International Terminal

State Bird

California quail (Callipepla californica)

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CAS ORN 92565

L2015.0703.019

The California quail, designated the state bird in 1931, is a hardy, stout bird found in California and the Northwest. The California quail’s topknot is actually a cluster of six overlapping feathers. California quails have adapted to living in arid environments and can usually acquire adequate moisture from insects and succulent vegetation. Although during heat waves, they must find water to survive. California quail prefer walking to flying and spend most of their time on the ground in search of food. These birds are surprisingly fast runners despite their short legs.

The California quail, designated the state bird in 1931, is a hardy, stout bird found in California and the Northwest. The California quail’s topknot is actually a cluster of six overlapping feathers. California quails have adapted to living in arid environments and can usually acquire adequate moisture from insects and succulent vegetation. Although during heat waves, they must find water to survive. California quail prefer walking to flying and spend most of their time on the ground in search of food. These birds are surprisingly fast runners despite their short legs.

State Mineral

Gold Au

Amador County and Tuolumne County

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CAS 17, 19.2, 19.3

L2015.0708.052, .054, .055

California is home to many rare and interesting minerals. Almost one thousand different mineral species are known to occur in the state, some of which have not been found anywhere else in the world. California’s geologic diversity includes many important ores and economic minerals including gold, the most famous and probably the most influential mineral found in California. First discovered at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma in 1848, the mineral sparked the Gold Rush of 1849 in California bringing droves of fortune seekers to the state. The population expanded rapidly—in San Francisco alone it increased from 1,000 in 1848 to over 20,000 by 1850.

Gold forms naturally underground and is brought to the surface by geologic forces. In California, it is found in lode deposits, where it can be removed from the rocks where it formed, and in alluvial deposits, where erosion by water, ice, and wind has concentrated it. Nuggets are rounded or flattened pieces of gold found in sediments that gradually collect in riverbeds. This precious metal is very dense, soft, and does not corrode.

Basket star (Gorgonocephalus eucnemis)

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CASIZ 178866

L2015.0701.029

Invertebrates, animals lacking a backbone, account for most of California’s deep-sea life. Modern technological tools such as ROVs (Remote Operating Vehicles) allow scientists to explore the deeper waters of California where cold-water corals and sponges provide ample vertical habitat for fish and other creatures of the deep. The basket star, a distant relative of starfish, has a mass of twisting and branching arms covered by tiny, sharp hooks and spines that allow the creature to capture prey. They are able to easily regenerate limbs when they become broken.

Invertebrates, animals lacking a backbone, account for most of California’s deep-sea life. Modern technological tools such as ROVs (Remote Operating Vehicles) allow scientists to explore the deeper waters of California where cold-water corals and sponges provide ample vertical habitat for fish and other creatures of the deep. The basket star, a distant relative of starfish, has a mass of twisting and branching arms covered by tiny, sharp hooks and spines that allow the creature to capture prey. They are able to easily regenerate limbs when they become broken.

Giant sea bass skull (Stereolepis gigas)

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CAS 214927

L2015.0706.001

The giant sea bass, the largest bony fish to inhabit the California coast and its offshore islands, lives in shallow, rocky reefs. A native of the eastern North Pacific Ocean, it ranges from Humboldt Bay to the tip of Baja and the northern Gulf of California. The giant sea bass may grow up to seven feet long and weigh several hundred pounds. This slow-growing fish reaches maturity at eleven or twelve years of age, at a weight of fifty to sixty pounds, and may live as long as seventy-five years or more. In his 1910 publication The Channel Islands, conservationist Charles F. Holder describes a specimen taken from the Gulf of California that weighed 800 pounds. Adults display a dark brown to black hue with dark spots dotting their bodies. Scientists believe they possess the ability to alter their spot pattern at will to blend in with their surroundings. The full-grown carnivorous fishes’ diet varies from Pacific mackerel to shrimp, small sharks, crabs, and squid.

The giant sea bass, the largest bony fish to inhabit the California coast and its offshore islands, lives in shallow, rocky reefs. A native of the eastern North Pacific Ocean, it ranges from Humboldt Bay to the tip of Baja and the northern Gulf of California. The giant sea bass may grow up to seven feet long and weigh several hundred pounds. This slow-growing fish reaches maturity at eleven or twelve years of age, at a weight of fifty to sixty pounds, and may live as long as seventy-five years or more. In his 1910 publication The Channel Islands, conservationist Charles F. Holder describes a specimen taken from the Gulf of California that weighed 800 pounds. Adults display a dark brown to black hue with dark spots dotting their bodies. Scientists believe they possess the ability to alter their spot pattern at will to blend in with their surroundings. The full-grown carnivorous fishes’ diet varies from Pacific mackerel to shrimp, small sharks, crabs, and squid.

Commercial fishing for giant sea bass began in Southern California around 1870; sport fishing commenced around 1895. By the 1950s, overfishing of the giant sea bass caused its population to drastically decline. In 1982, the state banned commercial and sport fishing of the species. As a result, the giant sea bass population continues to make a slow recovery. Scuba divers report frequently seeing the fish along Catalina and Anacapa Islands.

Heteromorph ammonite (Crioceratites latum)

Cretaceous age (145–66 million years ago)

Cottonwood District, Shasta County

Collected, prepared, and donated by C. Schuchman

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CAS 70633

L2015.0708.002

Over the last 200 million years, the area now called California was often underwater for long periods. As a result, many of the fossils found in the state are the remains of marine organisms. Ammonites, the largest group of ancient cephalopods, are among the most common fossils found worldwide. Ammonites are closely related to modern squid and chambered nautilus. These animals had a shell that looked like a snail, but the animal inside had flexible arms and a siphon tube, like a squid. Ammonites became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, about sixty-five million years ago. California has important and highly diverse ammonite fauna, and the California Academy of Sciences’ houses a renowned collection of these fossils.

Over the last 200 million years, the area now called California was often underwater for long periods. As a result, many of the fossils found in the state are the remains of marine organisms. Ammonites, the largest group of ancient cephalopods, are among the most common fossils found worldwide. Ammonites are closely related to modern squid and chambered nautilus. These animals had a shell that looked like a snail, but the animal inside had flexible arms and a siphon tube, like a squid. Ammonites became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, about sixty-five million years ago. California has important and highly diverse ammonite fauna, and the California Academy of Sciences’ houses a renowned collection of these fossils.

Brown pelican and skeleton (Pelecanus occidentalis)

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CAS ORN 98069, CAS ORN 98069

L2015.0703.031, .032

One of the most distinctive birds in California, the brown pelican resides along the Pacific Coast from British Columbia, Canada, to Nayarit, Mexico. These stocky birds may live up to forty years and have a wingspan of over six-and-a-half feet. The pouch suspended from the pelican’s bill can hold up to three times more than its stomach. These strong swimmers require up to four pounds of fish per day. On the Pacific Coast, pelicans commonly eat anchovies and sardines. With their extremely sharp eyesight, they are able to spot small schools of fish from as high as sixty feet in the air. They can perform spectacular headfirst dives from twenty to sixty feet in the air in pursuit of prey. Before swallowing their meal, they point their beaks downwards to drain the water—up to two gallons—from their pouches. They then tip their beaks up to swallow the fish headfirst, while gulls and terns may hover closely in an attempt to snatch prey directly from their beaks.

One of the most distinctive birds in California, the brown pelican resides along the Pacific Coast from British Columbia, Canada, to Nayarit, Mexico. These stocky birds may live up to forty years and have a wingspan of over six-and-a-half feet. The pouch suspended from the pelican’s bill can hold up to three times more than its stomach. These strong swimmers require up to four pounds of fish per day. On the Pacific Coast, pelicans commonly eat anchovies and sardines. With their extremely sharp eyesight, they are able to spot small schools of fish from as high as sixty feet in the air. They can perform spectacular headfirst dives from twenty to sixty feet in the air in pursuit of prey. Before swallowing their meal, they point their beaks downwards to drain the water—up to two gallons—from their pouches. They then tip their beaks up to swallow the fish headfirst, while gulls and terns may hover closely in an attempt to snatch prey directly from their beaks.

Brown pelicans began disappearing from North America beginning in the late 1950s due to pesticides, such as DDT. The species was declared endangered in 1970 under the Endangered Species Conservation Act, the precursor to the current Endangered Species Act. Since then, the species has made a remarkable recovery and is no longer endangered. An estimated 620,000 brown pelicans are now thought to inhabit the Pacific Coast, Gulf Coast, and Florida.

Black, white, pink, green and threaded abalone (Haliotis)

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CASIZ 105559, 203224, 71109, 203222, 173160

L2015.0701.031, .032, .033, .034, .037

The genus name for abalone, Haliotis, translates as “sea ear.” Abalone shells display a great variety of exterior colors among species, with all of them showcasing beautiful iridescent (mother of pearl) interiors. Hidden beneath a single shell, the abalone’s uses its huge, muscular foot to attach itself to rocks upon which the snail slowly crawls to graze on marine algae. Eight species of this large, edible mollusk inhabit California: red, flat, green, pink, pinto, black, white, and threaded abalone.

At one time supporting a thriving commercial and recreational fishery, abalone populations in California are currently imperiled. Over-fishing and disease have taken the greatest toll on populations, resulting in U.S. federal listing of the black and white abalones as endangered and the pinto, green, and pink abalones as “species of concern.” Only the red abalone, the largest of all abalone species, may be harvested for sport. Commercial fishing is prohibited. Despite strong fishery regulations, an active black market persists for poached abalone. Changes in environmental conditions as our climate is altered may also have a large impact on California abalone populations. Stronger protection will be critical to supporting populations of sustainable size so that these important marine grazers may remain an integral part of our coastal ecosystem.

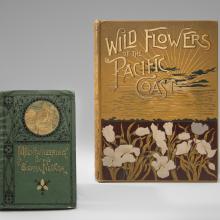

Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada 1872 | Wild Flowers of the Pacific Coast 1887 |

Approximately 6,000 species of plants grow within California’s rich and varied landscape—from native flowering plants, to conifers or cone-bearing plants, and ferns. The great diversity of climate, soils, and topography within the state has resulted in approximately 1,400 endemic plant species in the region. Some of these plants originated millions of years ago while others are of far more recent origin. At one time in the geological history of California, the state had a mild, wet climate with abundant rainfall throughout the year. During the Pliocene age (5.3 to 2.6 million years ago), the summer season became longer, warmer, and drier. Many plant species rapidly evolved in order to survive in this new climate—while others became extinct.

Approximately 6,000 species of plants grow within California’s rich and varied landscape—from native flowering plants, to conifers or cone-bearing plants, and ferns. The great diversity of climate, soils, and topography within the state has resulted in approximately 1,400 endemic plant species in the region. Some of these plants originated millions of years ago while others are of far more recent origin. At one time in the geological history of California, the state had a mild, wet climate with abundant rainfall throughout the year. During the Pliocene age (5.3 to 2.6 million years ago), the summer season became longer, warmer, and drier. Many plant species rapidly evolved in order to survive in this new climate—while others became extinct.

Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus)

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CAS ORN 92475

L2015.0703.023

California is home to an extremely diverse concentration of birds, with more than 600 species of birds residing within its borders. California contains 147 Important Bird Areas, essential habitat that must be protected to sustain the state’s bird populations. California supports habitat for resident breeders and seasonal visitors, as well as those birds passing through on migration to and from South America and Canada.

California is home to an extremely diverse concentration of birds, with more than 600 species of birds residing within its borders. California contains 147 Important Bird Areas, essential habitat that must be protected to sustain the state’s bird populations. California supports habitat for resident breeders and seasonal visitors, as well as those birds passing through on migration to and from South America and Canada.

The great horned owl, found across the United States is the second largest owl in California, with a length of about twenty inches. The “horns” of the owl are actually only feather tufts. This powerful hunter can prey upon birds and mammals larger than itself and also dines on smaller fare such as scorpions, mice, and frogs.

Red diamond rattlesnake skeleton (Crotalus ruber)

Riverside County

Courtesy of Ray Bandar

L2015.0702.001

Herpetology entails the study of reptiles and amphibians. California reptiles—scaly creatures that breathe through their lungs and lay eggs on land—include turtles, lizards, and snakes. California amphibians—limbed vertebrates that live in moist habitats and breathe through lungs, skin, gills, or a combination of all three—include salamanders and frogs. Most reproduce by laying eggs in or near water.

Herpetology entails the study of reptiles and amphibians. California reptiles—scaly creatures that breathe through their lungs and lay eggs on land—include turtles, lizards, and snakes. California amphibians—limbed vertebrates that live in moist habitats and breathe through lungs, skin, gills, or a combination of all three—include salamanders and frogs. Most reproduce by laying eggs in or near water.

The majority of these species pose no threat to humans. Even the nine types of venomous rattlesnakes that inhabit the state do not attack, but instead react to feeling threatened or startled. Snakebites, however, rarely result in fatalities as the rattlesnake’s toxic venom is intended for prey. The snakes use their camouflaged color and pattern to blend into their surroundings. This allows them to hunt by sitting still and waiting for their warm-blooded prey to pass close enough for the snake to strike it. Sometimes a passing human, mistaken for food, will instead be struck.

Black bear skull (Ursus americanus) | Mountain lion skull (Puma concolor) | Coyote skull (Canis latrans) |

The coyote, a member of the dog family, is one of several different types of wild dogs found in North America. In California, scientists observed coastal populations of coyotes consuming seal meat. Suspecting that this was not always the case, researchers analyzed much older coyote skulls. Based on the chemical composition of the bone in these skulls, they determined that seal meat is a relatively new food item for coyotes. To understand what might have caused this change, they also analyzed the skulls of grizzly bears and found clear signs of seal-meat consumption. Only after grizzlies became extinct, the researchers concluded, did coyotes begin to consume this rich food source.

The coyote, a member of the dog family, is one of several different types of wild dogs found in North America. In California, scientists observed coastal populations of coyotes consuming seal meat. Suspecting that this was not always the case, researchers analyzed much older coyote skulls. Based on the chemical composition of the bone in these skulls, they determined that seal meat is a relatively new food item for coyotes. To understand what might have caused this change, they also analyzed the skulls of grizzly bears and found clear signs of seal-meat consumption. Only after grizzlies became extinct, the researchers concluded, did coyotes begin to consume this rich food source.

Although the grizzly bear is now extinct in California, black bears remain extant in mountainous areas of the state. They are the only species of bear in California and one of three bear species in North America. Males typically weigh around 300 pounds.

Two species of wild cats also inhabit the state: the bobcat and the mountain lion. Mountain lions inhabit about half of the state of California, generally wherever deer live close by. These powerful, solitary creatures generally hunt alone at night. Similar to mountain lions, though smaller in size, bobcats are found throughout the state and generally prey upon smaller mammals such as rabbits.

American mastodon lower jaw (Mammut americanum)

Late Pleistocene age (about 10,000 years ago)

California

Collection of the California Academy of Sciences

CAS 61494

L2015.0708.020

Over many millions of years, a huge diversity of organisms have lived in what is now California. They left behind evidence of their existence in many forms; from bones to petrified trees and footprints. Most of the fossils found in the San Francisco area are either marine animals of the Miocene age or younger (less than twenty million years old) or terrestrial vertebrates of Pleistocene age (less than two million years old).

Over many millions of years, a huge diversity of organisms have lived in what is now California. They left behind evidence of their existence in many forms; from bones to petrified trees and footprints. Most of the fossils found in the San Francisco area are either marine animals of the Miocene age or younger (less than twenty million years old) or terrestrial vertebrates of Pleistocene age (less than two million years old).

During the late Pleistocene age, the American mastodon, a distant relative of modern elephants, occupied many parts of continental North America, including California.