International Terminal

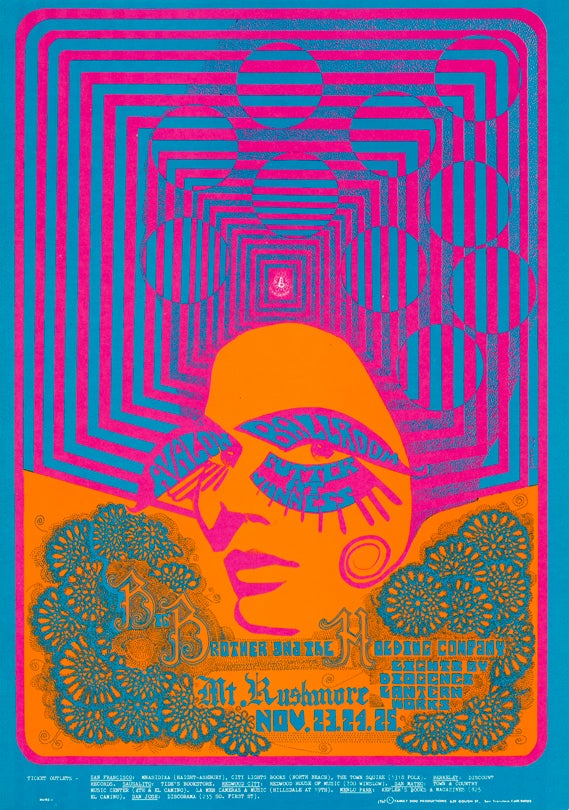

Big Brother and the Holding Company November 23–25, 1967

Artist: Joe Gomez

Avalon Ballroom

San Francisco

From the collection of Marilyn and Michael W. Lucas

FD-93

L2014.2407.029

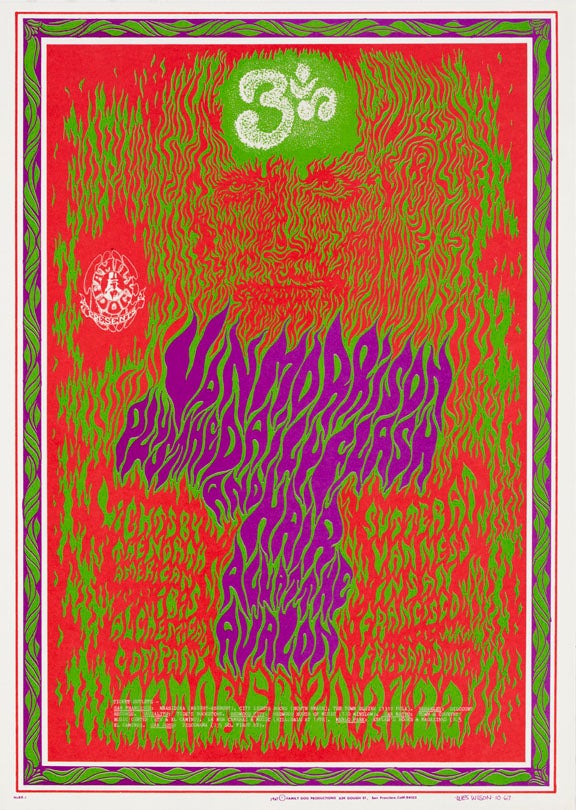

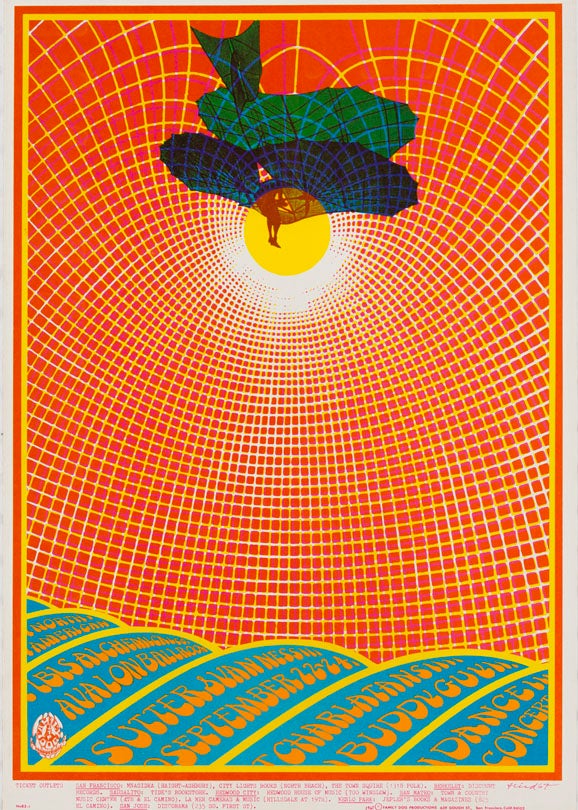

Van Morrison October 20–22, 1967

Artist: Wes Wilson

Avalon Ballroom

San Francisco

Courtesy of Ron Schaeffer

FD-88

L2014.2411.010

Wes Wilson—Defining the Genre

Wes Wilson is often described as the father of the rock poster, even though in June of 1965, George Hunter and Michael Ferguson of The Charlatans designed “The Seed,” which is widely considered the first true rock poster of the 1960s. Later that fall, Ami Magill and Alton Kelley created many of the earliest Family Dog posters and handbills for a number of dance concerts at Longshoremen’s Hall.

But if Wilson was not the first artist to produce a rock poster, he was very close. He started designing handbills for the Family Dog in mid-January of 1966. His access to a printing press made it possible for him to design, print, and deliver a poster for as little as $60.00, which fit the Family Dog’s paltry budget perfectly.

However, Wes Wilson was the first to develop a poster style suggesting what might await anyone willing to pay $2.50 to attend a show at the Fillmore Auditorium or Avalon Ballroom. Wilson’s lettering was restless, rarely willing to do its job in neat, orderly rows. With the exception of his first poster for Bill Graham, almost all the rest are festivals of color, pulling liberally from the twelve basic hues (Wilson had a special fondness for orange and red). Through his posters, Wilson gave would-be concertgoers a sneak peek at the light-show-streaked music scene inside San Francisco’s two most storied venues. More importantly, his work helped define an entire genre of graphic art.

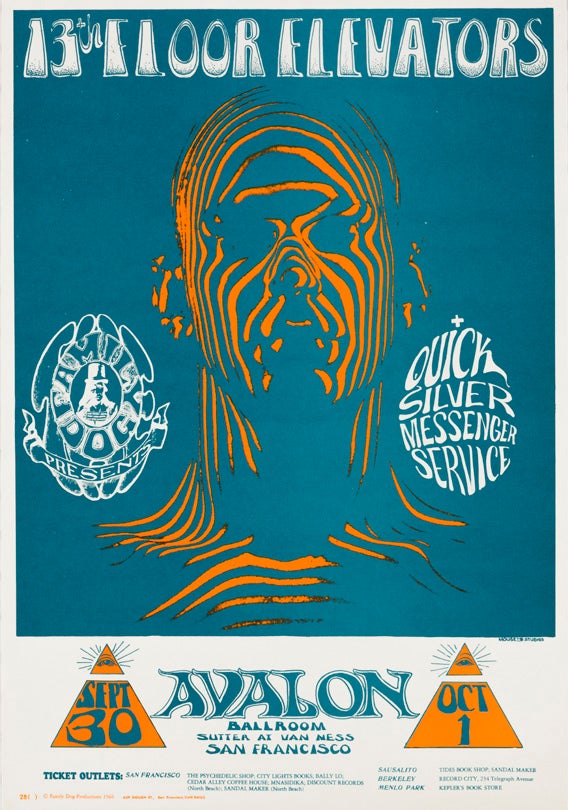

13th Floor Elevators (Zebra Man) September 30–October 1, 1966

Artists: Alton Kelley, Stanley Mouse

Avalon Ballroom

San Francisco

From the collection of Marilyn and Michael W. Lucas

FD-28

L2014.2407.005

LIFE magazine December 6, 1954

Photographer: Ralph Morse

Courtesy of Ben Marks

L2014.2414.051

Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse—Psych Goes Pop

As the most artistically inclined member of the Family Dog, a group of like-minded free spirits who lived communally in an old Victorian in San Francisco, Alton Kelley was naturally called upon to design posters and handbills for some of the earliest Family Dog shows of 1965. He met hot-rod artist Stanley Mouse—whose first evening in San Francisco was spent at the Trips Festival—in 1966. Soon afterwards, the two were working as partners, first on posters for Family Dog shows at the Avalon Ballroom and then on projects for the Grateful Dead, the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, and a smattering of concerts at the Fillmore for Bill Graham.

In rough terms, Kelley was responsible for images and layout while Mouse did the lettering and borders. Beyond this loose division of labor, what made their collaborations notable was their use of appropriated images from the past, whether taken from advertising, movie stills, or the covers of magazines. Their work was not Pop in the sense of Andy Warhol, but it did push the edges of what it meant to create a work of art. In their case, a work of graphic art designed to sell concert tickets in the 1960s. Indeed, their first collaboration for a Big Brother and the Holding Company/Quicksilver Messenger Service concert at the Avalon, which lifted the logo from Zig-Zag brand rolling papers, included this shades-of-things-to-come message from the artists: “What you don’t know about copying and duplicating won’t hurt you.”

The Zebra Man poster is one of the most psychedelic in rock music, but its source is grounded in military technology of the 1950s. The main image is taken from a photograph by Ralph Morse, whose December 6, 1954 cover story for LIFE called “Jet Age Man” explored how high-tech was being used to train and equip the men who flew B-47 Stratojet bombers. In Morse’s cover photograph, a pilot is having the contours of his face mapped so he can be fitted for a flight helmet. Kelley and Mouse were not the only rock poster artists who thought Morse’s pilot had psychedelic appeal. Gary Grimshaw used the same image three weeks later on a poster for an MC5 show at Detroit’s Grande Ballroom.

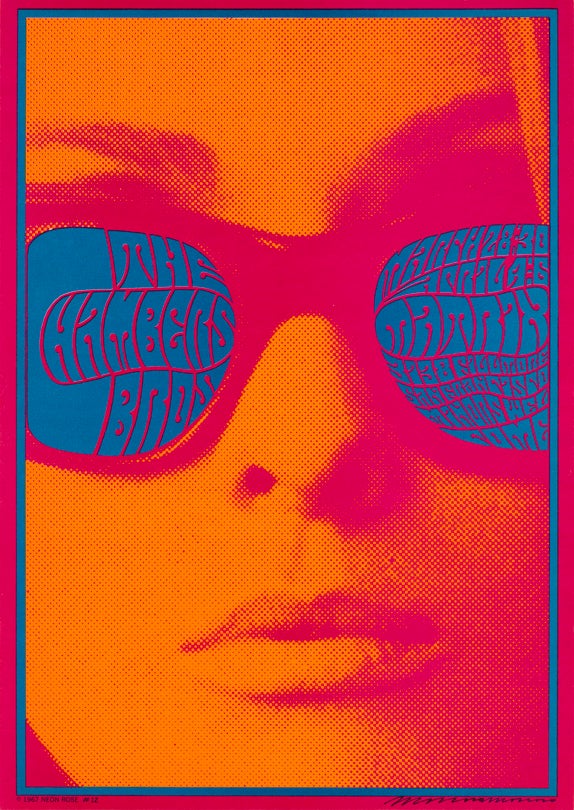

The Chamber Brothers March 28–30, April 4–6, 1967

Artist: Victor Moscoso

Matrix

San Francisco

Courtesy of Vance Carpenter

NR-12

L2014.2405.006

Victor Moscoso—Color Fetish

Looking at Victor Moscoso’s posters, “discipline” is probably not the first word that comes to mind. His color-drenched compositions are dominated by illuminant hues designed to confuse the eye, while his lettering is often deliberately illegible. But Moscoso came by his psychedelic sensibility the hard way, learning his craft under the rigorous tutelage of Yale professor Josef Albers, whose legendary obsession with color made a deep impression on the Spanish-born artist. And unlike the other poster artists, Moscoso later taught at the San Francisco Art Institute.

It was his training as an artist rather than the nature of his employment that really set him apart from his contemporaries. Wilson’s aesthetic was maturing at the speed of light due to the blizzard of deadlines he was under, while Griffin was remaking surf art for the counterculture, one flying eyeball at a time. For their part, Kelley and Mouse were treating poster design almost like graphic improvisation. In contrast, Moscoso was able to quickly recognize what was working, and then lock it in, resulting in a body of work that is perhaps the most stylistically cohesive of any poster artist of the era. That is why a Neon Rose poster is instantly recognizable for the way its colors positively hum, and why the half-dozen or so framed-collages he did for the Family Dog feel like a mini-series all their own.

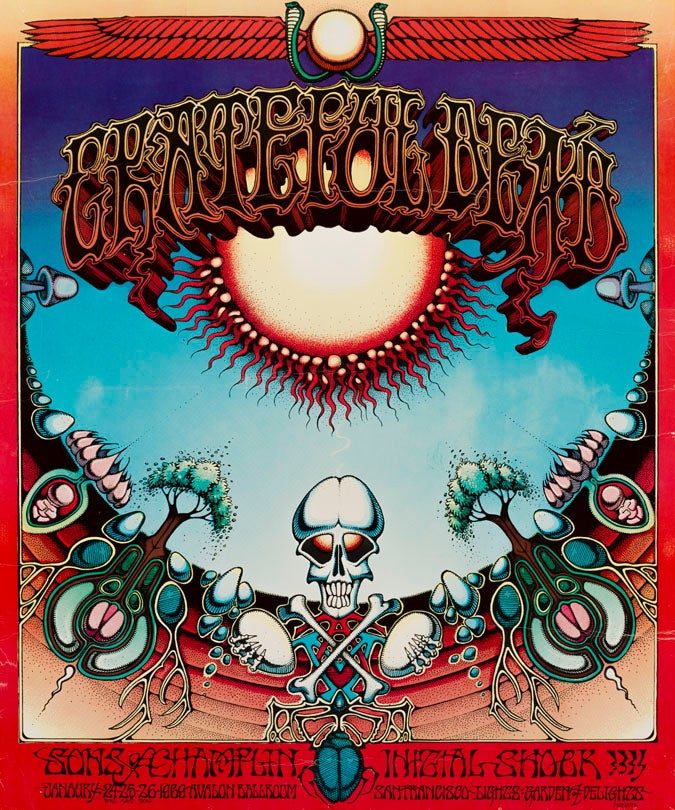

Grateful Dead January 24–26, 1969

Artist: Rick Griffin

Avalon Ballroom

San Francisco

Courtesy of Mark Rodriguez

AOR-2.24

L2014.2410.002

Rick Griffin—The Genius of Pen and Ink

When Rick Griffin settled in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1966, he brought more than the sunny surf-graphics of Southern California with him. He also arrived with influences gleaned from childhood road trips with his amateur archeologist dad, with whom he explored Native American sites and ghost towns in the Southwest; an affinity for advertising art; and his then-unrealized visions of disembodied organisms and mythical creatures. For instance, Griffin’s most famous phantom entails a winged eyeball peering through a circle of fire, a human skull clamped tight in its reptilian claws.

In short, Griffin could get very weird—as a draftsman he was equally unparalleled. But Griffin was not just a talented lone wolf, cranking out images in solitude for the Family Dog, Bill Graham, and a poster publisher in the East Bay called Berkeley Bonaparte. He was a serial collaborator, too, contributing his pen to posters co-designed by Alton Kelley and Stanley. His collaborations with Victor Moscoso were especially fruitful, particularly their pair of posters for two sets of shows on consecutive weekends, headlined by Jimi Hendrix and Iron Butterfly, respectively. With lettering and central images by Griffin, plus radiating backgrounds, and dancing yin-yang symbols by Moscoso, these classic rock posters represented not just a meeting of two intensely creative minds, but a melding

Beilenson Bein May 16, 1967

Artist: Unknown

California Hall

San Francisco

Courtesy of Marty Hohn

L2014.2406.009

Beyond the Fillmore and Avalon

The dance halls managed by Bill Graham (the Fillmore Auditorium, Winterland, Fillmore West) and Chet Helms (the Avalon Ballroom, Family Dog on the Great Highway) get most of the attention when the conversation turns to the San Francisco music scene of the late 1960s. But these venues were by no means the only ones, or even the city’s first. In 1965, dance concerts were held at California Hall, Longshoremen’s Hall, and at a small club in the Marina district called the Matrix.

In 1966, the scene exploded, with shows running simultaneously at the Matrix, the Fillmore (for a brief period, shows were produced there by both Chet Helms and Bill Graham, until Graham, who held the lease, ousted his competitor), the Avalon, and California and Longshoremen’s Halls. In February, the first dance concerts were held at the Firehouse. In August, East Bay promoter Bill Quarry produced a show featuring the Yardbirds at the Carousel Ballroom, which was managed for a few months in 1968 by the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane before becoming the home of the Fillmore West.

Sokol Hall was also the site of a couple of shows in 1966, including a benefit for the Hells Angels. By the fall of that year, Western Front had opened, commissioning posters from Greg Irons and Stanley Mouse. The Rock Garden enjoyed a brief run in 1967, and California Hall artist Michael Wood/Pyxis Studios created diamond-shaped posters for some of the shows there. Meanwhile in the Haight-Ashbury, the Haight Theater was renamed the Straight. When the struggling operation was denied the dance permit needed to host a concert, the Straight rebranded its shows as dance classes.

Charlatans September 22–24, 1967

Artist: Robert Fried

Avalon Ballroom

San Francisco

Courtesy of Ron Schaeffer

FD-83

L2014.2411.054

A Profusion of Talented Artists

Although the history of San Francisco rock posters is often told through the work of the so-called Big Five (Wilson, Kelley, Mouse, Moscoso, and Griffin), scores of artists contributed to the graphic-arts phenomenon. Some of these artists produced numerous posters for shows at the Avalon, the Fillmore, and other venues in 1967 and 1968. Others only did only a few.

Of the artists who were given the opportunity to showcase a significant body of work, Robert Fried is one of the most noteworthy. Fried designed posters for the Family Dog, poster publisher Berkeley Bonaparte, and Bill Graham, often taking the color tricks of Moscoso to even “trippier” optical heights.

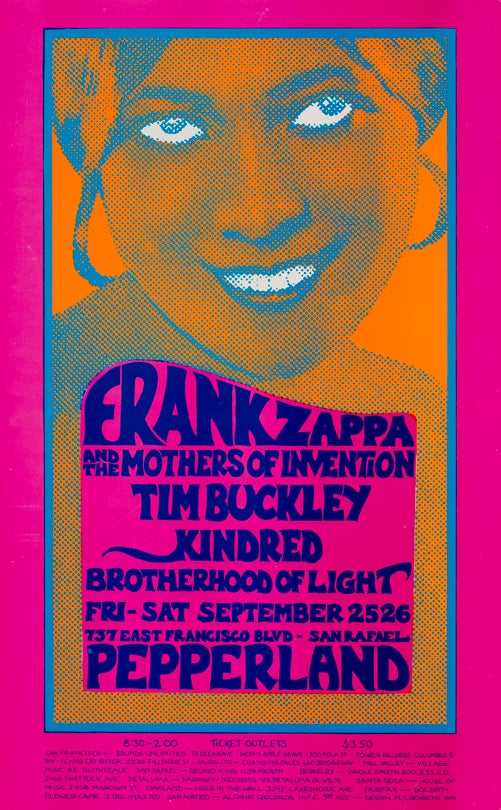

Frank Zappa September 25–26, 1970

Artist: Mark Twain Behrens

Pepperland

San Rafael

Anonymous lender

AOR-4.86

L2014.2413.002

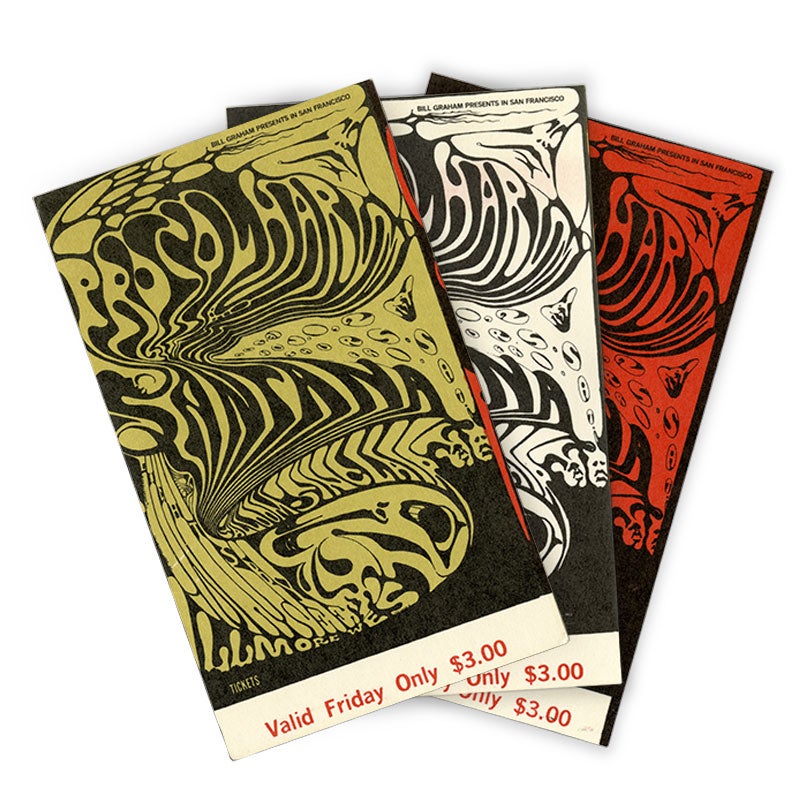

Procol Harum tickets October 31–November 2, 1968

Artist: Lee Conklin

Fillmore West

San Francisco

Courtesy of Ron Schaeffer

L2014.2411..074.01-.03

Lee Conklin—Psychedelic Body Language

Bonnie MacLean’s year-and-a-half-long run as the Fillmore’s resident poster artist effectively ended with her 1967/1968 New Year’s Eve poster. The following weekend, Lee Conklin joined the Bill Graham stable and began a year-and-a-half-long run of his own with a poster for three Vanilla Fudge/Steve Miller Band shows at the Fillmore and Winterland. Coincidentally, Conklin would eventually design essentially the same number of posters as MacLean. But while MacLean’s work had differed incrementally, though importantly, from Wilson’s before her, Conklin’s approach was a radical departure. His was a world filled with human figures, animals, and body parts, which often appeared to melt together. Whereas MacLean brought a painter’s eye to her work, Conklin was the consummate illustrator.

In another coincidence, one of Conklin’s earliest posters for Graham was distributed the same month as Griffin’s famous “Flying Eyeball” for Jimi Hendrix’s four-night run at Winterland. Headlined by The Who, with support by the great jazz alto-saxophonist Cannonball Adderley (misspelled on the poster), the image featured a number of flying figures whose bodies were mostly humanoid and whose wings were composed of pairs of ears. Now a favorite of many contemporary rock-poster artists, the composition addressed the real reason most people went to concerts in the first place—to hear the music. Another Conklin reference to the experience inside the concert hall was his design in October of 1968 for a Canned Heat show at the Fillmore West. The swirling watercolor-like composition echoed a psychedelic, liquid light show.

When tickets were needed for shows advertised by two-color posters such as the one for Procol Harum, the printer would sometimes change the poster’s second color on the ticket so that they were easily distinguishable by busy ticket takers.

Jim Kweskin Jug Band October 7–8, 1966

Artists: Alton Kelley, Stanley Mouse

Avalon Ballroom

San Francisco

From the collection of Marilyn and Michael W. Lucas

FD-29

L2014.2407.004

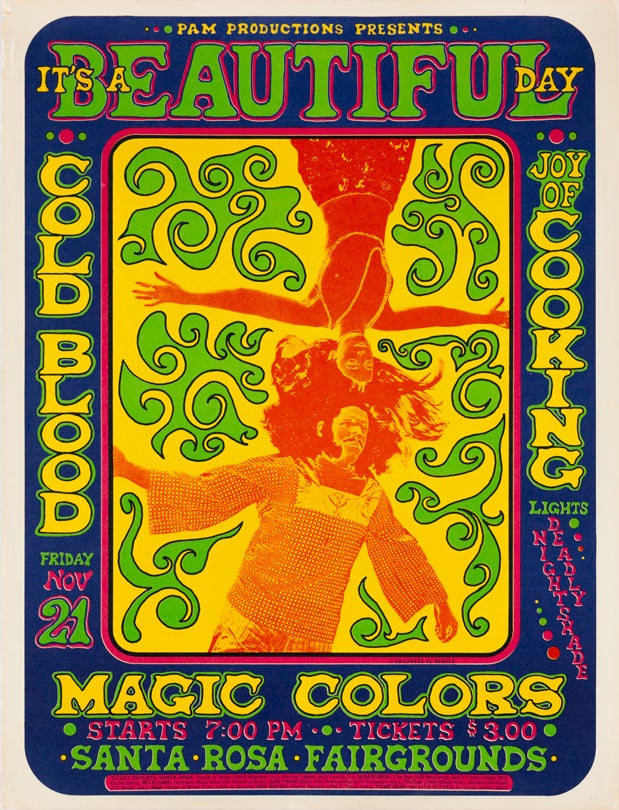

It’s a Beautiful Day November 21, 1969

Artist: Larry Noggle

Santa Rosa Fairgrounds

Santa Rosa

Courtesy of Ron Schaeffer

AOR-2.333

L2014.2411.053

Sights and Sounds, North and South

Beginning in 1967, as the Haight-Ashbury was becoming overrun with wannabe hippies, many of the bands whose music had lured them to San Francisco fled to Marin County on the other side of the Golden Gate Bridge. There, musicians played casual gigs at holes-in-the-wall like the Lion’s Share in San Anselmo. It was the sort of place where Van Morrison would show up unannounced to play a set of the blues, or where the Grateful Dead would perform for Janis Joplin’s wake in 1970. About a half hour north of the Lion’s Share, in the little town of Cotati, was the Inn of the Beginning, whose audience came from students at nearby Sonoma State. Bands like Bronze Hog, Lamb, and the Joy of Cooking were regulars at the Inn, as was former Charlatans singer Dan Hicks.

Marin’s most visible landmark, Mt. Tamalpais, was the site of larger concerts at its outdoor amphitheater. The most ambitious of these was the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival in June of 1967, at the height of the Summer of Love. Heavily promoted by AM radio station KFRC, the two-day benefit concert featured performances by The Doors, The Byrds, Jefferson Airplane and twenty or so other bands. A pair of posters was commissioned from Jack Hatfield, and the Hells Angels provided “security.” Their presence was far more benign than it would be two years later at the free Rolling Stones concert at Altamont. Some band members beat the traffic from the Sausalito heliport up to the venue by hopping onto the back of a Hells Angels’ motorcycle.

Sin Dance April 29–30, 1966

Artist: Wes Wilson

Avalon Ballroom

San Francisco

Courtesy of Ron Schaeffer

FD-06

L2014.2411.001