International Terminal

Display drawer of camouflage insect specimens

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.042

Camouflage

Insects are a favorite food of birds, lizards, rats, mice, and even other insects. Because of this, insects have evolved many strategies to avoid getting eaten. One strategy, called crypsis or camouflage, is to hide in plain sight by blending in with the background. Insects do not have the ability to change their colors to blend in with their surroundings like a squid or an octopus. Instead, they evolved to have color patterns that are similar to the surfaces they inhabit, such as leaves and tree bark. A common theme in camouflage is broken lines or color mosaics. Visual predators, including birds, can learn to spot large areas of the same color, but have a harder time when these areas are interrupted by dashes and splashes of other colors. In addition, very few surfaces in nature have large areas of one color. In a white box, these insects seem very colorful and easy to spot. But on their natural substrates in the wild they virtually disappear.

Stick insects, as their name implies, resemble sticks, twigs, or branches, while leaf insects look surprisingly like leaves. Together, these herbivores belong to the order Phasmatodea, mimicking vegetation to disappear from view. Even the eggs they deposit come in disguise, typically resembling the seeds of certain plants.

Display drawer of ladybug (Coccinellidae) specimens

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.053

Ladybugs

Ladybird beetles, also known as ladybugs, all belong to the beetle family Coccinellidae. Ladybugs come in a variety of colors and sizes. Brightly colored species (like orange and black) are toxic—they exude a small, yellow drop of hemolymph (insect blood) from their leg joints that tastes bad to predators, such as birds and lizards, who can see color. Ladybugs are best known as voracious predators of aphids and other garden pests. Gardeners often buy clusters of ladybugs to control such pests, as a single ladybug might eat up to five thousand aphids in its lifetime. Larvae (immature stages) of ladybugs look like tiny, fuzzy alligators and are also predators.

People have moved many species around the world to help control pest insects. This practice is called Classical Biological Control or Biocontrol. The first modern day success story of biocontrol was the introduction of the Vedalia beetle (Rodolia cardinalis Mulsant, 1850), a species of ladybug, from Australia into California in 1888 to control cottony cushion scale, a major insect pest of oranges and other citrus trees. Another species, the convergent ladybug (Hippodamia convergens Guérin-Méneville, 1842), is collected in vast quantities in California and shipped around the world for pest control.

Cockchafer beetle (Melolontha melolontha) model 1881

Made by the firm of Dr. Louis Thomas Jérôme Auzoux (1797–1880)

Paris

papier mâché, paint, adhesive

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.001

Cockchafer Beetle

The cockchafer beetle (Melolontha melolontha Linnaeus, 1758) is a well-known plant pest in Europe, and one of the first beetle species named by Carl von Linné (a.k.a. Linnaeus), the Swedish biologist who created the binomial system for naming species. This papier-mâché model was made by the manufactory of French surgeon Dr. Louis Auzoux in 1881 as a teaching tool for entomology students. All of the internal and external organs are labeled with their proper names in a style he called anatomie clastique (“broken in pieces”). Auzoux created similar models of humans, horses, and other animals.

Display drawer of scarab beetle (Scarabaeidae) specimens

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.024

Scarab Beetles

Dung beetles, June bugs, chafers, and scarabs all belong to the beetle family Scarabaeidae. They all have lamellate antennae, which means the ends of their antennae can spread like fingers. Goliath beetles are the largest insects on Earth in terms of body mass. Some species, such as rose beetles and chafers, can be abundant pests in gardens, feeding on roots as larvae and on leaves and flowers as adults. Dung beetles and other detritivores are responsible for recycling nutrients and preventing animal waste from building up and breeding pest flies. In places where cows and other large mammals are not native, dung beetles have been purposely introduced to help control their waste.

Egyptians were fascinated by adult scarabs (Scarabaeus sacer Linnaeus, 1758) rolling balls of dung and burying them in the ground, just as the sun rolls across the sky and then disappears beneath the horizon until the next day. Ancient Egyptians also observed how scarabs suddenly realize that they have wings that allow them to fly off and explore. In ancient Egypt, the scarab beetle was a symbol of rebirth and transformation used on seals, amulets, and jewelry, and also appeared on their god Kheper, who has a scarab head. Another genus is named Sisyphus for the mythological Greek king whose punishment for thinking he was more clever than Zeus was to forever roll a rock up a hill.

Display drawer of blue and green butterflies (Rhopalocera) and colorful beetles (Coleoptera)

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.045

Structural Color

Some insects are brightly colored while others appear dull or drab. Either way, just like melanin in people, insects have pigments that give them their colors (black, brown, red, orange, yellow, etc.)—with the exception of blue and some shades of green. Blue pigments are incredibly rare in nature. Just as a prism breaks light into the colors of the rainbow, so too do nano-structures on the surface of insects. In some cases, these nano-structures resemble spruce trees. The different wavelengths (colors) of light bounce around within these nano-structures and interfere with each other, allowing only the blue wavelengths to escape. In other cases, light refracts within very thin layers on the surface of the insect allowing only blue to escape. For butterflies, these structures are part of the microscopic scales that cover their wings and bodies. For instance, the iridescent green of the emerald swallowtail (Papilio palinurus) displayed in the photograph above, is a result of blue and yellow visible reflections producing the perception of green when mixed together. For beetles and many other insects, these nano-structures are layered upon their exoskeleton. These nano-structures are also responsible for the blue feathers on birds and the blue irises of blue-eyed humans.

Display drawer of Orthopteroid specimens

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.051

Grasshoppers, Crickets, and their Relatives

Roaches, crickets, grasshoppers, and mantids all belong to the superorder Orthopteroidea and share something in common—they do not have a pupal stage like butterflies and beetles. Instead, young grasshoppers and roaches, called nymphs, look like adult grasshoppers and roaches, but without wings. The wings begin to develop on the outside of the body in older nymphs, rather than inside a pupa.

Crickets and katydids are well-known for the “songs” or chirps they produce by stridulation—that is, rubbing the “scraper” found at the base of one wing across a series of ridges or “file” on the other wing. These vibrations carry through the wings which amplify the sound. The frequency of the chirps fluctuates with temperature—warmer crickets chirp faster. To approximate the temperature in Fahrenheit, count the number of chirps in fourteen seconds and add forty. Some grasshoppers sing by rubbing a file on their hind leg against a thickened ridge on their front wing. Jerusalem crickets, by contrast, make sounds by drumming their abdomen on the ground. Males of these various species use these “songs” to attract females or ward off other males from their territory. Crickets have “ears” on their front legs, while grasshoppers have them on their abdomen, and mantids have one on the middle of their chest between their hind legs.

Display drawer of butterfly and moth (Lepidoptera) specimens

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.047

Butterflies and Moths

Butterflies are a type of moth. They evolved from moth ancestors around 70 million years ago. Butterflies and moths are covered in microscopic scales, like the overlapping scales on fish. Each of these scales can be differently colored—together forming the mosaic patterns we see on their wings and bodies. We most often think of butterflies as brightly-colored day flyers, visiting flowers in the sunshine, and moths as dull-colored, nocturnal creatures. But there are many brightly colored moths that fly during the day, some mimicking bees and wasps. Likewise, there are dull-colored butterflies that prefer the shade of the forest. The Madagascan sunset moth (Chrysiridia rhipheus) illustrated in the photograph to the left is arguably the most striking of the daytime-flying moths.

One way to tell butterflies and moths apart is by the antennae. Butterflies have an inflated segment at the end of their thread-like antennae. Moths have a great diversity of antennae—hairy, feathery, thick, or thread-like, but no inflated segment at the end. Like all insects, the antennae are lined with chemical sensors to help them find food and mates. The large, feathery antennae of male giant silk moths allow them to detect the pheromones (scent) of females from miles away.

Display drawer of bee, wasp, and ant specimens (Hymenoptera)

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.048

Bees, Wasps, and Ants

Bees, wasps, and ants all belong to the order Hymenoptera, meaning membranous wings. Most conspicuous and well-known are social species, including honey bees, yellowjacket wasps, and ants. These insects live in societies with overlapping generations and complex visual and chemical communication systems. For example, honey bees do a “waggle dance” to communicate the distance, direction, and quality of nectar and pollen resources. Most bees, however, are solitary. They provision each egg with just enough pollen and nectar to grow to adulthood, and then fly away forever. When foraging among flowers, bees accidentally drop pollen, which pollinates the plant. Nearly 4,400 different species of bees inhabit North America, and more than 20,000 species of bees exist worldwide. Many wasp species are parasitoids. Whereas predators kill and eat their prey and parasites feed without killing their hosts, parasitoid larvae feed on or inside their insect host for days or weeks while it is alive, eventually killing it before emerging as adults. Because many parasitoids prefer very specific prey species, they are often used to control pests. Other wasps are herbivores, such as sawflies that feed on leaves, needles, and wood. Gall wasps cause plants to grow tumors where the wasps’ larva develops protected from the outside world.</p>

Wasp (Vespula vulgaris) sculpture 2008

Gar Waterman (b. 1955)

New Haven, Connecticut

steel, copper, nickel plate

Courtesy of the artist

L2019.0402.001

Insects in Art

From humble ants to dragonflies and zebra swallowtails, insects have captured the imagination of artists and poets alike. Whether buzzing through the air, clinging to rocks in a stream, or rustling through the undergrowth, insects abound. However, apart from the quintessential butterfly, the intricate beauty and delicate features of most insects are overlooked due to their small size. Artist Gar Waterman brings this magnificence to life with this wasp sculpture. Its long legs and steel construction illustrates the insect’s agility and strength.

Unlike humans, birds, and other vertebrate animals that contain an internal skeleton, insects have an exoskeleton that is finely textured with embedded color pigments and internal ridges for muscle attachments. Rather than lungs, insects have tiny holes (spiracles) in their sides and tubes (trachea) through which oxygen passively diffuses. For its size, the insect exoskeleton is incredibly strong, yet lightweight. However, insects could never grow to the size of this sculpture. They would suffocate for lack of oxygen and probably collapse under the weight of their own exoskeletons, which would have to be much thicker and heavier to maintain their shape.

Display drawer of insect specimens

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.044

Mimicry

Some insects are difficult to see because they blend in with their environment, while others seem to advertise themselves with bright colors. Insects with bright, high-contrast colors—black and orange or black and yellow—are often noxious and do not taste good, or may bite, or sting. They evolved these aposematic or repellant color patterns as a result of predators more easily recognizing the brightly colored individuals in the population. In some places, several different kinds of noxious insects have evolved similar aposematic color patterns. Referred to as Müllerian mimicry, this allows predators to learn to quickly identify these patterns.

Some insects that are palatable have evolved color patterns similar to the noxious species. Called Batesian mimicry, these imposters trick visual predators into thinking they will taste bad. Visual predators are not born knowing that aposematically colored insects taste bad; it is something they learn from experience. If there were more mimics (palatable insects) than models (noxious insects), predators would have a hard time learning this lesson. For Batesian mimicry to work, there needs to be more models than mimics in the area.

Viceroy butterflies mimic monarch butterflies who consume toxic milkweed plants as caterpillars, rendering them unpalatable. Entomologists originally thought viceroys exhibited Batesian mimicry. They recently discovered viceroys are actually unpalatable to birds and indeed demonstrate Müllerian mimicry.

Display drawer of Hemiptera specimens

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.052

True Bugs

When you say “bug” to entomologists, they assume you mean a true bug—an insect in the order Hemiptera. This group includes stink bugs, kissing bugs, water striders, cicadas, aphids, and many more. They all have stiff, beak-like mouthparts, like a hypodermic needle, that can pierce through plant tissue or other insects’ exoskeletons. By injecting saliva with digestive enzymes into their food, they are able to suck the fluids out with their straw-like mouthparts.

One group, cicadas, live underground as nymphs (immature stages) and emerge during the warm days of summer, filling the air with their buzzing. Some produce sounds of over one hundred decibels. Most cicadas have a one-year life cycle, with adults emerging each summer. But some species live underground for seven, eleven, or seventeen years (all prime numbers!) before emerging for only a few weeks as adults—all at the same time. Many cultures have captured cicadas in works of art, particularly in China where they symbolize rebirth and immortality.

Some bugs, such as lygus bugs and brown marmorated stink bugs, are serious agricultural pests, attacking fruits, vegetables, and other crops. Others, like big-eyed bugs, are important predators of these pests. Many true bugs are aquatic as both nymphs and adults.

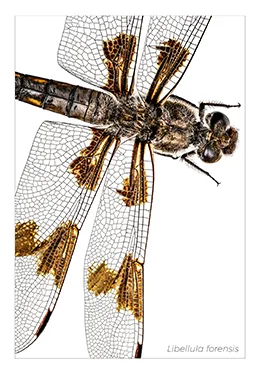

Display drawer of dragonflies (Anisoptera) and damselflies (Zygoptera)

Collection of the Essig Museum of Entomology, University of California, Berkeley

L2019.0401.017

Dragonflies and Damselflies

Dragonflies, and their more slender cousins, the damselflies, were among the first insects to evolve wings around 325 million years ago—long before dinosaurs roamed the earth. Shaped much like a helicopter, they use direct flight muscles—attached directly to the wings—to pull the wings up and down. However, because of how these muscles are attached, the wings cannot fold flat over their backs. Most other insects have indirect flight muscles, which change the shape of the thorax to which the wings are attached, causing the wings to flap up and down. This means they can fold their wings flat over their backs, making it easier to crawl around on plants, wood, and soil.

Adult dragonflies are aerial acrobats with large round eyes, able to hover or fly in any direction and even mate on-the-wing. They can fly at speeds up to thirty-five miles per hour. Their legs are lined with spikes, allowing them to capture and eat their prey while flying. Young dragonflies and damselflies, called nymphs or naiads, are aquatic predators, living in ponds, lakes, streams, and rivers. Many myths and cultural symbols derive from dragonflies, such as the devil’s darning needles sewing up the lips of little boys who lie.