International Terminal

Simple microscope with case 1673–1748

Samuel (1640–81) and Johan Joosten van Musschenbroek (1660–1707), Holland

brass, wood, leather, gilt, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

097

L2011.2301.004

In the late-seventeenth century, the workshop of Samuel and Johan Joosten van Musschenbroek provided a rich selection of instruments to the scientific community, including Jan Swammerdam (1637–80), who famously used a Musschenbroek magnifier to study the nervous system of insects. This first version of their simple microscope has three of its six original objectives—the lens closest to the sample. These objectives consist of biconvex lenses mounted in turned hardwood holders and placed on the end of the tapered brass rod. A series of articulated ball-and-socket joints, known as "Musschenbroek nuts," connects the objectives to one of several specimen holders. The magnifier and accessories are contained in an oval case stamped with the Musschenbroeks' symbols—an oriental lamp and a pair of crossed keys.

Tripod microscope c. 1660

probably Italy

ivory, wood, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

253

L2011.2301.011

This early compound microscope features a body made from several pieces of turned ivory threaded together and is supported on three mahogany pillars. An eye-lens is mounted at the top end, with a threaded hardwood peg that can be screwed into the hole for use as a dust cover. The bottom end of the body features a hardwood nosepiece into which an objective lens is mounted. The microscope has no field lens (a positive lens placed between the objective and the eyepiece lens), signifying that it was likely made prior to 1664. There is no provision for transmitted light, so illumination of the examined sample is by reflected light only. The base is a circular piece of turned ivory, with a peg at the center acting as a sample stage.

Great Double Microscope 1710

John Marshall (1663–1725), London

wood, brass, cardboard, leather, gilt

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

117

L2011.2301.015

John Marshall was one of the most important opticians and microscope makers of the seventeenth century. Marshall's Great Double Microscope was inspired by the large compound microscope used by Robert Hooke and illustrated in his publication Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses (1665). The microscope's name was intended to reflect the instrument's large size and the fact that it was a compound microscope. Marshall's microscope features a number of valuable contributions to the field of microscopy—a rigid supporting pillar that holds the specimen stage, a ball-and-socket joint at the base to incline the microscope, and the incorporation of a fine-pitch thumbscrew device that was previously used to adjust the focus of telescopes. Other advances include a base-mounted condensing lens for transparent objects and a graduated set of objectives. Interestingly, Marshall's contemporary, Edmund Culpeper (c. 1660–1 740), later modified this microscope with an additional lens at the top and a reflecting mirror.

Screw-barrel microscope with compound attachment and reflecting mirror c. 1720

Edmund Culpeper (c. 1660–1738), London

brass, ivory, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

071

L2011.2301.007a,b

Edmund Culpeper was one of the most famous microscope makers of the early eighteenth century. Culpeper's screw-barrel simple microscope with ivory compound attachment is supported on a tripod stand. An articulated arm with lens extends from the central rod of the stand. The compound attachment consists of the body with an attached, threaded collar and low-magnification lens; and an internal ivory drawtube with eye lens. This compound-lens system threads into the screw-barrel component, which then acts as a sample holder. With the compound assembly removed, an objective lens can be screwed into the brass body making the system a conventional, simple magnifier. Five of the six original objective lenses remain.

Double-Reflecting Microscope with case c. 1730

Edmund Culpeper (c. 1660–1738), London

brass, ivory, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

181

L2011.2301.016

The tripod, in use since the beginning of the sixteenth century to support spheres and globes, was one of the first forms used for mounting microscopes. Early versions featured an aperture in the center of the base, with the instrument placed over a glass plate covering a hole in a table. A candle placed beneath the table would illuminate a transparent specimen. Edmund Culpeper's important contribution in the late 1720s was to design the bottom part of his instrument to perform this function and to incorporate a concave mirror in the optic axis to act as both the instrument's reflector and condenser. Culpeper's Double-Reflecting Microscope features two platforms, each supported by three turned brass pillars. Although the first design had wooden platforms, he quickly switched to brass. The microscope body's cardboard tube is covered in green-dyed vellum. It fits within an outer tube covered with ray skin, and is pushed up or down to achieve focus with friction maintaining the desired position.

Culpeper's instrument came in a pyramidal oak case with accessory drawer that includes brass forceps, "fish plate" for live specimens, black/white contrasting disc, and objective lenses in turned dark wood, protected by leather sleeves. Culpeper's trade card, affixed to the back interior of the cabinet, features the maker's crossed-daggers logo and a variety of instruments he produced— globes, sextants, sundials, quadrants, spectacles, and screw-barrel microscopes. The Culpeper-style compound microscope, attractive and relatively inexpensive to make, remained in production through the end of the eighteenth century. It was particularly popular with amateur users during the Victorian era who employed the instrument for amusement as well as scientific investigation.

Dissecting simple microscope c. 1750

Johan Georg Mitsdörffer, Berlin; after Johann Nathanael Lieberkühn (1711–56)

brass, ivory, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

142

L2011.2301.019

Johan Georg Mitsdörffer's large dissecting microscope was based on a form developed by Berlin physician Johann Lieberkühn in the first half of the eighteenth century. Lieberkühn dubbed this instrument an "anatomical microscope," but it is better described as a blood circulation microscope as it was used for studying the membranes and circulation of blood in small animals. The microscope employed a thin sheet of brass formed in the shape of an animal figure, with ten sliding hooks positioned around its perimeter. Four larger hooks at the corners were designed to hold the legs of the live subject, while the smaller hooks were used to pull back successive layers of membrane opposite the lens for examining its tissue and circulation. To achieve focus, a thumbscrew adjusted the pliable band to which the lens was secured. This microscope required strategic placement before a window or lamp for light to pass through the examined material.

Compound microscope c. 1745

John Cuff (1708–72), London

brass, wood, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

018

L2011.2301.024

John Cuff was an important contributor to the field of optical instruments in the mid-eighteenth century. In 1744, frustrated in his attempts to modify a Culpeper microscope with a focusing device in the top of its snout, and after referring to the addition of a Lieberkühn reflector (a concave reflecting mirror to illuminate opaque objects), Cuff wrote: "But the legs I could not get rid of, nor was it possible in that form to make the whole fully answer the desires of the curious. In order, therefore, to remove all complaints the present microscope is contrived on a new construction whose motion is easy and regular and steady; whose application for opaque and all other objects will be found convenient; whose stage is quite free from any object to be applied on; and whose general figure cannot, it is hoped, be thought unhandsome."

Cuff abandoned the tripod stand and tube-in-tube focusing mechanism used in popular Culpeper-style instruments. Cuff's design employed the fine-adjustment thumbscrew introduced on telescopes by Johannes Hevelius (1611–87) nearly a century earlier and famously used on John Marshall's Great Double Microscope. Cuff improved on the optics and focusing pitch of earlier microscopes, and his design features greater accessibility than three-pillared instruments—allowing the observer to more easily manipulate the specimen by hand. Hand-engraved indicators are used for positioning the illuminated light reflector (now missing) according to each of its six objective lenses. The drawer in the base of the instrument contains extra objectives, a case for the Lieberkühn reflector, and an aquatic slide for examining pond water.

New Universal Microscope c. 1746

George Adams, Sr. (1709–72), London

brass, ivory, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

282 L2011.2301.029

George Adams, Sr.'s New Universal Microscope, introduced in his 1746 publication Micrographia Illustrata, or, The Knowledge of the Microscope Explain'd, is a rare and interesting example of the rapid changes in the microscope's mechanical construction during the middle of the eighteenth century. Below the instrument's brown-stained, turned-ivory body, a scalloped brass plate contains seven lenses, individually numbered on the surface. This is the first use of moveable lenses to allow the user to easily switch to the desired magnification in a compound microscope—a forerunner to the revolving nosepiece of later instruments. The stage is slid up and down to engraved numbers on the pillar indicating the proper positions for coarse-focusing. Fine-focus is accomplished by use of an internal screw at the pillar's base. A stage forceps or needle specimen holder can be inserted by tongue-and-groove fitting on the pillar, and a Lieberkühn reflector can be attached by threading into the top ring after removing the stage.

The Variable Microscope c. 1770

George Adams, Sr. (1709–72), London

brass, glass, ivory

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

143

L2011.2301.028

George Adams, Sr.'s Variable Microscope features a large, toothed wheel at the center of its design. The wheel is turned by an ivory-handled key, which adjusts the microscope's angle for observation. Coarse-focus adjustment is controlled by turning the circular ivory handle to move a sliding rod via rack-and-pinion mechanism, while fine-focus is controlled by a vertical screw on the opposite side. The stage attaches to a sliding block on the limb and features a hole at its center to receive a spring-mechanism for slides or vials. Each corner of the stage has a hole to insert the various clips and forceps included with this instrument. A large sub-stage mirror on an attractive scroll-shaped arm may be moved in any direction. Attached to the arm is a simple magnifying lens for observing large, opaque objects.

Chiquet box microscope 1788

Jean-Baptiste Noël Chiquet (1722–94), Paris

brass, rosewood, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

034

L2011.2301.031

Jean-Baptiste Noël Chiquet was one of the most respected microscope makers in Paris in the late eighteenth century, earning the title Ingénieur de Roi (Engineer to the King) in 1789. Chiquet’s box microscope is made in the characteristic French style. The instrument is mounted over a rosewood marquetry box that contains an inclinable, double-sided reflecting mirror and two drawers for accessories. A removable glass-paned top protects the instrument. A rotating frame allows the instrument’s body to be positioned horizontally. This is the only known surviving Chiquet instrument

Lucernal microscope c. 1798

William (1763–1831) and Samuel (1769–1859) Jones, London

mahogany, brass, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

033

L2011.2301.048

The Lucernal microscope projected an image of a specimen illuminated by lamp onto either a glass plate in the instrument or a separate screen. Lucernal microscopes were useful tools in the preparation of specimen drawings. This particular Lucernal microscope was patterned after the horizontal design from the Italian microscope maker Filippo Bonnanni (1658–1723) in the late seventeenth century. A pyramidal-shaped mahogany box serves as the microscope's body and is mounted by means of a dovetail groove on top of the larger rectangular box that stores the instrument. An observer uses the target hole assembled at the front of the instrument to align his or her eye with the optic axis.

The specimen holder features a spring mechanism to hold the sample slides, which are moved laterally on a rack-and-pinion mechanism. Focus is accomplished by turning a thumbscrew at the observer's end to control the distance of the specimen at the opposite end. The slide is illuminated by a condenser lens system—a biconvex lens closer to the specimen and a frosted lens further out to diffuse incoming light, usually from an oil lamp. Both are positioned by sliding them along a rod that extends from the pillar. An accessory drawer at the bottom of the cabinet stores two additional objective lenses and a variety of specimen slides—ebony for opaque specimens, ivory for transparent plant specimens, and two wooden holders with insect specimens.

Model No. 1 compound microscope c. 1870

Powell & Lealand (1857–1924), London

brass, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

149

L2011.2301.053

Powell & Lealand's Model No. 1, introduced in 1841, is considered one of the great masterpieces in the history of microscopy. The retail price of £200 reflected the extraordinarily high level of attention paid to every detail in both its design and assembly. The all-brass, monocular, compound microscope is quite heavy by design—to minimize vibration—and is supported by a sturdy tripod base. Cylindrical pivoting mounts, or trunnions, on the main support tube allow the instrument to tilt from vertical to fully horizontal. A double-sided mirror is supported on an articulating arm and half-gimbal. Coarse focus is accomplished by adjusting the trapezoidal support arm up or down via a rack-and-pinion mechanism, while fine-focus is controlled by using the "long lever" mechanism to move the nosepiece. A mounted parabolic reflector serves a similar function as a bull's-eye lens to illuminate the specimen from the side. Powell & Lealand's Model No. 1 was in production for more than sixty years.

Bulloch A1 Congress binocular microscope 1881

Walter H. Bulloch (1835–91), Chicago

brass, metal, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

160

L2011.2301.057

Walter Bulloch's large and heavy A1 Congress Microscope with a flat tripod base exhibits the high level of craftsmanship that made the Chicago maker's microscopes so highly regarded during the late nineteenth century. The instrument's body pivots on its center of gravity and rotates to allow the operator to smoothly and easily turn the entire microscope without moving the tripod. The instrument's reflecting mirror can rotate to a position above the sample to illuminate it from the top. A Wenham prism (now missing) was located just above the nosepiece to split the light from the objective into the two eyepieces. Binocular microscopes were desirable for their comfort and ease of use, but those instruments using Wenham prisms could only be binocular at low magnifications.

Binocular compound microscope 1914

Carl Zeiss (1816–88), Jena, Germany

brass, metal, glass

The Golub Collection, University of California, Berkeley

225

L2011.2301.061

At the turn of the twentieth century, a number of German instrument makers began producing microscopes that incorporated a variety of recent advances in optics and engineering, helping to turn the light microscope into a more practical and modern research tool. German physicist Ernst Karl Abbe (1840–1905) laid the foundation for modern microscope optics by defining the system of numerical aperture that characterized the range of angles by which an instrument can accept or emit light. Abbe formalized the concept of "light-gathering power" based on the acceptance angle of the objective and the refractive power of the medium below the objective (air, water, or oil) and, therefore, the resolving power of objective lenses. His work with German microscope maker Carl Zeiss revolutionized the microscope by incorporating high-quality lenses with a large aperture range. This resulted in very bright images that realized the highest theoretically possible resolution with no color shifts or other optical distortions.

This Carl Zeiss microscope features a black, lacquered body on a horseshoe-shaped base. The Bausch & Lomb logo, engraved on a brass plate near the top of the body and on the eyepiece barrels, reflects the American company's position as exclusive retailer for Zeiss instruments in the United States. An oval cutout, referred to as a "jug-handle base," allows for easy handling of the instrument. This instrument was designed as a monocular microscope in 1914, with a binocular eyepiece added around 1922.

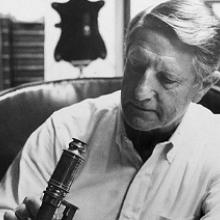

Dr. Orville J. Golub examining the Nairne and Blunt Chest microscope (c. 1760) c. 1980.

University of California, Berkeley

R2011.2301.067

The Golub Collection at the University of California, Berkeley

Dr. Orville J. Golub arrived at the University of California, Berkeley in 1937 as a graduate student and teaching assistant in the Bacteriology Department. As a Navy officer during World War II, he conducted research in the U.S. Navy Medical Research Unit #1, stationed in the Life Sciences building on campus. After the war, Dr. Golub spent two years in government service in Maryland, where he met the colleagues he would join in opening Bio-Science Laboratories in Los Angeles. In the early 1960s, Dr. Golub began collecting antique microscopes, books, and other historical items for the company museum, and later searched throughout Europe and the United States to build his personal collection. In 1995, Dr. Golub and his wife Ellina Marx Golub donated thirty-two antique microscopes from their collection to the Regents of the University of California as a gift to the Berkeley campus. Further donations from the Golubs have grown the collection to nearly two hundred extraordinary instruments, which are now on permanent display in the Onderdonk Lobby of the Valley Life Sciences Building at the University of California, Berkeley. For more information, visit golubcollection.berkely.edu