Terminal 3

Woman petting a gazelle c. 1930s

Pierre Le Faguays (probably 1892–1962)/ pseudonym: Fayral

France

bronze

Courtesy of A. C. Griffing and Barrett Lindsay-Steiner

L2014.1402.002

One of the most prolific and influential Art Deco sculptors of the interwar period, French artist Pierre Le Faguays created a vast range of works in mediums such as bronze, marble, and ceramics.

Sculpture

Decorative sculpture was highly desired throughout the interwar years of the 1920s and ’30s. The majority of these sculptures were made in European countries such as France and Austria, which had established metal foundries. Commonly crafted from bronze and marble and widely exported, models were made in many scales and levels of manufacture to appeal to a variety of budgets. Art Deco artists delighted in depicting the contemporary female form. Sleek and slender women with cropped hairstyles were depicted in the nude, as mythical figures, doting over animals, in seductive poses, or dressed in fashionable costumes inspired by Parisian stage and fashion magazines.

Vase c. late 1920s–30s

Boch Frères Keramis

Belgium

ceramic, glaze

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.017

Gazelle vase c. late 1920s–30s

Charles Catteau (1880–1966)

Boch Frères Keramis

Belgium

Courtesy of A. C. Griffing and Barrett Lindsay-Steiner

L2014.1402.003

Ceramics

During the 1920s and ’30s, artisans reinterpreted classic pottery shapes and decoration in the Art Deco style. Ceramics took on a fresh, modern appearance. As in other mediums, France led the way in Art Deco-inspired ceramics, but many other European countries also produced wares. The Belgian firm Boch Frères Keramis made large quantities of distinctive ceramics with slip-cast bodies and eye-catching, hand-painted decoration. The wares were sold internationally in scores of fashionable galleries and department stores. The firm employed many French-trained artists, most notably Franco-Belgian Charles Catteau. In 1907, at age twenty-seven, he became the head of the decoration department at Boch Frères Keramis. Catteau obtained international recognition at the Paris Exposition of 1925 (Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs Industriels et Modernes).

Phonograph c. 1920s

Parlophon

Germany

metal, wood, paint

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.082

Before the introduction of the radio, the phonograph appeared in many American homes. Phonograph records helped spread new musical genres, such as jazz, blues, and country music to locations where live music venues did not exist.

Vase c. late 1920s–30s

Charles Catteau (1880–1966)

Belgium

glass

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.008

Vase c. late 1920s–30s

France

glass

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.007

Glass Vases

A demand for new styles of glass grew after World War I, in particular, lighting fixtures, perfume bottles, tableware, and ornamental items such as vases. Glass transformed interiors by providing an alternative to more traditional materials. New techniques were developed to create high quality glass well suited to the sculptural forms popular at the time. Glass was blown, molded, cast, cut, carved, sandblasted, mirrored, engraved, and enameled. New coloring and acid-etching techniques were employed to create entirely original effects. Decorative glass became available to suit a variety of tastes and budgets.

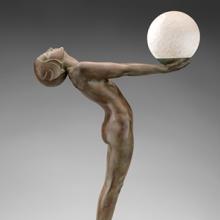

Clarté light statue 1928

Max Le Verrier (1891–1973)

France

bronze

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.026

Max Le Verrier

After serving in the French army during World War I, French sculptor Max Le Verrier studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva before returning to France in 1919 where he established a studio in Paris. Le Verrier was awarded a gold medal for his sculptures at the 1925 Paris Exposition (Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs Industriels et Modernes). In 1926, Le Verrier opened his own foundry, casting pieces for a wide range of French sculptors of the period, including Pierre Le Faguays. He also continued to sculpt his own creations. In the 1920s, he focused on the idealized female form, a popular Art Deco subject matter. He used live models to create his famous Clarté statue in 1928. It was offered in four sizes, the largest of which is on view at the Hôtel Lutetia lobby in Paris. Le Verrier worked throughout the 1930s, until World War II halted his work. After the war, he continued to sculpt until his death in 1973.

Airplane cocktail shaker c. 1930s

Germany

chrome-plated metal

Courtesy of A. C. Griffing and Barrett Lindsay-Steiner

L2014.1402.004

Cocktail shakers inspired leading designers. They were made from glass, silver, silver-plated or chrome-plated metal, and also from glass. The classic cocktail shaker took the form of a tall, graduated cylinder, but more novel forms, such as airplanes and penguins, were also popular

Cocktails

Cocktail parties became an established institution in the 1930s after Prohibition ended. They usually began in the late afternoon or early evening. ‘Cocktail is King’ reads a chapter header in Burke’s Complete Cocktail and Tastybite Recipes (1936), where the author proclaims, “there is no denying that the cocktail’s heyday is here; for the next few years every hour will be the Cocktail Hour, so to speak. Therefore we must make our bow and render service to the cocktail.” Cookbooks, newspapers, and magazines such as Burke’s offered advice on how to conduct cocktail parties, including how to mix drinks, which appetizers to serve, and how to entertain guests. To accompany highballs, Susan Mills, in a 1934 Washington Post article, recommended dainty sandwiches—“thin slices of buttered bread, with a layer of chopped watercress seasoned with a little lemon juice or mayonnaise.” She also encouraged hosts to “try to appear as if entertaining was the easiest thing in the world.”

Assorted compacts and eye shadows c. 1920s–30s

United States, Europe, and Argentina

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.190.02-.04, .265, .265.02, .265.03, .265.04, 267

Women’s Beauty Products

The signature look of the 1920s combined rich red lips, pale powdered skin, and dark, smoldering eyes. Early Hollywood actresses helped popularize cosmetics. Women emulated the looks of their favorite stars such as Clara Bow’s cupid bow lips. Prior to this period, bold makeup was discouraged; only stage actresses wore such daring looks. By the 1920s, cosmetics counters proliferated in drug and department stores. Uninhibited ladies could now freely experiment with the latest powders and lipsticks. Innovations that aided in the ease of makeup application also occurred around this time. Compact cases containing rouge or blush and the swivel lipstick tube became available. Retailers also offered brightly colored nail polish by the end of the 1920s. Moon manicures, in which women painted only the middle of their long nails, while leaving the crescent tips untouched, were fashionable throughout the 1920s and ’30s. Mascara, still in its infancy, commonly came in a cake form that was combined with water and applied with a flat bristle brush.

Clock c. 1930s

England

glass, chrome-plated metal

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.076

Clocks

The ubiquitous clock experienced radical design changes during the Art Deco era. Electric desktop and wall clocks that required no winding now decorated interiors. Other clocks only required weekly rather than daily winding. Clocks appeared in multiple rooms throughout the home, and alarm clocks filled store shelves. Sleek, angular clocks appeared minimal and austere compared to the round shapes of previous decades. Straight lines took the place of arrow-shaped arms. Sharp angular lines or chrome-plated balls replaced numerals. Traditional, richly grained wooden clocks encased in cherry or mahogany were replaced with chrome-plated metal. Other clocks were made in luxurious materials, such as marble and bronze. Manufacturers offered clocks for the budget-minded made from newly developed Bakelite, an early plastic. The French clockmaker JAZ became known for their Bakelite clocks in the 1930s, which they referred to as Jazolite.

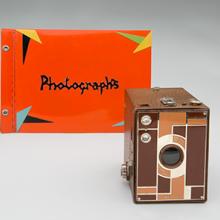

Photo album c. 1930s

United States

Bakelite

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.288

Brownie camera c. 1930s

Eastman Kodak Co.

Rochester, New York

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.074

In 1900, Kodak introduced the Brownie, the first hand-held portable point-and-shoot camera for the general public. By the 1920s and ’30s, bringing a camera along on vacation was customary for a growing number of travelers.

Travel

The Art Deco age marked the beginning of mass travel. In the 1920s, ocean liners and trains served as the dominant means of transportation, providing comfortable, reliable transport to millions of vacationers. Ocean liners were symbols of modern technology, wealth, and national pride. At the same time, streamlined trains evoked speed and modernity, with private companies and state railways competing to build even faster and more luxurious models. Commercial air travel, though still in its infancy, captured America’s imagination during the 1920s. Airplanes were primarily used for mail delivery, but toward the end of the decade, planes were increasingly used for passenger transport. By 1921, in addition to mass transportation, the number of automobiles in the United States passed the ten million mark. The construction of the United States’ first transcontinental highway from New York to California was completed in the 1930s.

Radio c. 1930s

Northern Electric

Montreal

Bakelite

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.085

Radios

Of all the new appliances to enter American homes during the 1920s, the radio had a revolutionary effect. For the first time in the nation’s history, people across the country could simultaneously hear the same program or music. Radio drew the nation together by bringing news, entertainment, and advertisements to millions of households by 1929. By the 1930s, when radio popularity reached its zenith, Bakelite plastic radios commonly appeared in homes. Radio designers created sleek models in streamlined Art Deco styles.

Tabletop jukebox c. late 1930s

Wurlitzer

Cincinnati, Ohio

wood, metal, paint

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.095

The Jukebox

Before the introduction of the radio, the phonograph was found in many American homes. Radio programming and the stock market crash of 1929 nearly put an end to phonograph record sales. The repeal of Prohibition in 1933, however, revived the medium. Approximately 150,000 coin-operated automatic phonograph machines were produced between 1933 and 1937. Soon to be labeled jukeboxes, each automated machine held fifty records. New, commercial, record-playing jukeboxes now appeared in bars, restaurants, dance halls, nightclubs, and soda fountains in cities and towns across the country, providing low-cost entertainment.

The jukebox made dancing more prevalent than ever before with young Americans. New dances were regularly introduced. Swing dance was wildly popular in the second half of the 1930s among high school and college students. The exuberant style blended jazz with big-band orchestration and danceable rhythms.

Decanter and glasses c. 1930s

Czechoslovakia

glass

Courtesy of Art Deco Collection

L2014.1401.057.01-.07

Glass

Artisans produced a variety of innovative glass creations during the interwar years, particularly in French and Bohemian or Czech factories. Although France and Bohemia dominated glass production in Europe, Art Deco glass was also produced on a smaller scale throughout continental Europe, Scandinavia, and Great Britain. In the United States, Steuben Glass Works became the most respected American artistic glass manufacturer during the 1920s. The decanter set shown here showcases bold, black geometric lines, an Art Deco design element that became particularly fashionable in the 1930s.