I did not lose a lot of friends, but in the beginning it was a little rocky. It was different back then. There was no internet. You found out about groups through the backs of magazines. For a while, I refused to identify as either/or. I identified as sort of both, what we would call “queer” these days. For all intents and purposes, I still identify as queer, but my identity doesn’t come up for the most part. I get seen as male. I spend most of my time, in terms of sexualized spaces, with other gay men.

I have a unique situation wherein I have a long-term relationship with Sky, a long-term relationship with a woman who identifies as queer, and an SM relationship with another man, who I’ve been with for ten years. Sky and I have been together for twenty-five years, and my girlfriend and I have been together for fifteen years. Sky’s the first person I met who I could see growing old with, and that’s one of the reasons we’ve stayed together. We’re able to talk to each other and confide in each other. And the fact that we’re polyamorous. The freedom to have other relationships has made our relationship stronger.

One of the hardest things in terms of transitioning was the difference in personal space. When I was perceived as female, there wasn’t a lot of touching. Women don’t get into each other’s space. When two women are attracted to each other they don’t immediately put their hands on the other woman’s body. It’s not considered appropriate. Whereas the way men cruise, there’s about two seconds of eye contact, and then an approach, and either hands on your chest or hands in your crotch or some other type of immediate physical contact. I started out with a lot of insecurity in terms of my body, insecure about myself, and it has taken time to build confidence. Part of it is I lucked out: I wanted body hair, I wanted facial hair. I got it in abundance! I fit right in to the bear community; I’m short, bald, chubby, and hairy. It’s a niche for me. Realizing that someone was attracted to me, that I deserved positive interaction, that I deserved being seen that way, has taken some work. So getting used to or comfortable with that dynamic, getting comfortable with myself, was what this journey was mostly about.

I don’t have any concerns about aging, per se, because I don’t think our issues are terribly different from anybody else who’s aging. I think the greatest fear for me is the greatest fear for anybody who’s in a couple, that my partner will pass away. I’m also worried about the lack of nursing homes and long term care facilities geared toward our community. Right now, if something happened and I needed to be in a home, finding a place where I would be comfortable would be a challenge. I’m hopeful that in the next twenty years, something will change, preferably sooner rather than later.

• • • • • • • • • • • • •

Sky: I identify as a polyamorous gay trans man, primarily with a bear bent. A gay man that happens to be very different from many other gay men, but definitely polyamorous. My partner and I have been together a little more than twenty-five years, and that was the core beginning of our relationship.

My way here was as part of the women’s community. I failed miserably as a lesbian. I had sex with too many men. So it just wasn’t right. I moved to San Francisco in 1986 and became very involved in the women’s SM community. I am one of the founders of International Ms. Leather. I had to hide being a trans man for a while because I thought they would take my “card” away. Well, I finally committed and said, “This is not right.” So that’s when I began to transition and never looked back.

I also identify as a dad. My son just turned eleven last week. He’s actually my grandson; my daughter passed away six years ago from cancer. When she passed, he realized very quickly that he didn’t have a mom and he didn’t have a dad, so we let him figure out how that felt to him and what he wanted to do about it. And he decided he wanted dads. I think he’s pretty clear that we’re grandpas, but it doesn’t suit him. We let him choose names for us as well, so I’m Papa and my partner is Daddy Bear. And he always introduces us as his dads.

I’ve long thought that there’s no better school than the world. So we, the little guy and I, will hit the road full-time soon in our RV. We have lots and lots of plans. I’ve had the good fortune of being able to travel anywhere I want to – and I travel a fair amount – and not get any sorts of flack. People assume I’m either a Vietnam vet, a biker, or someone totally crazy you better not f#ck with. Either of those three things tends to work for me until I open my mouth and a purse falls out.

I live in abundance of many things: experiences, family, friends, serendipity. Living in abundance is what keeps us healthy and happy. You can’t be shackled by the minutiae of stress and expect to have a full life, and to be fearful feeds into that minutiae. Life really begins when you step out of fear. I’m gonna go where I’m gonna go. I’m gonna go see what I’m gonna see. He and I are going to have adventures without living in fear!

Aidan, 52, Burien, WA 2016

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.005

At the time of contemplating my gender and the trans element of it, I had been solidly entrenched in the dyke community. And I loved that. I felt really looked after and mentored and cared for. What they had brought into my world was a celebration of masculinity rather than a dismissal. It was like, bring it. It looks beautiful. We love it. We celebrate it. And that felt really good to me.

But what does it mean to have a trans man in lesbian space? As I would have conversations with folks I would be a little confused because I’d think, “You led me to this door and now you don’t want me to open it? You don’t want me to step through it? You brought me right here and now I’m just supposed to stare at this shut door? That doesn’t make sense. Why don’t I crack it open a little bit?” So ultimately that’s what I did. It made complete sense to me that somebody might do a gender transition, and it moved forward in what would seem to me like a trajectory. What I didn’t quite realize is that it wasn’t that way for them. My sheer presence was disruptive, and I started to push back and challenge that. I’m so impressed with so many of them because we would duke it out. We would sit there for three hours and there would be anger and tears and confusion and laughter and love.

And here I am, you know, almost twenty years later still thinking and talking about gender. You know, what is my gender? I don’t have an answer to that and I don’t need an answer. I’ve never felt fully female and I’ll never feel fully male and that’s really just fine. I feel pretty good about how I move through the world. The challenges are trying to be fully seen and received because others, of course, decide who you are. I move through the world and I don’t get a second glance. I live in a house at the end of a cul-de-sac with people who have no idea about my history. My partner has primarily identified as a lesbian in her adult life and now she’s not visible to the segment of the population that we both considered community. Not just the lesbian community, but even the broader queer community, because my transition is now a couple of decades old. You know, I continue to look more and more male. I’m older. I’m not a young pup anymore, but I still am in my heart.

Bobbi, 83, Detroit, MI 2014

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.006

I have traveled extensively. It started out when I was in the Air Force. I was the “grandfather,” or whatever you'd call it, of the drone program. I mean, I played golf with presidents, with Jerry Ford and whatnot, and I certainly have met the older Bush and younger Bush and Reagan a couple of times. I've been in the White House. I've been up and down the Pentagon, all levels. And I've also worked extensively with the CIA.

Eleven years ago was my surgery, to this date almost, and I started hormones over twelve years ago. And I really have been in the cross-dressing business or the transgender business since I was probably four or five years old. I mean, I've got that history. But I didn't know some of that history until I tracked back later in life, when I saw this more obviously in front of me. I said, "Oh, my God, this is what I was doing when I was four and five years old." And of course, it all fits into a channel. But in that day – I'm talking about being born in 1930 – that was the Great Depression. There were no words for any of this. Except that I think my mother knew, because when I asked her to teach me to knit, she did, and she'd teach me some other things that I asked if I could do, like cross-stitch and whatnot. So all the basic clues were there all along.

I think people talk in either/or terms, right? Before transition and after. But to me, it’s really development. I'm proud of both lives. I'm proud of both me’s, if you see what I'm saying. And I feel it has been a remarkable thing to have happened to a person. I’m grateful. You can't just become a woman with a knife or a pill or anything like that. It takes a whole combination in a sequence, in a formation. You've got this time span, it's a learning experience, it's a little bit of everything. It's what I call going through the internship phase, stumbling through the adolescent phase, then going through the maturity phase.

I have gone through the dating routine. That was my internship. I had to go through the Internet, go out and stumble with it and flirt, and I got pretty good at it. I kinda worked at it. I'm not bad with words. And I could play peek-a-boo on Skype. Then I finally picked up Frank. I kidnapped him from the local bar up here one afternoon, an ex-Marine. And we dated for a long time. Finally one day, it was so nice that Sunday morning with our head on the pillows, I said, "Oh, I got something to tell you." And after I told him he says, "You're better than any woman I've ever met. Now, come on, Bobbi, we can drop that." Didn't care a damn. Where I live now, I think some people know for sure who I am and don't really care. But I also don't have it written on my forehead, so there are those that don't. They just take me as another old lady, a nice old lady.

Stephanie, 64, St. Louis, MO 2014

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.007

I identify primarily as a woman and secondarily as transgender. And some days I feel rather genderless, actually. Even though I’ve transitioned, I can’t deny or completely separate myself from the past because it did happen and those memories are with me. It wasn’t until I got into my 50s that, through internet research, I discovered there was a name for all this. It was a great relief. And then, for me, it was like, “Push the throttles all the way up, we’re going full speed!” Because, you know, it was a matter of life and death at that point.

But the transition was also pretty costly in other ways. My oldest son doesn’t speak to me anymore, and he hasn’t for over five years. He’s married, and they had my grandchild almost three years ago. I’ve never been able to see the grandchild. There’s no communication, but I try to keep the door open. It’s probably the saddest part in my life. You know, there is a lot of discrimination that happens with transgender people, but the worst discrimination to me is what families do. I am just astounded by what people can do to each other, when your own family runs a sword through you.

I also experienced losses in my work life. I was a strategic account manager at a major corporation. I had big accounts like Walmart and Boeing. I was in the big leagues. When I decided to transition, I did it very carefully through Human Resources. I had it all planned out with management and thought I’d be supported. But even though I did it by the book, not long after I transitioned, there was a great deal of movement away from me. Almost immediately the people in my group, who were all men except for one, formed this wall. I remember one day very specifically when we were sitting in a morning meeting and the VP was looking around and said, “Does anyone want any bagels, donuts?” And, of course, everybody raises their hand. Then he goes, “Stephanie, how about you run over to Einstein’s and pick us up some?” And there I was, a high-level manager, being treated totally differently after I transitioned.

They eventually terminated me for lack of performance, saying I wasn’t working enough even though in reality, I was burning the candle at both ends. And they wouldn’t allow me to take a demotion, they wouldn’t help me to find a position within the company doing something else, no accommodations at all. So, I took a year off to get my head on right and to fully become Stephanie as much as I could. After a year trying to find a job I realized that my entire industry had blackballed me. I mean, literally thousands of people across the country knew what I had done. It was the talk of the industry and I was devastated that I didn’t get more support. I was crushed that I did not get job offers when I started looking. I eventually had to spend all my savings, 401K, everything, and wound up getting some little jobs here and there. I had to start doing home healthcare to make ends meet. It has been an eye-opening experience to see how you can go from making six figures to living on ten dollars an hour, all because of your gender.

Dee Dee Ngozi, 55, Atlanta, GA 2016

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.008

My middle name is Ngozi, which means God’s blessing. I was speaking on HIV and my journey with HIV in the church one night and this African minister just jumped up and said, “You’re Ngozi!” I said, “Uh, what do that mean?” and he said, “It means God’s blessing. You have God’s blessing.” So I adopted that name when I sent my name change in and then I had my last name changed to my husband’s and then we was married. I served collard greens, and ham hock, and baked cakes and he’s just as happy as a lark after the twenty-five years we’ve been together.

This coming into my real, real fullness of knowing why I was different is because I was expressing my spirit to this world. And I didn’t know how God felt about it but I believe in God and I have a deep spiritual background and I talk with the Holy Spirit constantly who’s taken me from the Lower West Side doing sex work to being at the White House.

We created the first trans ministry in our church and I sat on the “mother board” with the other mothers. One day, mother Gladys asked me to come and sit down there with them. And after we had our little meeting, after church, Miss Gladys went to do something in the office and then they surrounded me and said, “What gives you the right to be here on this mothers’ board? We don’t understand it.” I said, “Because I’m a mother to the ones you can’t love. The ones that you cannot be a mother to, that you throw out on the street every day. Those are my children. The ones you throw away.” I said, “That’s why I’m here.” You could hear a pin drop, nobody said nothing. They went on and accepted me and said, “Come on girl, sit down.”

I’d go the clinic for my HIV, I would do stuff. I’d push patients, walk them to the car, sing church songs. I was just having a ball while I was waiting for my appointment. And a guy saw me one day that had an agency, and he said, “Miss Dee Dee, you work down here?” I said, “No.” He said, “I got a job for you.” And that was God just setting me in right there in that clinic with my own desk and I was my own boss. I could go to work as myself. The first day I got on the train with my little briefcase and my little suit on with the other people that were going to work. And when I got to the front door of the clinic, the Spirit stopped me and said, “Look across the street.” I said, “Look across the street?” So I looked. Then I saw flashes of me jumping in and out of cars on that corner, and I remembered I used to run girls off that corner. That was my corner. He said, “Now look how long it took for you to cross the street.” I could have lapsed right there on that sidewalk. This had come full circle now.

SueZie, 51, and Cheryl, 55, Valrico, FL 2015

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.009

SueZie: I never thought transition would be a reality in my lifetime. After struggling for years, I finally asked Cheryl, “What about surgery?” And she looked at me and said, “Go for it.” Finally she had realized how serious I was. Every night I used to sit in the lanai smoking away, and just thinking, “Can I do it? Can I not? Can I do it? Can I not?” Every night. For years. I also had bad asthma, COPD, sleep apnea, acid reflux, migraines, you name it. But when I started going through the motions everything pretty much vanished overnight. All those illnesses, all those stresses, gone. I said to Cheryl that I felt so good I could probably give up smoking and I wouldn’t even notice. Didn't have another one.

Years of self-administering hormones caused a complication that threatened my chances for surgery. I said to Cheryl, “I’ll die as female. Nothing is stopping that surgery.” If there was a 95% chance of failure, of dying on the operating table, that was a risk I was willing to take. I could not go on how I was. My greatest challenge, it came from within. It was having the confidence to face the world out there. The perception that everyone isn’t going to accept you, it’s a little unfounded. When you first come out, you’re pretty rough. You get a few people to support you. Plenty that don’t. As you start looking better, people start changing their opinions, they swap sides. They join the winning side. And you start getting more supporters.

I don’t care what other people think. “Peripheral blurring,” that’s what I call it. I am aware but don’t pay attention to those negatives to my left and right; I only focus on the positive reactions ahead and in front. So now I go out, bold. I’m in the real high heels, and I have the striking hair. How I see it is, if you’re bold, it’s very positive. It’s not wishy-washy. When you’re positive, it builds your confidence, and of course confidence is attractive, and with attraction comes acceptance. That’s my theory on the whole thing. Bold first, stand out.

Cheryl: When we got married, I never imagined that someday my husband would become my wife. Right from the start, SueZie confided that she identified as female on the inside, but transition never appeared to be an option. But, I never had a problem with her wearing lingerie. You know, it’s just clothes. I fell in love with the person inside, and what’s on the outside is more about what they feel comfortable with. In 2009, when she said she wanted to transition, I admit I wasn’t very accepting. It was more like “What’s going to happen to the kids and what are people going to think?” At that time we weren’t strong enough to risk losing everything, including each other.

I asked her when our son Jaison was born, “Are you even happy?” Because there was no emotion. After transition, it was a total 180. Her disposition improved and our life around here got better. I saw the difference in her and how much it really affected her. I had never seen happiness come out of her eyes before. It was truly amazing. It was difficult and a learning process, because, for instance, I was always heterosexual, never a lesbian. We say I became a lesbian by attrition.

But everything was for the better and it’s working out okay. Even our intimacy has elevated. As I tell people, “I fell in love with the person, not the appendages.” I’ll always love her and we are always there for each other, deeply connected. Jaison has always known that she wears “girlie clothes,” as he calls them, so he’s good with it, too. We’re doing well. The smiles. Never had smiles before. If you’ve seen the pictures of before, you could see the sadness, there was no light in the eyes, there was no smile on the face. Now you can’t stop it.

What am I looking forward to in the future? Maybe she’ll get a little quicker on her makeup in the morning! Gosh. The future. It’s a whole new way of life. We’ve had fourteen years now, and I hope we’ve got another fourteen years ahead of us. I’m excited to see what the future’s going to hold, but also a little nervous. The unknown can be daunting, but we will face it together. I’m really looking forward to it.

Caprice, 55, Chicago, IL 2015

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.010

I’m a fifty-five year old woman of trans experience and I’m a woman of color. And my life is amazing. I am the eighth child of twenty-three. I remember back, starting at the age of three, my mother used to buy these Tonka trucks. Santa Claus would bring all the little toys and I always got the boy toys and I was not fond of them. I always played with the teapots and the baby dolls, and so she always knew, always had an inclination, and she just waited for confirmation. I had sisters that were older than me and they had birth control pills that they never took. As early as twelve, I swallowed the pills and got my little baby bruises.

I remember coming out the bathroom with the little booster bra that the girls taught me how to wear. You know, you cut the insides out so that your boobs could just grow out perky and what have you. I had the stereo up real loud, and my mother had left for work, and I came out spinning around with my bra on and I hadn’t noticed that she had come back in. She noticed the boobs and I said, “Oh Ma, I didn’t know you were here.” She says, “You’ve got raisins. I’ll see you when I get home.” And I was terrified. But when she got home from work she says, “We need to have a conversation.” She says, “Are you gay?” I said, “I think I’m attracted to guys.” She said, “You don’t like girls? And where did you get those raisins?” And I told her I took my sister’s pills.

Before trans was even labeled as trans, it was sissy. I was a sissy. But my mother knew enough to be supportive. And anything that was major that disrupted our family dynamics was brought to the dining room table. We had one of those big tables where you had to add a leaf and add chairs around it because we had twenty-three in one household. I was terrified because I had to reveal my truth to my family. A lot of them were younger than me. You know, the older ones, they had a general idea. My twin always knew and I didn’t know how to verbalize it. And I was like, “Well, you know, I’m living as a girl now.” And my mother said, “We are not going to say living ‘as’ a girl. We are going to say you are living in your womanhood, your sisterhood. It gives you power, it gives you authenticity.” It was amazing for me. And just her saying that boosted my whole confidence level.

Experience is the greatest teacher. You have to give back. I have been working in the field of social service for seventeen years. I have been an activist and advocate for trans women of color and trans-identified individuals for the majority of my life. My sisters are dying. My sisters are not being connected. And I am connected. I got connected through community. I remember when I was getting food stamps and no Medicaid, and I was buying black market hormones. But once you have it smooth, it is important you grab one of your girlfriends, one of your boyfriends, and tell them “Look baby, somebody showed me how to get through this block here, come with me and let me show you how to do it too.” My life relies upon me being able to give to my community, and my reward is when I see people take what I have given to them and do something constructive with it. I want people to say, “She showed me how to do this. She taught me how to do that.” That is my gift. My mom taught me how to open my eyes to this particular gift. God blessed me with the whole thing. I am the greatest gift I have to offer.

Louis, 54, Springfield, MA 2014

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.011

In the last few years I have seen tremendous growth in the transmasculine community. Keep in mind that in my generation, the notion of community was almost an intentional causality to the process. You were supposed to move away, never let anyone know your history, and move into isolation in order to exist. You needed to be heteronormative and have a specific way of being that fit the criteria of what this diagnosis is supposed to look like. So the notion of building community in that way… how could you if you don’t meet the standards? The notion that community is available to us is a relatively new phenomenon.

That being said, I find that the majority of trans men of color choose to live non-disclosed, low- or no-disclosure for economic reasons, for safety reasons, and for family reasons. That is a perfectly viable choice, but it does make it difficult to build community, so some of us who are fully disclosed have to serve as the conduits to connect us to each other. We have a black trans men’s advocacy site on Facebook that has almost 500 members. There is a group that just started called My Brother’s Keeper in Atlanta. When I meet other men in transition, we have a discussion about whether they want to live out and open or low- or no-disclosure. It allows me to direct them to others. I think that is critical to build community, specifically among trans men of color. There are so many other oppressions and variables that trans men and trans women of color face that it’s not as easy as hanging a rainbow flag out your window. Well, how’s that gonna work? You gonna pay my bills? Are you going to walk with me everywhere I go and be my personal bodyguard? So the notion that “out” is always better assumes a safety that many of us, especially trans women of color, cannot count on.

I’m so excited that in a relatively short slice of history, a community has grown up around me of vibrant, creative, amazing people: men, women, and others who are doing such amazing work in the realm of spirituality, sciences, art, and politics. It’s like having a gazillion nieces and nephews and other kids and being really proud of all of them.

Years and years ago when I was tiny kid I just wanted to grow up to be a husband and a father, but in that time and place it was completely impossible. So the notion that I have those things in my life now is nothing short of miraculous. And how many people in the world can say that the dream they had that was impossible, they are now living it? It is an amazing and surreal and awe-inspiring dream come true. So I am extremely grateful more than anything else, and I will continue to seek that gratitude in ways that I can and continue to be an example to people who are really struggling. The impossible is possible. Likely, maybe not. Easy, most defiantly not. But possible. So that is a joy and I will continue doing that until I kick the bucket.

Duchess Milan, 69, Los Angeles, CA 2017

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.012

I just know I’m me. I don’t think in terms of names and forms and all that. It doesn't matter. I’m just myself and that's who I am. I am at peace with myself. It is the most wonderful feeling in the world because you’re never in a hurry to get somewhere, you know, to prove to anyone that you’re who you know you are. I know who I am, and what other people think about me is none of my business. So that’s who I am. I identify as the Duchess.

I knew that I might lose family, that people might reject me. But I weighed that, and I thought, “If I lose everything and everybody, but I keep me, that's all that matters. That's all that matters, because I'm not going to live a life that I'm not happy in, for other people. Why? It doesn't make any sense.” So I put my money down and took my chances. My family accepted me. They came to accept me, and I've had kids around me, I've gone to all the weddings, all the funerals, and it's a situation that everybody just thinks of me as who I am. It's not even an issue anymore. "Oh, you mean her? Oh, that's just Auntie.”

My grandmother was a country woman, and she had a lot of sayings. I always heard all my life, “This is how it is. This is what it is. If you plant tomatoes, you're going to pick tomatoes. Okay? Don't plant bell peppers and then look for tomatoes. Okay?” And so many people do that! And then they end up with the bell peppers and say, "Well, I don't like this.” Well, of course not, honey, because you were going for tomatoes. So always go for what you know you feel!

My mother said when you die, you stand there before the light, and you say, "Was I worthy of myself to know that I have liked me?" Okay? I like me. Okay? And I will tell the whole chorus, honey, "I like me." I don't hurt anybody, I don't do anybody wrong, you know. I’ve dealt with everything I can, as much as I can. So just find that inside yourself and take time with that person. Faults, flaws, wishes, all of it, it doesn't matter. We're not going to get it all. None of us gets it all. Okay? But what we do have, we can polish. We can polish it, honey, till it blinds them.

Sukie, 59, New York, NY 2016

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.013

I was first aware of my identity when I was like six or seven years old. I always liked girls, but I never liked wearing any girls’ clothes. At that time, they used to say “lesbian” because they had no idea about trans. But ever since I was six or seven years old I lived as a boy. They used to dress me in girls’ clothes but I would go to school and change them downstairs. I grew up right here in the Bronx. We weren’t a big family, we weren’t that tight. I grew up with my mom and great-grandmother, but my great-grandmother was my caretaker. She just went along with everything. And when I finally came out, nobody said anything. That was the one thing I’m lucky about. I didn’t have a problem with that. And about ten years ago when I started hanging out with other trans people, I learned about it more. I went to my doctor, and even though my doctor didn’t know much about it, we both did research and I started testosterone, and ever since then I go to a transgender clinic. It’s really good.

In the Hispanic community, you know, a lot of cisgender men, they don’t take trans very easy. So that’s why I just make sure I’m careful. It’s really a safety issue. I don’t trust too much. Being Hispanic, I have to be more masculine. You know, like I gotta really make sure, you can’t be that soft or whatever. It’s like, “Boom, masculinity!” with some Hispanics. I was married for fifteen years, but she passed away ten years ago. Her family didn't know I’m trans. When they found out, they wanted us to break up. It was kind of rocky, but we worked it out for fifteen years. Now I’m in a relationship for the first time in ten years. We’ve been going out for three years now. Talking about marriage, but I don’t know yet.

When I first got an apartment, I moved everything in, and for some reason the landlord went through my stuff and saw a pamphlet on HIV and trans. When I came back that night, they’d changed the lock. That was a whole big deal. I called the cops, they couldn’t do anything. I took it to the Human Rights Commission, they said because it was a private house of two families, they couldn’t do anything. That was like the most horrible day, I had the two kids with me. Now I volunteer at Housing Works that has a program for people who are HIV positive. I go there like four times a week. I’ve been doing that for the past twelve years. My main occupation is outreach and peer-educator. I’m also doing the HIV Stops With Me campaign, because a lot of people don’t think trans men can get HIV. I’m about the only trans man in that campaign. I did it to let it be known. I have nothing to be ashamed of with HIV. It is what it is and if I can help other people, it’s all good.

David, 63, Hull, MA 2015

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.014

When I was five years old, I found my older brother’s first communion suit. It was a very cool looking suit, white and double-breasted, and it fit me perfectly. I wouldn’t take it off. I wore it every day. Day in and day out, until my parents got so tired of seeing it on me, they turned it into a Halloween costume as a way to get rid of it. When I was older, I played in this little rock band and one time when I was over at my friend’s house I heard his mother mention a story about a person named Christine Jorgenson who had “changed sex.” I couldn’t keep my mind on practice after that! I wanted to find out more about this person, but you couldn’t Google it, of course, and so it took me months to find it. I was finally able to piece together that this was a person who knew their gender and went somewhere and there were people who could help.

A little after my eighteenth birthday, I was thinking I was gonna have to go to Denmark or Sweden or who knows where, but I found out there was a gender identity clinic right in Cleveland, Ohio. My transition took about three years, and at that time it was very regimented with the Harry Benjamin standards of care. I worked with a wonderful group of people. They wanted to learn from me and it felt mutual. Of course, it was all still their call, everything.

I ended up finding my way to ministry years later, and I had hoped I could share my story, but that was the early ’80s with Reagan, Anita Bryant, you know, all of those wonderful souls. After I was ordained, I moved to Idaho and had two little churches. Later I moved to a church in Portland, and after many years of being terrified that my church was going to find out and throw me out into the cold, I began to break something open in myself. It just continued to grow and once that crack happened, I felt like it was time.

I was not out to my children yet, but Deborah, my wife, and I knew we wanted our children to know before it was public. So we had to figure out how to do that, and that opened the door to everything else. At this point, three of our children are very supportive and very proud of us, but two of our children have decided the stigma is too much and don’t want to be around us. It’s very painful. We’re still reeling from that.

Last year I hosted a one-day retreat specifically for transgender and genderqueer people about spiritual practices and sources of strength. I want to continue to do these retreats as a source of community building and spiritual empowerment. It was wonderful. There was one person who grew up Methodist and hadn’t been in a church in over ten years, and he reflected on how wonderful it was for him to be back in that environment. It was a really positive experience, seeing people feel welcome in that space. I am looking forward to continuing this work.

Tony, 67, San Diego, CA 2014

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.015

I was a teenager back in the ’60s. Especially in high school and around other kids, I always had a gender problem. I was born female, I lived as a female, but I’m really a man. I always knew that I was a boy growing up, but I had to keep my male side separate.

Let's see, my son was born in 1972. I was married twice, had a bad lesbian relationship because, you know, she was one of these lesbians that didn’t want to see a female becoming a man. It was when I was first married that I still had to be this female in public, but I just didn’t want to be. I hardly identified with it and I was pretending. But when everyone was out of the house, there I was in men's suits, acting out, privately.

Being diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder has helped a great deal, but I’m still fighting off the people, especially my family. I said to myself, “You know, I’m sixty-three and this has to stop. I’m going to go for it.” So at the age of sixty-three I decided that I just wasn't gonna go on living this way, living female. I was more comfortable living male and I wanted to do the whole total package. Tell the young people going through transitions to never give up. If they want the total package, never give up. I went through periods of giving up, but I had to push myself.

They say that when you go through the testosterone one of the symptoms is that you’re an adult and an adolescent at the same time. I feel that I’m still going through adolescence. I just want to do everything now as a man. This is who I am and I just want to get in everything, you know, like bungee jumping, like going on a rollercoaster again! I want to take care of and appreciate what life is offering me as a man. I’m living the life that I lost.

Alexis, 64, Chicago, IL 2014

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.016

I remember I was four years old when I first told my mother – well, no, it was actually my grandmother – that I was a girl. My heritage is Mexican and Apache, and they have very rigid binaries for gender. I mean, they just yanked away anything that they thought might be feminine. It was devastating to me. And the fact that I was Apache meant that this was never talked about in my house, because back in those days social service agencies would yank the kids and put them in Indian schools.

As I grew up, I guess you would say I was genderqueer or gender nonconforming. But when you're twenty-something and you've been on hormones – and I was 115 pounds and five foot four with hair down to my butt – it was real hard to not get attention. And men were real strange to me. On the one hand, they would call me a fag and a pervert and everything else, but then they would come on to me. And when I would tell them no, that would enrage them. They were like, "You're gonna deny me? I'm giving you a gift."

So to me, those experiences started really connecting me to women's oppression. That's when I began my feminism thing. I started to see that my oppression was similar to what my mother and my sisters were going through. I began to connect it. To this day, I still preach that women's oppression is my oppression. In terms of trans activism, I was recently talking to some of the girls that were at Stonewall back then. They're old timers like me. They look at the word "tranny" the way I do. We empower ourselves rather than let that trigger us. It's like the Dyke March. “Dyke” was also a word we took back. To me, if you're out on the battlefield, you have to be able to take the booms and the bangs and everything else and keep pushing forward.

The activism keeps me young. It really does. But I love my age, and I love when I can mentor somebody else. I love it because – and I never thought I'd say this – my age gives me a perspective that youth denied me. Because when I was seventeen, I knew everything. By the time I was thirty-five, I started figuring out that, "Well, you know just about everything." And I think by the time you get to be sixty-five, you realize how little you really know and how precious those things are that you do know.

D’Santi, 54, Santa Fe, NM 2017

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.017

I identify as a straight male, and I’ve always known. My first memory was saying, “I am not a girl. I don't want to be a girl.” All the games we played, I always played a boy. Didn’t wear dresses. Fast forward about fifty years. I meet my partner, CC, which stands for Cuauhtli Cihuatl, Eagle Woman, and she asks me, "How do I honor you? What do I call you?" She said she could see it in me. The more we talked, the more it was like, "Oh, I should be transitioning." It changed my life. She's the one that helped me realize I can be authentic and be okay with it.

I knew I was different, but I could never figure out how. I self-medicated, a lot of alcohol. I drank until I blacked out. I liked that altered state, because then I didn't have to be me. I was just one of the guys. Just identified as being gay, which I could handle, but it still wasn’t enough. I tried to date, because that's what society said we had to do, and I just couldn't do it. I could never see myself in that role, as a wife, as a mother. It just didn't fit me.

Music was big in my family. Aunts and uncles playing guitars, mandolins. We were at somebody's house every weekend, playing music. So as soon as I got old enough, I was like, "I want to learn, too." My cousins were playing, my brother was playing. It was my escape. I could just get lost in music and say anything I wanted.

In 2010, I had a nervous breakdown. I knew I was searching for something, but I had no idea what. And then I found the Aztec tradition, the Native American tradition, and I was drawn to that, so that's what I follow now. I'm a curandero. I'm a fire guardian. I embrace the two-spirit. This tattoo here is for my Mexican name, which is Ome Xiucoatl. And it translates to "The Two-Spirit Fire Serpent." I embraced the indigenous side of my bloodline and the spirituality there really speaks to me. Because to me, spirit is everywhere. It's in the plants, it's in the trees, it's in the air. The creator is everywhere. The creator is in music. I don't have to go to a building on Sundays. And the message is not about how much money you give to the church, it's not about how you identify, it's just that you be the best person you can be. That's the bottom line. My spirituality has totally shifted and I'm much happier.

People need to know they're not alone. Because that was my battle. For fifty years. I was in it by myself. I told my mom, because I didn't know how to tell her, I said, "You know I’ve never been the girly girl. Well, I just decided to embrace the maleness in me." She was like, "Okay." I go, "You're gonna see some changes in me." And she's like, "You are who you are. You don't need to change who you are, because you are who you are. But if that's what you need to do, then do it." Yeah. My Catholic mom. So I said, "Wow." Because the bottom line is she wants us happy.

I’m really excited to live my life. I just want to play more music. Spend time with my wife, the grandkids, my family. Be authentic. CC and I were talking last night because our anniversary is coming up. We've known each other for six years, so I told her I'm six years old, because that's when my life started. She helped me realize who I am. So, I am six years old. I missed the first fifty years of my life, but I'm not missing the second fifty.

Justin Vivian, 54, New York, NY 2017

Jess T. Dugan (b. 1986)

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and ClampArt, New York, NY and Turner Carroll Gallery, Santa Fe, NM

R2022.2001.018

Well, I guess I identify as trans non-binary. And I say “I guess” because those seem to be the most applicable terms in the current list of options. The thing that made me really start questioning gender was when I was a kid, and I was wearing my grandmother's clothes, and my father told me that boys don't wear those kinds of clothes, and I'm like, “Well, I'm wearing these types of clothes so either I'm not a boy or he's wrong.” At that time, I thought it was an either/or question, but now I realize he was wrong on both counts.

In my family, people seem to live a long time. My mom is eighty-three, my grandmother was ninety-two when she died, my grandfather was ninety-one. On my father's side, my grandfather was eighty-eight. So I'm prepared to live a very long life. I'm also prepared to die tomorrow. I'm not concerned about dying or whatever, it doesn't really scare me. I've seen so many people die, that process has been demystified to a certain extent.

I always knew I was trans, and I always knew that I was femme. On the gender spectrum, I am much closer to female. I didn't start taking estrogen, or as I call them, “lady vitamins,” until I was in my late forties. Part of the reason I did that was so I would have a physical and medical record of being trans. So many older LGBT people, when they become ill or if they start to deteriorate mentally and aren't able to articulate things as well, end up involuntarily, just by the assumptions of the people who care for them, being relegated back into the closet. My fear was that I would become incapacitated in some way and then be stuck in a room full of old men and I never, ever want to be an old man. That is not my jam.

I'm happy now. I have a good relationship with what's left of my family. I wish I had known when I was younger that I wasn't doing anybody in my family or my circle of friends – or myself – any favors by not being aggressive and asserting who I was from the get-go. I felt like I could be fluid enough to drift in and drift out of other peoples’ lives, and be who they were comfortable with me being, and then leave them and go somewhere else and be myself. I think that was a mistake. I felt isolated as a child because there were only certain people I could be myself around, and I feel like I carried that with me through adulthood. So, I can be myself when I'm by myself, or with a few close friends, but I feel like I should've been able to be myself with my family a little bit more and with a larger group of people, but I just didn't trust them enough to do it. It wasn't a risk that I felt like taking and I wish I had.