Terminal 2

Six-drawer chest c. 1840

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community

pine, fruitwood, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

CS2007.04.07

L2012.2701.046

A Place for Everything and Everything in its Place

The Shakers’ industrious, communal lifestyle required a need for order and efficiency. To fulfill these requirements, the Shakers fabricated chests of drawers or built-in drawers and cupboards in nearly all of their buildings. These extraordinarily efficient storage units were particularly helpful during the first half of the 1800s when Shaker communal societies had the largest number of family members. The amount of attention and time devoted to the creation of storage units is truly impressive. These large storage units were some of the most complex and exemplary forms of furniture produced by Shaker craftsmen. Hundreds of freestanding pieces were designed and built to accommodate the specific needs of various communities.

Entire walls often contained built-ins composed of drawers, shelves, cupboards, and closets. One such structure built in Enfield, New Hampshire, during the mid-1800s contained more than 860 built-in drawers. The Shakers fabricated cases of drawers that stretch from floor to ceiling and include twelve, twenty-four, or as many as forty-eight drawers in a single unit. Rather than appearing overwhelming, these floor-to-ceiling, built-in storage units form tranquil designs of horizontal and vertical lines.

Chair c. 1852

Canterbury, New Hampshire

made for the Community

birch, maple, stain, caning

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

CH2007.08.02

L2012.2701.056

Brother’s chair c. 185

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community

birch, maple, caning

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

CH2007.10.07

L2012.2701.055

Community Chairs

Shaker chair design stems from eighteenth-century New England vernacular furniture. The Shakers emulated the ladder-back or slat-back chair, a light, durable chair that could be easily constructed. The number of slats a chair had depended on the height of the back of the chair. Craftsmen typically made dining and work chairs with two slats, side chairs with three, and armchairs with three to five slats. Each Shaker community made unique styles of pommels or finials to adorn chair posts. Because craftsmen in each community developed a special way of shaping chair pommels, it is often possible to identify the community where a Shaker chair was made. Early seat upholstery consisted of splint, woven straw, cane, and leather. During the 1830s, colored wool tape, which was made on looms in Shaker communities, was commonly woven into different patterns to form chair seats. Chairs, like other furniture, were often recycled or refinished; in particular, the Shakers often replaced seating materials.

Rocking chair/production chair #6 c. 1870–75

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the World

wood, cotton, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

L2012.2701.060

Production chairs were sold by stores in Shaker communities or through mail order catalogs. Shaker brothers also took wagonloads of goods over established trade routes where they were sold directly to merchants or left to be sold on consignment.

Child’s rocking chair/production chair #1 c. 1880–1920

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the World

birch, maple, cotton webbing, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

CH2007.30.07

L2012.2701.052

Rocking chairs were originally made for the elderly or infirm in the early 1800s before they became commonplace in Shaker communities from New England to Kentucky.

Production Chairs

At Mount Lebanon, New York, thousands of chairs and footstools were produced for sale to the outside World to benefit the community. The use of power machinery facilitated the mass production of chairs and the standardization of sizes. Brother Robert Wagon (1833–83) played a pivotal role in the coordination of chair making in Mount Lebanon. He developed a numbering system according to chair size. Zero represented the smallest child’s chair and number seven, the largest adult chair. The number was typically stamped on the back of the upper slat. In the early 1870s, illustrated catalogs were published in order to advertise production chairs. Shaker chair making was further popularized following the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. The Shakers exhibited a display booth at the Exposition and were awarded a medal for their chairs. Shaker chairs were sold as far west as Chicago and were imitated by many worldly manufacturers. By the early 1900s, as Shaker communities grew smaller, chair production began to steadily decline.

Table c. 1840–50

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community

pine, cherry, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

TA2007.01.07

L2012.2701.048

Woodwork

Many skilled woodworkers joined Shaker communities. Their furniture quickly became known for its remarkable precision and painstaking workmanship. Shaker furniture makers and workshops paralleled their worldly counterparts. Historically, carpenters were responsible for building construction. Joiners crafted furniture that required fastening wood parts together with various joints such as mortise-and-tenon and dovetails. Turners, commonly associated with chair production, operated lathes for turning wood to make columned shapes such as chair legs. Woodworkers used hand tools to make furniture until machinery, such as circular saws, were introduced in the second half of the nineteenth century. Even so, craftsmen finished much of their work by hand.

In the first half of the 1800s, the growth of communities created the need to furnish dwellings with chairs, beds, stands, chests, and other basic items. Shaker woodworkers also concentrated on building specialized forms to suit their community’s needs. Living and working in large communal families required furniture designed for groups rather than individuals. Long work counters, benches, dining tables, large cupboards and built-in storage units were some of the more common forms of communal furniture produced in Shaker communities.

Oval boxes c. 1835–50

Canterbury, New Hampshire, or Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community or the World

wood, stain, metal

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

BX2007.12.02, BX2007.13.02, BX2007.27.07, BX2007.33.07, BX2007.38.07

L2012.2701.002a,b, L2012.2701.009a,b, L2012.2701.003a,b, L2012.2701.001a,b, L2012.2701.005a,b

Oval Boxes

The oval box, a quintessential Shaker form, had a long history in Europe and America prior to its popularity as a Shaker-made good. The Shakers, however, did perfect the form, producing boxes with uniformly slender sides, symmetrical joints, and tight-fitting lids. The oval shape may have partially developed for economical reasons. A twelve-inch circular box must be made from a twelve-inch board, but a twelve-inch oval box can be made from a nine-inch wide board. The Shakers first began to make oval boxes at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Early boxes were made using hand tools; later on, the Shakers used circular saws to cut the sides, rims, tops, and bottoms of the boxes. The sides and rims were usually made of maple and the bottoms and tops of quarter-sawn pine. Pieces were soaked in hot water or steamed until they became pliable and could be shaped around a wooden mold. Boxes were made in graduated sizes. Around 1833, sizes were standardized and numbered; eleven, the smallest number, sold for three dollars a dozen or twenty-five cents a piece. The largest, number one, sold for nine dollars a dozen or seventy-five cents each.

Blanket chest c. 1840

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community

pine, stain, bone escutcheons

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

CS2007.02.07

L2012.2701.019

Mount Lebanon, New York

Following the death of the founder of the Shakers, Mother Ann Lee, in 1784, Father James Whittaker (1751–87) established the Mount Lebanon Shaker Community in New York. Under Whittaker’s leadership, and later under the administration of Joseph Meacham (1742–96) and Lucy Wright (1760–1821), Mount Lebanon became the premiere spiritual and industrial center and served as a model for all other Shaker communities to follow. During its most prosperous years, six hundred members built hundreds of buildings on more than six thousand acres of land. Mount Lebanon’s buildings also served as architectural models for other societies. The first meeting house, built in 1785, was not only the first building at Mount Lebanon, but also the first Shaker meeting house in North America.

The community was originally referred to as New Lebanon due to the close proximity of the town of New Lebanon. In 1861, the Federal government officially recognized the community as “Mount Lebanon” and allowed the Shakers an independent post office. The Mount Lebanon community specialized in chair making and manufactured more chairs for sale to the World than any other Shaker village. The community remained active until 1947.

Work stand c. 1840

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community

cherry, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

ST2007.02.07

L2012.2701.026

Tripod Tables

The Shakers crafted a number of tripod tables from work stands to sewing stands. The earliest Shaker stands date from about 1805. Typically stands have round, square, or rectangular tops and peg-, snake-, or spider-shaped legs. Spider-shaped legs were among the most popular and common styles. Craftsmen borrowed from contemporary worldly models for the form of their tripod stands. The snake-shape legs found on many candle stands derive from the Queen Anne style. Tripod tables were commonly found in rooms and halls, where they may have been used for small sewing projects and other tasks.

Tripod stands and other furnishings were made from a variety of woods. Pine, which was readily available to the Shakers, was commonly used. Depending upon local availability, cherry, maple, walnut, and other woods were also employed. Many pieces, such as writing desks, were made from more than one type of wood. Furniture parts that required a great deal of strength, such as bedposts, were often constructed from sugar maple. Woodworkers usually used hardwoods for table legs and rails to provide strength to the mortise-and-tenon joints.

Sewing stand c. 1840

Enfield, Connecticut

made for the Community

pine, maple, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

ST2007.01.03

L2012.2701.025

Textiles

Shaker women were responsible for the majority of textile work from spinning, weaving, dyeing, sewing, and knitting to mending, darning, washing, and ironing. Communities raised sheep for wool and grew flax to make linen. Shaker brothers in many communities constructed spinning wheels for community use and for sale. Sisters made many of their own textiles, such as clothing and bed linens. Fiber processing and cloth production was done by hand until mechanization was developed. For instance, a Shaker community might have continued to raise sheep, but sent their wool out to nearby carding and spinning mills when they began operation. The Shakers also purchased a great deal of cloth from the outside World. In 1824, in Sabbathday Lake, Maine, community members invented a method of making cloth wrinkle-resistant. They treated cotton or wool fabric with a zinc chloride solution, then pressed and applied heat to the fabric.

Sewing box c. 1900–20

Sabbathday Lake, Maine

made for the World

pine, maple, fabric, copper nails, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

BX2007.18.10

L2012.2701.012

Sewing box c. 1840, converted to sewing box c. 1900

Mount Lebanon, New York

originally made for the Community, later sold to the World

pine, maple, fabric, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

BX2007.20.07

L2012.2701.013

Originally made as an oval box in the 1840s, around 1900, a Shaker craftsman converted this sewing box into its present form. In the early 1900s, many items originally intended for the community were converted to fancy goods and sold to the outside World.

Fancy Goods

Shakers lived separate from the outside World, but they were still affected by it, and their communities changed and adapted over time due to both external and internal influences. As the Industrial Revolution progressed in the late 1800s, agriculturally-based activities and sales became more difficult to sustain. At the same time, Shaker populations began to dwindle, and there was a significant decrease in male membership. The Shakers, however, still relied on sales from the outside World to help support their communities.

In order to supplement their income, many Shaker women in northeastern communities began making “fancy goods” for sale. In previous decades, the Millennial Laws had prohibited the making of fancy articles with ornaments and trims. Although fancy goods differed from products sold during the pre-Civil War period, the quality of the articles remained exceptional. Items such as sewing boxes embellished with a number of satin bows, pincushions, and spool holders were sold at Shaker stores, country fairs, and resort areas. These items were particularly popular with tourists who desired trinkets and souvenirs during their visits to various places in New York, New England, and the nearby Shaker villages.

Spool holder with pincushion c. 1910

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the World

maple, fabric, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

MS2007.47.07

L2012.2701.039.01-07

Cat’s head basket c. 1886

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community

black ash, copper nails

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

MS2007.11.07

L2012.2701.028

The initials “A.C.W.” are carved on the handle of this basket in cursive lettering and dated 1886.

Basketry

Shaker basket makers perfected traditional forms and techniques already being produced in the northeastern United States. Early basket handles were carved by hand and shaped with drawknives and files. Later, mechanical saws and routers were used to refine and standardize shapes. Labor-intensive basket making entailed pounding a log to separate the fibers so that the long strips needed for weaving could be peeled away. The Shakers made baskets from ash, a wood that can be easily split and bent. Basket makers made wooden molds to guarantee perfectly formed baskets, uniform in size, volume, and shape. Baskets were made for sale and for use among Shaker communities. Although every Shaker community crafted baskets, the Mount Lebanon community is best known for producing large quantities of basketry. There, the Shakers made approximately 70,000 baskets during a sixty-year period. Originally, both males and females participated in the manufacture and sale of basketry. When the male Shaker population began to decline in the late 1800s, women became solely responsible for basketry production.

Chopping bowl c. 1840

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community

birch, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

L2012.2701.063

Food and Dining

Shaker food was simple, hearty, and healthy, always utilizing domestically grown ingredients. The members of each Shaker family ate three daily meals together in large dining rooms inside their dwelling house. Brothers and sisters sat on opposite sides of the room eating with minimal conversation. Preparing meals for communal families of up to one hundred members required a great deal of labor. Sisters in each family shared the responsibility by rotating kitchen duties for an average period of four weeks at a time. The Shakers, who embraced new technology, featured modern cook stoves in their kitchens as they became available. Oversized bowls, such as this one made from a single piece of wood, made it easier to prepare dishes for large groups. For instance, a squash biscuit recipe might require sixteen cups of flour, six cups of squash, three cups of milk, and three cups of sugar.

Six-drawer chest c. 1840Watervliet, New York

made for the Community

pine, cherry, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

CS2007.06.15

L2012.2701.044

Shaker Order

Many Shaker villages were founded on land donated by new followers. Those curious about potentially joining a Shaker community would have visited the trustees’ office where any of their questions would be answered. Or if it was a Sunday, they might be invited to attend a church service at the meeting house. In many cases, married couples joined Shaker societies, although they relinquished living together as man and wife. Not all Shakers remained committed for a lifetime: many left or longed for the outside World after spending months, several years, or even decades in Shaker villages.

Communities varied in size, but at the height of the Shaker movement, villages might have had anywhere from two hundred to eight hundred people. Communities were divided into families of up to one hundred people, and families were further organized by degree, be it novitiate, junior, or senior. The number of orders and families varied according to the community, but there was always a Church Family where the most trusted and respected members lived, including the spiritual leaders and trustees, who handled legal, financial, and business matters, and deacons who handled domestic matters. Additional families were named according to their geographic location from the meeting house, such as North and South Families. Two appointed male elders and two female elders, who often served a life-long term, oversaw each family. Each group lived in their own dwelling house and was responsible for certain buildings, workshops, and day-to-day tasks, which were further divided by gender.

Stool c. 1850

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the Community

maple, rushes, paint

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

ST2007.07.07

L2012.2701.022

Shaker Finishes

Throughout their history, the Shakers applied paint, stain, and varnish in various combinations to furniture. These coatings not only enhanced the pieces aesthetically, but also increased their longevity. Many early furnishings were covered with opaque coats of paint. In the late 1700s, when communities first began making furniture, until after the Civil War, ready-made paint was unavailable to Shaker craftsmen and their worldly counterparts. Various pigments and oils had to be laboriously mixed and ground by hand. The Shakers purchased many of their paint components from outside sources.

During the 1830s, craftsmen began to thin the paint so it resembled a stain rather than a heavy opaque coating. This clever technique enabled the fine wood grain to show through. Varnishes with a light hue also began to be applied in the 1830s. Typically, a paint or wash was applied to a piece of furniture, followed by a clear coat of varnish. This final coat protected the initial finish and in some cases added a glossy sheen. Because furniture was often refinished to keep it looking its best, many Shaker pieces have several coats of varnish or paint.

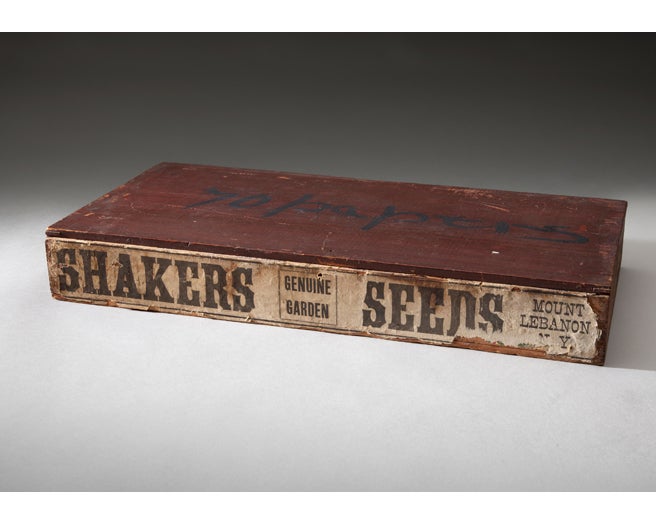

Seed box c. 1880–90

Mount Lebanon, New York

made for the World

pine, paper, metal brads, stain

Collection of Benjamin Rose, San Francisco, California

BX2007.47.07

L2012.2701.042

The Shaker Garden Seed Industry

The Shakers developed a garden seed industry by the turn of the nineteenth century. Like all of their products, their seeds were always of the highest quality. By the early 1800s, Shaker garden seeds were widely regarded as the best available in the eastern United States. Their early success was also due to the fact that they were among the first to offer garden seeds for sale during a time of great demand, when large numbers of settlers began obtaining plots of land to farm. Prior to the seed industry, people gathered seeds from their own crops each year and traded seeds locally.

The entrepreneurial Shakers originated the idea of selling seeds in paper packets and invented machinery to cut, fold, paste, and print the bags in their own shops, in addition to offering printed seed catalogs. Shaker seed boxes became a staple in general stores, where shop owners typically received a one-third commission. A typical seed box held about two hundred seed packets, selling for five to six cents each. By the 1830s, various Shaker communities offered seventy kinds of seeds, such as melon, onion, parsley, parsnip, beans, and cabbage. The Shakers first offered tomato seeds in 1835, when the fruit, which originates from Central and South America, was still a novelty to North American settlers.