International Terminal

Cap back late 1700s

Point de Venise à Réseau needle lace

Italy

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JAC12357

L2013.3501.013

The exquisite cap back displays some of the finest needlework ever produced. With a count of 10,000 stitches per square inch, it represents five years worth of work. Needle lace evolved from fifteenth-century cutwork embroidery, in which designs were cut out of a woven cloth, their edges secured with threads that provided a decorative element. Nearly a century later, the fabric itself would be eliminated, the needle and thread alone forming lace. Astonishingly, an entire fabric was now created stitch-by-stitch using a single needle and thread. The first true needle lace appeared in Venice, Italy, in the mid-1500s and was aptly called Punto in Aria (points or stitches in the air).

Needle lace tends to be firmer and crisper in appearance than woven bobbin lace. To make needle lace, foundation threads are basted along the outlines of the design, through the parchment pattern, and under a layer of cloth. Design motifs are then created with rows of buttonhole stiches, with additional decorative elements such as picots or ornamental loops added. The finished motifs are then joined by decorative bars or a needle-made mesh (reseau) background. Once complete, the basting stitches are removed, releasing the lace.

Traditionally, lace makers who produced fine needle and bobbin lace learned the craft in childhood from relatives, at lace schools, or in convents. The best lace makers demonstrated astonishing skill. Their eyes had to be sharp and their hands sensitive to the gossamer-fine thread used to make high-quality lace.

Edging 1800s

Point de Paris, straight bobbin lace

Belgium

Collection of The Lace Museum, Sunnyvale, CA

1997.0433.002

L2013.3503.003

Lappet early 1700s

Binche, straight bobbin lace

Collection of The Lace Museum, Sunnyvale, CA

1992.0102.161

L2013.3503.001

Bobbin lace, which tends to have a softer look than needle lace, evolved from the techniques applied to make various passementerie such as braids and trimmings, which embellished clothing and furnishings. Bobbin lace is made by plaiting a number of threads using a small bobbin on one end that serves as a handle to control the thread, while the other end is secured to a firm pillow. The lace is worked over a parchment pattern (pricking). The stitches are guided with pins placed in pre-pricked holes in the pattern. In straight bobbin lace, all threads work through the entire piece, forming both the ground and motifs, each thread supported by a bobbin. The most complex pieces require over one thousand bobbins.

The lace at bottom is named Binche after the small town in the north of France near the Belgian border where it may have originated. First made in the 1600s, it is considered some of the finest bobbin lace ever produced, made with a snowflake-like background and stylized flowers.

Shawl mid-1800s

Blonde bobbin lace

France

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JTB15433

L2013.3501.052

Blonde bobbin lace made from fine silk thread was first made in the mid-1700s. By the early 1800s, Chantilly and Caen, both in Northern France, produced some of the finest Blonde lace. Admired for its delicacy and glossy luster, it was referred to as Blonde due to its honey color, although it was also made in black. By the 1810s and 1820s, Blonde lace had become so popular that it was used for flounces, stoles, veils and entire dresses. Around 1840, the desire for Blonde lace declined, and fashionable women instead chose to wear Chantilly lace. Both Blonde and Chantilly laces remained desirable in Spain long after their popularity had waned elsewhere.

Fan leaf mid-1800s

Chantilly bobbin lace

France

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JPB12753

L2013.3501.071

Unlike Blonde lace, Chantilly bobbin lace, typically black, was made with a dull, rather than shiny, silk thread and the woven floral arrangements more realistically depicted. Chantilly, which received its name from one of the towns it was made in, remained popular until the end of the century. Chantilly was popular at a time when large black shawls, veils, mantillas, fans, and lappets were important components in formal dress. By the mid-1800s, machine lace that often superbly imitated Chantilly assured the permanent decline of the handmade version during the 1870s.

Pictorial scene late 1800s

Brussels, free bobbin lace

Belgium

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JVB.12423

L2013.3501.001

There are three types of bobbin lace construction: straight (continuous), free (non-continuous) and tape (continuous ribbon). Free bobbin lace entails making individual motifs, such as flowers, with the threads following the shape of the designs. These motifs are supported by short joining bars or a mesh ground (reseau). Free bobbin lace facilitated speedier production, as many lace makers could contribute to a single piece.

Fan late 1800s

Brussels bobbin lace

France

Collection of The Lace Museum, Sunnyvale, CA

1994.0433.236a

L2013.3503.031a

The folding fan originated in Japan; it was introduced to Europe in the second half of the sixteenth century. The European version was constructed in a similar fashion, but with Western decoration. Painted or lace-embellished fans were common. A fan was an essential fashion accessory in the formal dress of a wealthy woman and helped cool a lady’s face. The fan was also used as a subtle tool for flirting with suitors. Allegedly, during the Victorian Era, a language of the fan developed. For instance, drawing the fan across the cheek meant, “I love you,” while fanning slowly signified, “I am married.” Placing the fan on the right ear meant, “you have changed.” It is dubious, however, that the language of the fan was a serious code for communication. It most likely developed as a clever advertising scheme by those selling fans and other fashionable accessories, such as parasols and handkerchiefs.

Flounce fragment c. 1890

Arts and Crafts-inspired Point de Gaze needle lace

Belgium

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JTC12355

L2013.3501.007

Lace manufacturers constantly attempted to make beautiful lace more quickly and less costly than that of previous generations. Perhaps no other handmade lace met this goal as well as Belgian Point de Gaze, which first debuted at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. With its introduction, Belgium, long known for its outstanding bobbin laces, became a preeminent center for needle lace in Europe. Point de Gaze was one of the last of the great, entirely handmade laces developed and offered commercially. It resembled Point de Alençon, one of the finest of the French needle laces of the eighteenth century, but with a much simpler structure. The result was a lighter, delicate lace that was quicker to execute, encouraging a new freedom of design and a variety of novelty creative stitches. Point de Gaze incorporated naturalistic forms, such as sprays of flowers, occasionally with separate layers of rose petals individually sewn on to create a three- dimensional effect. It was a popular bridal lace well into the twentieth century.

Bodice c. 1900

Bruges bobbin lace

Belgium

Collection of The Lace Museum, Sunnyvale, CA

1994.0433.002

L2013.3503.025

Since its inception, both men and women wore collars and cuffs made from lace. By the 1800s, men no longer wore lace, but women continued to wear lace collars and cuffs in a variety of styles. Bruges lace trims the collar and cuffs of this Edwardian bodice. This type of lace was made from the mid-1800s to early 1900s in Belgium with a coarser thread and larger motifs than earlier bobbin laces, such as Brussels. The boldly patterned lace could be made fairly quickly. Rather than displaying a mesh ground, separate flowers and other motifs were made individually and joined together by picot-edged cords or bars. Commonly exported to the United States, this reasonably priced lace allowed a broader market to purchase handmade lace.

Dress front late 1800s

bobbin lace

M. Jesurum & Co.

Pellestrina, Italy

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JAB12353

L2013.3501.003

The Italian lace manufacturer M. Jesurum & Co. established a lace school on the island of Pellestrina, Italy, in the 1870s. Students made lace in a range of historical and innovative styles, such as this multi-colored silk bobbin lace bodice front.

Edgings late 1800s–early 1900s

metallic gold bobbin lace

France

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JTB23789

L2013.3501.057, JTB23779, JTB23791, JTB23775

L2013.3501.057, 058, .059, .095

Gold, silver, and other metallic threads were long used for various trimmings and ornamentation prior to the manufacture of lace, so it is no surprise that metallic lace developed sometime in late 1500s. The luxury item trimmed skirts, gloves edgings, and adorned jackets. Metallic lace was sold by weight because of the high gold and silver content. Monarchs such as Queen Elizabeth I wore metallic bobbin lace. In fact, it was worn in such quantities in England and France that sumptuary or regulatory laws were enacted to restrict its importation, creation, and use.

Typically, metallic threads were made by twisting fine metallic strips around a silk thread. Silver plated with gold was commonly used rather than pure gold. The coarseness of metallic threads were well-suited to the plaiting technique of bobbin lace. The lace never achieved the suppleness of linen lace because it was impossible to twist and bend the stiffer threads as closely as linen. Today, not much remains of early metallic lace because it was melted down to recover the precious metal.

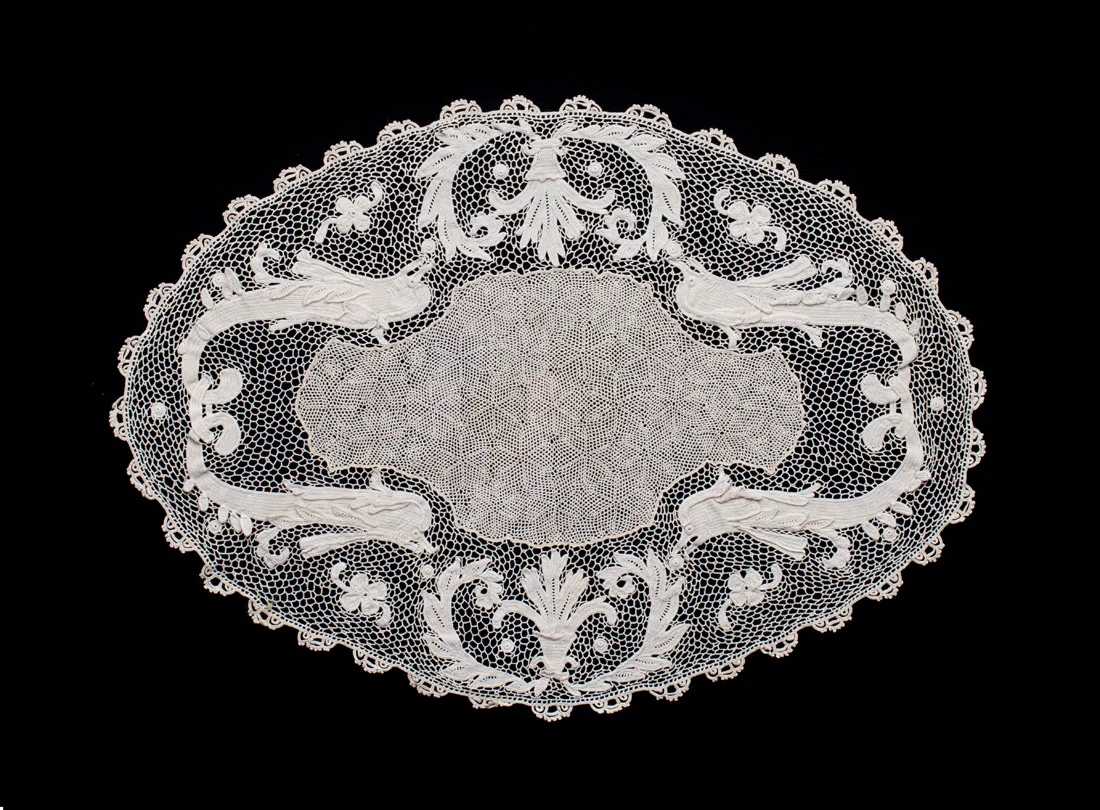

Doily with dolphin theme early 1900s

crochet lace

Orvieto, Italy

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JHE29502

L2013.3501.040

Like knitting, crochet is a single thread technique worked in the hand, but with a hooked needle rather than knitting needles. Crochet is the French word for “hook,” the tool used to make the lace. It may have developed in France during the seventeenth century. When worked with the finest threads and hooks, such as the cut eye of a needle, it is difficult to distinguish from needle lace. Crochet lace became popular in the 1800s. Nineteenth-century design books often printed only a drawing or picture, which clever homemakers could copy without detailed instruction. Lace makers in Orvieto, Italy, made outstanding crochet lace at the turn of the twentieth century. First inspired by Irish crochet, lace from this area soon developed its own unique style.

Dress 1920s

tape lace

United States

Collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles, Berkeley, CA

JDA20247

L2013.3501.037

Tape or Battenberg lace is constructed mainly of cloth-work tapes. Tapes are secured to a design on a pattern and filled in with decorative needlework. Because tape covered far more area than thread, it provided a less expensive lace option. Tape lace was produced as early as the seventeenth century when the narrow tapes were made by a simple bobbin lace technique and the spaces between the looped tape filled in with needle lace stitches. Tape lace was revived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By the late 1800s, manufacturers produced a variety of machine-made tapes in different widths, sometimes with picots or other decoration. Tape lace also became a popular bridal lace and was referred to as “Princess” lace. Battenberg was originally a term for specific type of tape lace with elaborate needle stitches, but later became a generic name for the lace after Princess Beatrice of England married Prince Henry of Battenberg in 1885.