International Terminal

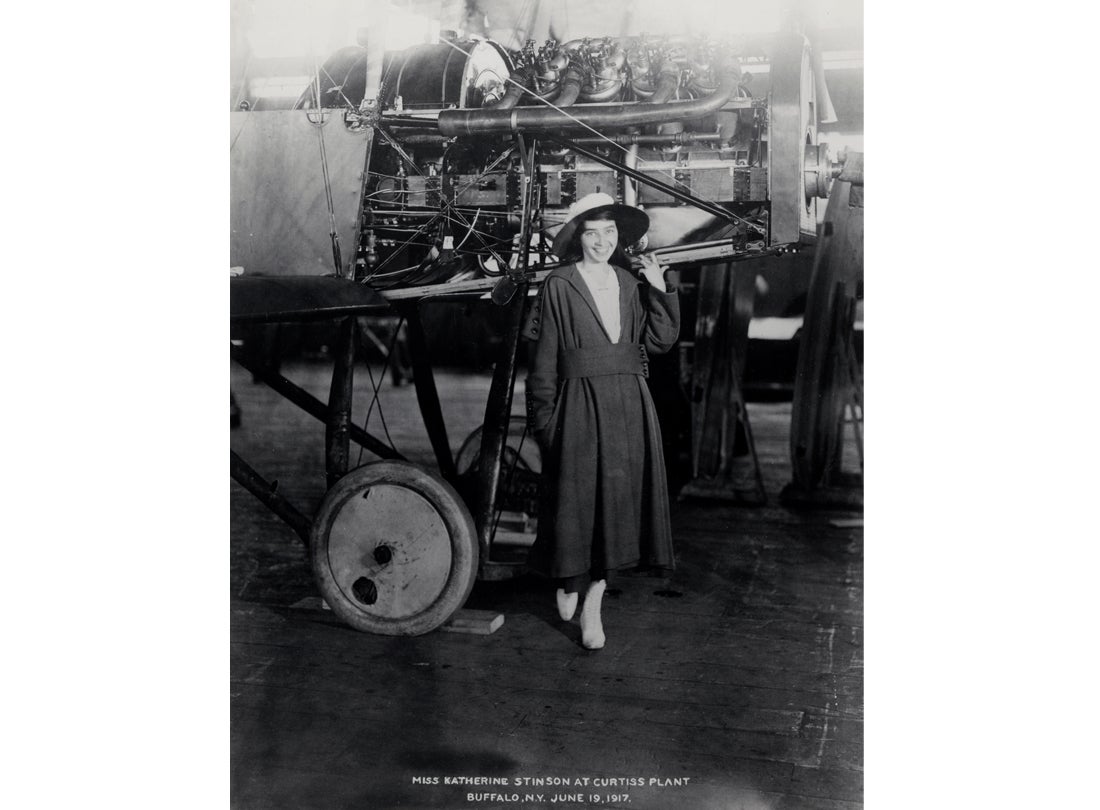

Katherine Stinson at the Curtiss Plant, Buffalo, New York 1917

photograph

Collection of the National Air & Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

86-7260

1993.10.12 a

R2020.2405.001

Katherine Stinson

Born in Fort Payne, Alabama, Katherine Stinson (1891-1977) was the fourth woman in the United States to obtain a pilot’s certification. Aspiring to become a professional pianist, she learned to fly as a means to earn money for her music education. She first flew in 1911 and was licensed in 1912 at the age of twenty-one. Referred to as the “Flying School Girl,” Stinson quickly became a star attraction at air meets and exhibitions. In 1913, she incorporated the Stinson Aviation Company with her mother Emma (c. 1870–1940). By 1915, she opened a flying school in San Antonio, Texas, with her sister Marjorie (1895–1975) and brother Edward (1893–1932), both of whom were also accomplished aviators. Edward would later establish the Stinson Airplane Company in 1920. Stinson became the first woman to perform an aerial loop and continued to perform the stunt hundreds of times without a mishap. In 1917, she was the first woman to fly in Asia when she traveled on a six-month airplane-flying exhibition tour of China and Japan. She was also the first woman to fly mail for the U.S. Postal Service. She petitioned to fly for the military during World War I but was denied due to her gender. Instead, she joined the ambulance service for the Red Cross in Europe, where she contracted tuberculosis. After the war, she moved to New Mexico to help in the treatment of her disease. Stinson continued to support the advancement of aviation and the celebration of its history throughout her life.

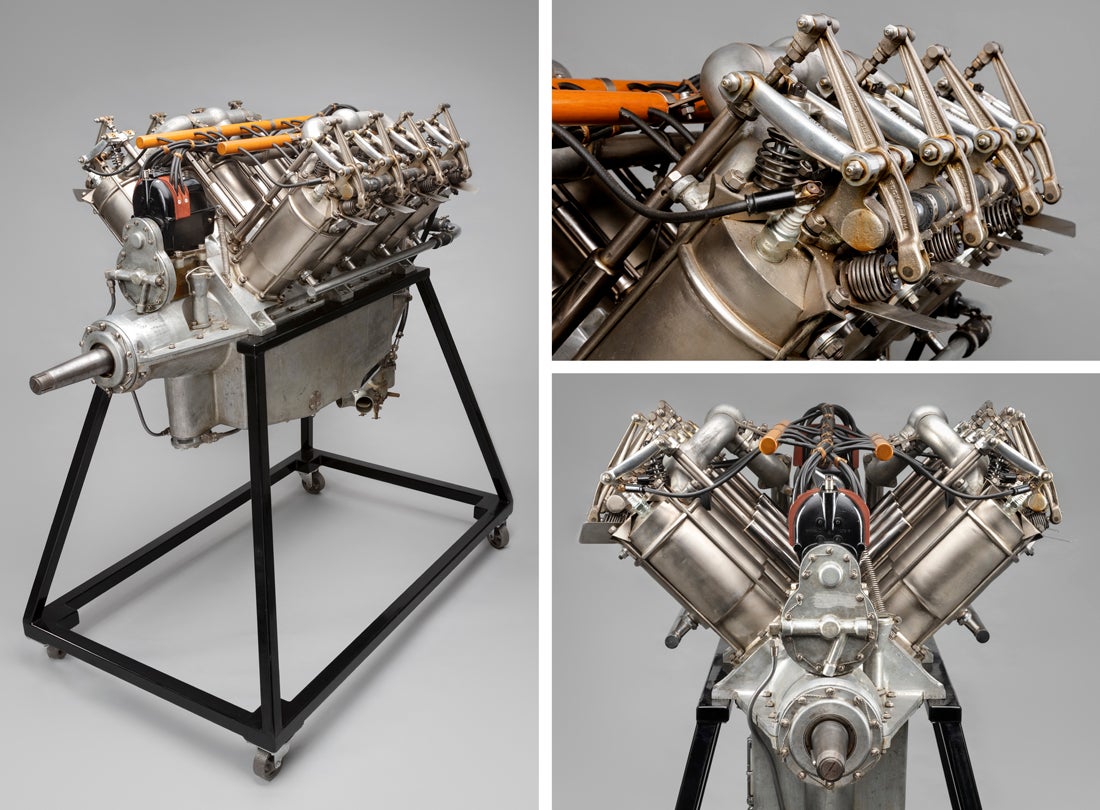

Curtiss OXX-6 V-8 aircraft engine c. 1917

aluminum, steel, rubber

Courtesy of the Frederick W. Patterson III Collection

L2020.2401.001

Curtiss Engines and the OX Series

Glenn H. Curtiss (1878–1930) started the Curtiss Company in 1902 to manufacture engines and motorcycles. In 1907, he set a world speed record of 136 miles per hour on a V-8 motorcycle of his own design, making him “the fastest man on earth.” Around 1904, he began manufacturing engines for airships. He first developed and flew airplanes in 1908 and won numerous air meets, prizes, and open challenges. These included the Scientific American Trophy for distance in 1908 and the 1909 Gordon Bennett Trophy for speed in Rheims, France. His engines provided a clear advantage. He also developed the first successful flying boats, beginning with the Model E in 1912. As Curtiss engines became larger, liquid-cooling systems were added. A V-8 series designated O+ (later tilted to become an “X”) was first produced in 1912 for the U.S. Navy. As refinements were made, a more powerful and reliable OX-5 model was developed around 1913. During World War I, the OX-5 became the first mass-produced American-designed aircraft engine in the United States. The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, formed in 1916, became a leading wartime aircraft manufacturer. An upgrade of the OX-5, the OXX-6 replaced a single magneto with two for greater dependability, and slightly larger cylinders provided an additional 10 horsepower over the OX-5 for a rated output of 100 horsepower. Later resold as government surplus in large numbers, the OX-5 and OXX-6 were among the most used American aircraft engines during World War I and well into the 1920s.

Paragon Striker propeller c. 1918

American Propeller and Manufacturing Company, Baltimore, Maryland

wood, copper, steel

Collection of Wings of History Air Museum, San Martin, California

L2020.2403.001

Wood Propellers

Aircraft propellers convert the power produced by the aircraft’s engine into thrust. Most early manufacturers produced fixed-pitch propellers from wood. Initially, they were created from single pieces of wood. As propeller technology advanced, manufacturers began to laminate thin layers of wood together. This prevented warping and enhanced strength. Most wood propellers were constructed from the preferred hardwoods of walnut, birch, oak, or mahogany. Often, a metal sheath was added to the leading edge of each blade for extra durability. This helped protect the wood from damage by rocks and other debris that was common on the dirt airstrips of the 1910s and 20s. This Paragon Striker propeller was designed for use with a Curtiss OX-5 engine and was produced of oak by the American Propeller and Manufacturing Company (APMC), of Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1909 by patent lawyer and engineer Spencer Heath (1876–1963), APMC grew to become one of the leading American manufacturers of propellers in the U.S. by the late 1910s.

The Fokker F.VIIb/3m Southern Cross and crew prior to transpacific flight 1928

Left to right in front of car: Charles Kingsford Smith (pilot) Charles Ulm (copilot), Harry Lyon (navigator) and James Warner (radio operator)

photograph

Collection of San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

MOR-0759

R2020.2404.001

The Transpacific Flight of the Fokker F.VIIb/3m Southern Cross

Flown by Australian pilots Charles Kingsford Smith (1897–1935) and Charles Ulm (1898–1934), with navigation and radio operations performed by American crew members Harry Lyon (c. 1885–c. 1963) and James Warner (1891–1970), the Southern Cross was the first aircraft to complete a transpacific crossing from North America to Australia. Introduced in 1925, and initially conceived as a single engine transport, the Fokker F.VII was later redesigned as a trimotor powered by three Wright J-5 Whirlwinds. By 1927, the Fokker F.VII/3m had achieved a reputation for remarkable endurance, which included the transatlantic flight of the America and the transpacific flight of the Bird of Paradise from Oakland, California, to Wheeler Army Airfield on the Hawaiian island of O'ahu. The Southern Cross was initially acquired as a salvaged aircraft from explorer George Hubert Wilkins (1888–1958) after it was flown in the 1926 Detroit News Arctic expedition. Reequipped with new Wright J-5 engines and the latest ground-adjustable Micarta propellers supplied by Westinghouse, the plane was based and tested at Mills Field Municipal Airport of San Francisco (later SFO). The airplane departed from Oakland, California, on May 31, 1928, and flew first to Wheeler Army Airfield, O'ahu, then to Suva, Fiji, and continued on to Brisbane, Australia, landing on June 9th. The three-stage trip covered a total distance of 7,200 miles in ten days at an average speed of ninety miles per hour. Over this long, transpacific route, the Wright engines performed exceptionally well with no significant problems or incidents.

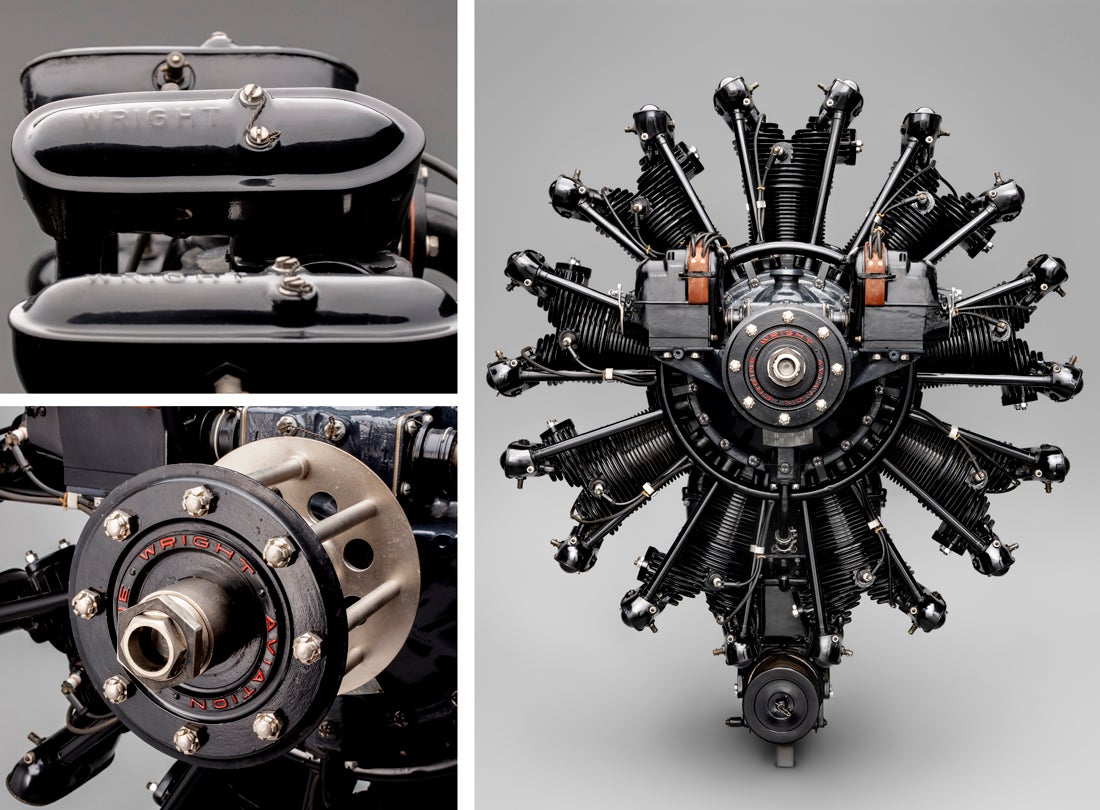

Wright J-5-A R-790 Whirlwind radial aircraft engine 1929

Manufacturer’s number 13638

Wright Aeronautical Corporation, Paterson, New Jersey

aluminum, steel, rubber, phenolic

Courtesy of the Frederick W. Patterson III Collection

L2020.2401.002

The Wright J-5 Whirlwind, Built for Endurance

The development of the Wright J-5 Whirlwind began in the early 1920s with the Lawrance Aero-Engine Corporation, a company founded in 1917 by Charles L. Lawrance (1882–1950). Lawrance produced a highly reliable and durable air-cooled, nine-cylinder, radial engine for the U. S. Navy called the J-1. Unable to meet production demands, the Navy encouraged the Wright Aeronautical Corporation to absorb Lawrance’s company. After steadily refining his engine for Wright Aeronautical, in 1924, Lawrance became president of the company and introduced the improved J-4 model, the first of the “J” series to be named “Whirlwind.” Further improvements included a breakthrough cylinder design by English engineer Samuel D. Heron (1891-1963), which comprised separating the cylinders with more space, and substantially widening the cylinder cooling fins. The rocker arms and pushrods were also enclosed, a first for radial engines built in the U.S at this time. This created a more durable engine that ran cool and lean for long durations before needing lubrication and maintenance. Introduced in 1925, the new engine was named the J-5 Whirlwind and quickly revolutionized the aviation industry. Charles A. Lindbergh’s (1902–74) Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis was specifically designed around the J-5 engine. Lindbergh’s 3,600-mile transatlantic flight in 1927 established the J-5’s reputation for long-distance reliability. Shortly after, Whirlwinds were used on the 2,400-mile, record-setting nonstop flight from Oakland, California, to Hawai’i by U.S. Army Air Corps pilots Lester J. Maitland (1899–1990) and Albert Hegenberger (1895–1983) in the Fokker C-2 tri-motor Bird of Paradise. The next year, the J-5-equipped Fokker F.VIIb/3m Southern Cross was piloted by Charles Kingsford Smith (1897–1935) and Charles Ulm (1898–1984) on a 7,200-mile, three-stage, transpacific route from Oakland, California, to Brisbane, Australia.

Westinghouse Micarta propeller and ground adjustable hub late 1920s

Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Bakelite plastic, canvas, metal, decals

Courtesy of the Monte Chase, Not Plane Jane Propeller Collection, Mandan, North Dakota

L2020.2402.001

Micarta Propellers

Micarta is a plastic compound first developed around 1910 by George Westinghouse (1846–1914). Initially, it was fabricated by interleaving layers of Bakelite plastic with either paper or fabric and formed into a desired shape in a mold with heat and pressure. The material was used in a broad range of products requiring a high degree of durability. As early as 1918, the Westinghouse Company was producing Micarta propellers for the U.S. Army. By the late 1920s, Westinghouse began producing single Micarta props that could be attached to a two-bladed metal hub. The hub was designed to be pitch-adjustable on the ground. Micarta propellers became well-known after the 1927 nonstop flight of the Fokker C-2 tri-motor Bird of Paradise from Oakland, California to Wheeler Army Airfield on the Hawaiian island of Oʻahu. Seeking a propeller that was robust enough to handle a flight from California to Australia, Charles Kingsford Smith (1897–1935) and crew chose Micarta propellers, which were attached to the three Wright J-5 Whirlwind engines of the Fokker F.VIIb/3m Southern Cross. After this flight, the reputation of Micarta’s strength grew worldwide, and Westinghouse highlighted these two famous flights in promotions for Micarta and Micarta propellers.