International Terminal

LCW chair c. 1944–45

Designed by Charles (1907–78) and Ray (1912–88) Eames

Evans Products, Molded Plywood Division

Venice, California

ash plywood, plastic resin, melamine, rubber

Collection of Steve Cabella

L2016.1501.018

Eames LCW [Lounge Chair, Wood]

Eames plywood chairs exhibit a functional and sculptural, harmoniously simple design that flexes to fit the sitter through pivoting rubber shock-mount connections. Developed from 1943–48 by Evans Products’ Molded Plywood Division, the project was based initially on a conventional, single-piece seat and back. A two-piece design proved more practical and cost effective, with separate seats and backs formed from sheets of wooden veneer that were glued and pressed between heated steel and plaster molds. Molded plywood chairs were available in ash, birch, rosewood, and walnut veneers in natural, red, or black finishes, or upholstered in a variety of animal hides, fabric, leather, or Naugahyde vinyl.

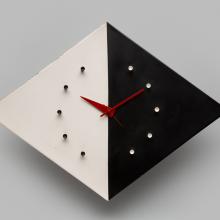

Model 2201 Kite wall clock 1950

Designed by George Nelson (1908–86)

Howard Miller Co.

Zeeland, Michigan

aluminum, golf tees, metal, paint

Collection of Steve Cabella

L2016.1501.034

George Nelson

Trained in architecture at Yale University and in Rome, George Nelson (1908–86) melded European modernism with American industrial design in furniture, household items, and modular office components. As Herman Miller’s Design Director, he created the “Slat Bench,” “Case Series,” and “Coconut Chair,” authored catalogs, directed brand identity, and hired new designers including Alexander Girard, Isamu Noguchi, and Charles Eames. Nelson’s clocks for the Howard Miller Company incorporated standard movements into artistic and whimsical housings of industrial materials such as wood, aluminum, brass, and plastic.

Radio Nurse baby monitor 1937

Designed by Isamu Noguchi (1904–88)

Zenith Radio Corp.

Chicago

Bakelite, plastic, metal

Collection of Steve Cabella

L2016.1501.004.01

Bakelite

Industrial designers refined and streamlined an array of domestic items during the mid-twentieth-century. From cameras and radios, to vacuum cleaners, record players, and automobiles, they designed and restyled products that were modern in both appearance and function. Innovative materials were central to modern design and the streamlined look. In 1907, Belgian chemist Leo Baekeland (1863–1944) invented the first synthetic plastic. Patented as Bakelite, it was lightweight, easily molded, and an excellent electric insulator. Sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–88) designed the “Radio Nurse” speaker for Zenith, the world’s first baby monitor, with this new Bakelite plastic.

Cobra table lamp 1950

Designed by Greta Magnusson-Grossman (1906–99)

Ralph O. Smith Co.

Burbank, California

aluminum, enamel, steel, chrome, plastic

Collection of Steve Cabella

L2016.1501.039

Lamps and Good Design

Good design was modern and organic, based on simple structures, clean lines, and honest materials. The “Cobra” lamp by Greta Magnusson-Grossman (1906–99), with its asymmetrical shade and curved base connected by flexible arm, was selected for the 1950 “Good Design” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Educated at the Konstfack College of Design in Stockholm, Magnusson-Grossman worked in architecture, interior and industrial design, and was one of the first to introduce modern Scandinavian design to the California marketplace with her move to Los Angeles in 1940.

Tea set: teapot, sugar, creamer, tray 1950

Peter Macchiarini (1909–2001)

San Francisco

silver, teak

Courtesy of The Modern i Shop

L2016.1501.065.01–.04

Peter Macchiarini

Born in Northern California and raised in Italy, jeweler and sculptor Peter Macchiarini (1909–2001) trained at the Art Academy in Pietrasanta in marble carving and ornamental art. A decade after he returned to the West Coast, Macchiarini switched gears and in 1938 began a career in the metal arts, self-taught through books on jewelry making and Bauhaus design. Macchiarini was an active community organizer and co-founder of the Metal Arts Guild and San Francisco Art Festivals, and his studio in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood was a hub of creativity and discussion for mid-century artists.

Basket 1950

Ruth Asawa (1926–2013)

San Francisco

copper wire

Courtesy of The Modern i Shop

L2016.1501.063

Ruth Asawa

Ruth Asawa (1926–2013) worked in sculpture and created a handful of functional objects. While confined in a Japanese American internment camp during the Second World War, Asawa learned to draw from Tom Okamoto, a Disney animator also interned at the camp. After a trip to Mexico, she was inspired by looped wire basketry used to store produce and eggs in the marketplace. Asawa combined traditional Mexican wire looping with her line drawing designs and wove complex and flowing three-dimensional hanging mobiles, similar in construction to the egg basket pictured here.

Candelabra 1948

Adaline Kent (1900–57)

San Francisco

magnesite, brass

Collection of Steve Cabella

L2016.1501.059

Adaline Kent

Decorative arts take many shapes, from lighting and furniture, to serving utensils, storage vessels, and other artistically rendered housewares. Influenced by modern art and design, mid-century decorative arts were created in large numbers by manufacturers, and as unique pieces by craft and fine artists. Adaline Kent (1900–57) worked primarily in fine arts sculpture and crossed into the decorative arts with this sculpted candelabra. Kent was one of San Francisco’s leading surrealistic sculptors during the 1950s, known for her abstract and biomorphic carvings in stone, magnesite, and concrete.

Special Model K portable electric phonograph 1940

Designed by John Vassos (1898–1985)

RCA Victor

New York

aluminum, steel, plastic, felt

Collection of Steve Cabella

L2016.1501.005

Industrial Design

By the 1930s, American industrial designers were balancing form and function with technological innovation and new materials. There was no dedicated training at first for industrial designers, and most professionals began as artists, architects, and illustrators. John Vassos (1898–1985) started as an advertising designer for Packard Motor Cars, and then worked for RCA, where he introduced the round tuning dial and push-button selector to radio design. For American modernism to be commercially successful, Vassos felt it could not be radical, and he carefully executed designs that softened the harder edges of European modernism with streamlining and sweeping lines.

3-Quart Coffeemaker, Pint Coffeemaker and Flash Waterbath 1949 | Gas Kettle 1950 |

Chemex

Dr. Peter J. Schlumbohm (1896–1962) utilized scientific laboratory materials to produce some of the simplest and most inventive mid-century designs. Inspired by a chemist’s funnel and beaker, his Chemex “Coffeemaker” combines a single piece of hourglass-shaped Pyrex® glass, a conical filter of laboratory-grade paper, and a wooden collar fastened with a rawhide tie. A companion to the coffeemaker, the “Gas Kettle” features an ingenious glass-and-cork shuttle valve to control escaping steam. Dr. Schlumbohm held over 300 patents and created an array of inventions, with more than twenty examples in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection in New York.

Cinderella garbage pail 1940

Designed by Dr. Peter J. Schlumbohm (1896–1962)

Chemex Corp.

New York

aluminum, cork, birch

Collection of Steve Cabella

L2016.1501.010

Aluminum

Aluminum made twentieth-century modern marvels such as airline travel, refrigeration, and space flight a reality. Early uses of aluminum included power transmission lines, overhead electrical wiring for streetcars, and internal combustion engines such as the Wright brothers’ four-cylinder 1903 Flyer engine. Industrial designers promoted aluminum’s strength, light weight, conductivity, and luster in an astounding array of products, from metallic paint and textiles, to TV dinner trays, washing machines, food packaging, and Greyhound busses. Modern designers employed aluminum extensively in mid-century architecture, while sleek, space-age aluminum items reflected progress through technology in products for the home.

Brooch 1950 | Brooch 1950 |

Modern Jewelry

One of the first American modernist jewelers, Margaret De Patta (1903–64) referred to her jewelry as “wearable sculpture.” She studied at the School of Design in Chicago under Bauhaus artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), who encouraged her to “catch your stones in the air. Make them float in space. Don’t enclose them.” In a departure from traditional jewelry that focused on precious gemstones, De Patta’s work balanced the entire composition, with quartz, pearls, or beach pebbles added as accents in flowing harmony. Another local jeweler, Peter Macchiarini (1909–2001) championed handcrafted art and the role of craft artisans. Macchiarini’s jewelry often combined brass, ebony, silver, and other materials to accentuate contrast.

Space Spider 1955

Designed by Robert Walker

Walker Products

Berkeley, California

Package designed by Walter Landor (1913–95)

Walter Landor and Associates

San Francisco

cardboard, paper, ink, fluorescent thread

Collection of Steve Cabella

L2016.1501.029

Toys and Games

To inspire young artists and spark children’s creativity, many mid-century toys and games promoted good design. “Space Spider,” a design game by Walker Products of Berkeley, consisted of perforated shapes and spools of fluorescent thread to make a variety of space age, glow-in-the-dark patterns. The game incorporated package design by Walter Landor (1913–95), a leader in modern packaging whose San Francisco-based design firm pioneered a multi-disciplinary approach that included consumer psychology and market research.