International Terminal

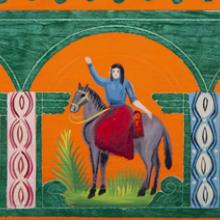

Model ox cart and figure c. 1958

attributed to the Mixtec Indians

Arrazola or San Martín Tilcajete, Oaxaca, Mexico

wood, paint, metal

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–15719a-e

L2011.0701.030a-e

The Oaxaca Valley is in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. Many people from the area are descendants of the Zapotec Indians, native to the region. This ox cart, a common sight in rural Mexico, is an early example of Oaxacan wood carving, which first developed in the 1940s with wooden dolls made for local markets. By the 1960s, renowned carver Manuel Jiménez began creating imaginative figures and creatures of all kinds from copal, eaglewood, and cedar. Oaxacan wood carving has evolved over the decades. Today, the painting styles are embellished with intricate patterns and motifs and air-brushed rather than simplistically painted.

Three-tiered building c. 1960s–70s

Jalisco, Mexico

clay, paint

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–30454

L2011.0701.157

Candelario Medrano (1918–1986), a famous ceramicist of figural scenes, hailed from Santa Cruz de las Huertas in the state of Jalisco, one of the largest pottery-producing states in Mexico. Medrano, like many others in his village, produced clay sewer pipes for years before he began crafting his playful creations. Julio Acero, a toy maker from the same village, first introduced Medrano to clay sculpture. Medrano is known for his brightly painted, whimsical buildings, animals, cars, planes, and fantastical spaceships. Animated figures that hang out of windows, play musical instruments, or operate vehicles populate many of his pieces. Medrano’s children and grandchildren have continued his legacy.

Box c. 1950s

Javencio Ayala e Niños

Olinalá, Guerrero, Mexico

wood, lacquer

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–15739

L2011.0701.032

Lacquerware was produced in Mesoamerica long before the Spanish arrived. Lacquer, a glossy coating, serves to waterproof and decorate wood and other organic materials such as gourds. In a laborious process, the surface is smeared with seed or insect oils and then covered with several coats of powdered minerals, which are repeatedly dried and polished before being painted.

Lacquer is presently created in three regions: Michoacán, Guerrero, and Chiapas. The decoration is applied by painting, incising, or inlaying. All three regions produce painted wares (aplicado or dorado), but inlaid ware (embutido) is crafted only in Michoacán, while incising or carving (rayado) is limited to Guerrero. For inlaid pieces, a design is first laid down, and then parts of the pattern are cut out and the hollows filled in with another color. For the carved technique, two coats of contrasting colors are applied and the top coat is scraped away to create the design. For painting, designs are simply painted with oil pigments onto the lacquer surface.

Female figurine c. 1960s

San Agustin, Oapan, Guerrero, Mexico

clay, paint

Collections of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3-23029

L2011.0701.065

Large ceramic dolls were once produced in San Agustin, Oapan, and Amayaltepec in the state of Guerrero. The dolls are painted with naturalistic designs against a cream-colored background. The painting style inspired the bark paintings or amate now a common folk craft in the region. Potters simply began painting the same motifs onto bark paper that they had long painted on clay. Others who had never worked in clay recreated the designs on bark paper. No longer common, this natural style of painting on clay has been replaced by bright colors and high-gloss coatings.

Ram figurine c. early 1940s

Veracruz, Mexico

clay, paint

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–14737

L2011.0701.018

Mold-made, ram figurines made of clay in the form of banks are now a rarity. Similar figures made out of sugar paste are placed on Day of the Dead altars. Day of the Dead (Dia de los Muertos), one of the most important holidays in Mexico, honors deceased loved ones. On this day, it is said that the souls of the dead return to visit their families. The souls are welcomed into homes where altars decorated with special foods, candles, and incense are displayed.

Dressed fleas before 1957

Guanajuato, Mexico

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–28931a,b

L2011.0701.125a,b

This pair of fleas is dressed in male and female clothing; occasionally, artisans grouped fleas into scenes like weddings.

Bird vessel c. 1950s

Acatlán, Puebla, Mexico

clay

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–15868

L2011.0701.053

Although blackware has been produced in Oaxaca since pre-Columbian times, this distinctive Coyótepec style was developed in the 1950s. The surface of the pottery is burnished with a quartz burnishing stone before being fired. The rich, black color is achieved during the firing. The potter quickly seals all openings to the kiln, producing thick smoke that permeates the pieces with carbon. When the pieces are removed, they are polished with animal fat, wax, or oil, which protects the pottery while producing a lustrous coating.

San Bártolo Coyótepec is approximately twenty minutes from the city of Oaxaca. One of its former residents, Doña Rosa, was renowned for the beautiful forms she created and her expert ability in burnishing each piece. This resulted in a brilliant and intense black surface after the pottery was fired. Her “potter’s wheel,” on which she formed her clay, consisted of two gray ceramic saucers placed back to back, an indigenous method. A molde or circular dish is used as a base to shape the clay. It balances and rotates on the volteador of a similar shape; sometimes consisting simply of a flipped-over bowl. Many of Rosa’s family members continue to craft blackware in the same manner.

Female figurine c. 1950s–60s

Oaxaca, Mexico

Clay

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–30418

L2011.0701.153

Influential folk artist Teodora Blanco (1928–1980) first began crafting her innovative clay figures as a teenager when she made animal musicians. In her late twenties, she shifted her focus to the imaginative female figurines for which she is best known. Oaxacan clay water-coolers inspired the basic form of her figures. Blanco’s pieces, however, crafted solely as decorative sculptures, ceased to retain their utilitarian function. Her lively figures show women holding animals, children, and market baskets. Rather than painting her pieces, she applied surface decoration through clay appliqué, the most striking aspect of her work.

Candelabra before 1958

Puebla, Mexico

clay, paint

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3-15746

L2011.0701.033

The tree of life candelabra, a popular form of Mexican folk art, symbolizes fertility and rebirth. People often place these decorative objects in their homes or use them at church ceremonies, weddings, and funerals. Crafted in great detail, trees display figures such as people, skeletons, flowers, fruit, and birds. Trees of life may take weeks to complete. First, the base of the tree is formed; then, branches are crafted from coils of clay. Artisans typically create the ornamentation for these candelabra using press molds. Molds are often passed down from generation to generation. A common method of ceramic construction in pre-Hispanic Mexico, press molding allows artisans to produce multiples of the same form using molds. Once the clay has dried, the trees are fired and then painted.

Spaceship with mariachi band c. 1960s–70s

Jalisco, Mexico

clay, paint

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

JP–1

L2011.0701.161

Candelario Medrano (1918–1986), a famous ceramicist of figural scenes was from Santa Cruz de las Huertas in the state of Jalisco, one of the largest pottery-producing states in Mexico. Medrano, like many others in his village, produced clay sewer pipes for years before he began crafting his playful creations. Julio Acero, a toy maker from the same village, first introduced Medrano to clay sculpture. Medrano is known for his brightly painted, whimsical buildings, animals, cars, planes, and fantastical spaceships. Animated figures that hang out of windows, play musical instruments, or operate vehicles populate many of his pieces. Medrano’s children and grandchildren have continued his legacy.

Chocolate jar probably 1700s

Puebla, Mexico

clay, glaze, metal

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–29585a,b

L2011.0701.148a,b

In Mexico, such containers were commonly called chocolateros or chocolate jars, because they were used to store delicacies such as spices, chocolate, vanilla, or wine.

Carved gourd c. 1890–1910

Oaxaca, Mexico

Collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

3–29443

L2011.0701.141

Natural containers used for thousands of years in Mexico, carved gourds and coconuts are a unique form of Mexican folk art. Some simple gourds serve as bowls and utensils, while others are transformed into rattles or intricately carved decorative objects. In parts of Oaxaca, Mixtec Indians carve ornamental gourds. Artisans in Tabasco and Veracruz carve coconut shells and other large seeds in a similar fashion. Prisoners once commonly carved gourds and coconuts to sell.

Craftspeople carve gourd bowls from the rind of the fruit of the calabash tree (Crescentia cujete), which grows in the coastal areas of Guerrero and Oaxaca. Gourds are left to dry and then cut in half and placed in water until the interior rots. The hard rind is then cleaned out and smoothed before being carved, polished, and sometimes painted or lacquered.